Coercive control: Impacts on children and young people in the family environment: Literature Review (2018)

Section 1: About domestic abuse and coercive and controlling behaviour

It is recognised that coercive control is a key feature of abusive relationships. It is therefore essential that the conceptualisation of coercive control and the impact it has on the whole family is recognised and understood. This review is concerned in particular with coercive and controlling behaviour within the context of public and private law proceedings. In this first section we will consider the definitions of key terms such as ‘domestic abuse’ and ‘coercive control’ and seek to contextualise them before discussing the impact they have on the family and legal proceedings. This section covers:

- Defining domestic abuse

- Defining coercive control

- Prevalence of domestic abuse and coercive control

- The nature of coercive and controlling behaviours.

1.1 Defining domestic abuse

The UK Government defines domestic abuse as:

The Family Procedure Rules Practice Direction 12J on child contact arrangements and contact orders adds to this definition:

This definition, and an overall shift nationally towards a greater understanding that domestic abuse often involves aspects other than physical violence, has led to the creation of a new legislative framework to criminalise coercive and controlling behaviour.

1.2 Defining coercive and controlling behaviour

Coercive and controlling behaviour is described and defined in different ways in the literature. Hamberger et al (2017) highlight how widespread this inconsistency is. The term ‘coercive control’ is not always directly used within research. Other terms – such as ‘power and control’, ‘domination’ and ‘controlling behaviour’ – may also be used. Follingstad (2007) and Lammers et al (2005) note that a range of overlapping behaviours have significant similarities to the behaviours involved in coercive control. These include emotional abuse, psychological abuse, psychological maltreatment, emotional blackmail, psychological aggression, coercion and verbal abuse. Given its overlap with these other forms of abusive behaviour, it is useful to think of coercive control as an intention or goal and the types of abuse a perpetrator may use as tactics to develop or maintain that control.

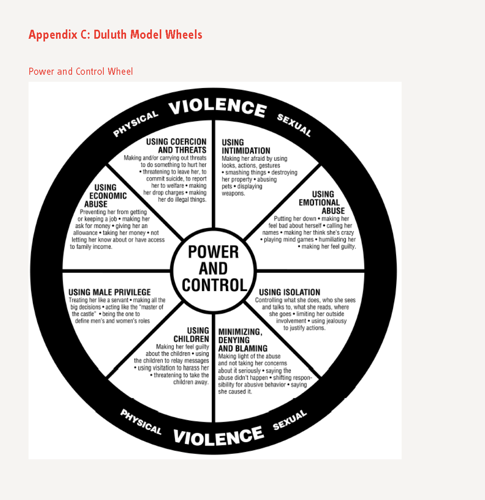

This idea is the central point in one of the first conceptualisations of coercive control, as expressed in the Duluth Model in Minnesota (Pence and Paymar, 1993). The model outlined the ‘Power and Control Wheel’ (see Appendix C) to describe the myriad of behaviours that perpetrators use to control victims of domestic abuse. Power and control is central within the wheel. A number of themes/behaviours around the wheel – such as threats, intimidation, financial abuse and isolation – are the ways in which a perpetrator will seek to establish and sustain control and power over the victim. In the Duluth Model, physical violence is on the outer edge of the wheel; it is a tactic that a perpetrator will use when the abusive behaviours do not work or as a way to ensure the threat of violence maintains the victim’s compliance.

The origins of the term ‘coercive control’ are to be found in debates about the nature, extent and distribution of domestic abuse (Dobash and Dobash, 1992) and whether men and women experience it to similar levels (Straus, 1974). Michael Johnson (1995, 2008) suggests a dualistic typology in which women are disproportionally affected by particular types of abuse, namely coercive control, which he describes as ‘intimate terrorism’. In various studies control is described as being goal-oriented or intentional behaviour by a perpetrator (Hamberger et al, 2017). Beck et al (2009) outline how control is a pattern of behaviour that either partner may use to manipulate or influence the actions of the other.

In the UK the Government has developed a definition of coercive and controlling behaviour.

Overview of cross-governmental definitions (Home Office, 2015)1

|

Control |

Coercion |

|

‘Controlling behaviour is a range of acts designed to make a person subordinate and/or dependent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance and escape and regulating their everyday behaviour.’ |

‘Coercive behaviour is a continuing act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim.’ |

This is the definition also used within Practice Direction 12J on child contact arrangements and contact orders (MoJ, 2017) and Cafcass’s private law Domestic Abuse Practice Pathway, which slightly extends the definition of coercive behaviour.

1 In a consultation ahead of its draft Domestic Abuse Bill, in spring 2018 the Government proposed a slightly revised and statutory definition of domestic abuse, based on the cross-Government definition. The new definition would cover the concept of ‘economic abuse’ rather than simply financial abuse, which ‘can be restrictive in circumstances where victims may be denied access to basic resources such as food, clothing and transportation’. See: https://consult.justice.gov.uk/homeoffice-moj/domestic-abuse-consultation

|

Definition of coercive behaviour in Cafcass’s Domestic Abuse Practice Pathway ‘Coercive behaviour is an act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim. Coercive control involves repeated, ongoing, intentional tactics which are used to limit the liberty of the victim. Those tactics may or may not necessarily be physical. They can be sexual, economic, psychological, legal, institutional, or all of these. By deploying these tactics the abuser can create a world where the victim is constantly monitored or criticised and every move and action checked. Victims often describe coercive control as not being “allowed”, or having to ask permission, to do everyday things; and being in constant fear of not meeting the abuser’s expectations or complying with their demands. The term “walking on eggshells” is often used.’ (Cafcass, 2017) |

The cross-government definition above was introduced in 2013 when, following consultation, the Government extended its definition of domestic violence to include coercive control (Home Office, 2013). It is not a legal definition, however. Coercive and controlling behaviour within relationships was subsequently criminalised in 2015 when the Serious Crime Act 2015 created a new legal definition. In this definition (see below), the effect of the coercive control on the victim is central: effects include causing a fear of violence and having an impact on the victim’s day-to-day life.

Definition of coercive control in the Serious Crime Act 2015

Section 76 of the Serious Crime Act 2015: ‘Controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship’

An offence is committed by ‘A’ if:

- ‘A’ repeatedly or continuously engages in behaviour towards another person, ‘B’, that is controlling or coercive; and

- At time of the behaviour, ‘A’ and ‘B’ are personally connected; and

- The behaviour has a serious effect on ‘B’; and

- ‘A’ knows or ought to know that the behaviour will have a serious effect on ‘B’.

- ‘A’ and ‘B’ are ‘personally connected’ if:

- They are in an intimate personal relationship; or

- They live together and are either:

- members of the same family; or

- have previously been in an intimate personal relationship with each other.

There are two ways in which it can be proved that ‘A’s behaviour has a ‘serious effect’ on ‘B’:

- If it causes ‘B’ to fear, on at least two occasions, that violence will be used against them: s.76 (4)(a); or

- If it causes ‘B’ serious alarm or distress which has a substantial adverse effect on their day-to-day activities: s.76 (4) (b).

We explore the outcomes of criminal cases of coercive control in section 1.3.2. It is worth noting here that the threshold to demonstrate coercive control is lower in the family court, as a person no longer needs to be in a relationship or to live with the perpetrator for coercive and controlling behaviour to be considered. In the family court, in order to be considered as associated to the perpetrator, a victim must be or have at some time been:

- Married, engaged or in a civil partnership with them

- Living together (including as flatmates, partners, relations)

- A relative, including: parents, children, grandparents, grandchildren, siblings, uncles, aunts, nieces, nephews or first cousins (whether by blood, marriage, civil partnership or cohabitation)

- Had a child together or have or have had parental responsibility for the same child

- In an intimate personal relationship of significant duration.

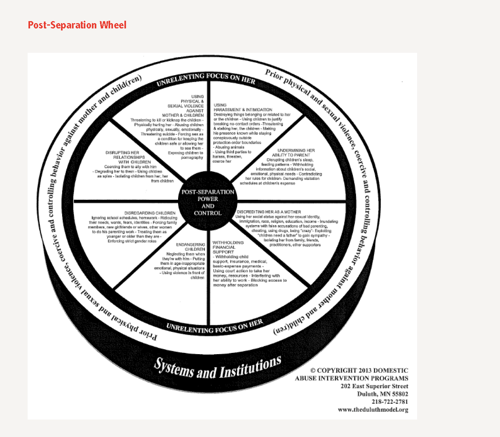

Under criminal law, coercion can no longer take place once a relationship has ended and there is no further cohabitation. However, as discussed in Section 3 of this review, we know that coercive and controlling behaviour commonly persists post-separation.

1.3 Prevalence of domestic abuse and coercive control

1.3.1 Prevalence of domestic abuse

International and national prevalence

Internationally, domestic abuse is recognised to be widespread. The World Health Organization (2013) estimates that 30 per cent of women worldwide will experience physical or sexual violence in the context of an intimate relationship within their lifetime. WHO regional estimates vary between 23.2 and 37.7 per cent, however. For low and middle-income European countries (eg, Lithuania, Romania, Serbia and Turkey), the WHO estimates 25.4 per cent of women will experience violence within an intimate relationship. Estimated prevalence for high-income countries, which includes the UK, is 23.2 per cent.

Data from the Crime Survey for England and Wales suggest around 1.2 million adult women (aged 16 to 59) experienced domestic abuse in the year ending March 2017 (ONS, 2017) – nearly 1 in 17 women (5.9 per cent). On average, every week in the UK two women are killed by a current or former partner.

Prevalence for children and young people

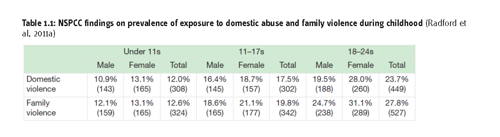

Research for the NSPCC involving a survey of more than 6,000 children and young people [2] in the UK (Radford et al, 2011a) provides us with insight into the numbers affected by domestic abuse. They found 12 per cent of children under the age of 11, 17.5 per cent of children aged 11 to 17, and 23.7 per cent of young people aged 18 to 24 had experienced domestic abuse [3] during their childhood (see Table 1.1). Overall, the study suggests that around one in five children in the UK are likely to have been ‘exposed’ to domestic abuse.

Prevalence of domestic abuse in private and public law proceedings

Hunt and Macleod (2008) estimate that around one in four children in the UK are affected by parental separation. Government statistics show that during the calendar year 2016 over 256,000 new cases began in family courts in England and Wales (MoJ and ONS, 2017), an increase of 4 per cent on 2015. These included nearly 19,000 public law cases, an increase of 18 per cent from 2015 (the number increased by a further one per cent in 2017: MoJ and ONS, 2018). There were 43,327 children involved in public law orders made in 2016 (MoJ and ONS, 2017), while between April 2016 and March 2017 Cafcass received 14,599 care order applications, an increase of 14 per cent on the previous financial year.4

Private law cases starting in the family courts in 2016 increased by 11 per cent over the previous year from 43,347 to 48,244; that number increased by a further 5 per cent during 2017 (MoJ and ONS, 2018). Almost 165,000 children were involved in the private law orders made in 2016 (MoJ and ONS, 2017).

Approximately 10 to 15 per cent of parental separations result in court applications that involve allegations of domestic abuse (Aris and Harrison, 2007). Domestic abuse remedy orders can be applied for through the courts. Remedies include either a non-molestation order (which prohibits contact or activities or behaviour of one person against the other or children) or occupation order (which defines the rights and occupation of the home). In 2016 the courts completed around 19,000 non-molestation and 4,700 occupation applications (MoJ and ONS, 2017). While this gives us an idea of the prevalence of domestic abuse in cases before the courts, the true figure is likely to be higher as a remedy order will not be sought in all cases in which domestic abuse is referenced.

For example, research conducted by Cafcass and Women’s Aid (2017) found that 62 per cent of applications to the family court about where a child should either live or spend time featured allegations of domestic abuse. And in their study, Harding and Newnham (2015) found that 86 (49%) of 174 cases that had gone through the family court system involved an allegation of domestic abuse. Incidents ranged from attempted murder through to common assault and non-physical incidents, such as verbal abuse. The study does not identify how common coercive control was within those cases; however, we provide some estimates in the next section.

1.3.2 Prevalence of coercive and controlling behaviour

Prevalence of coercive control in cases of domestic abuse

While it is possible to estimate the prevalence of domestic abuse by utilising existing national data, understanding how prevalent coercive control is within those abusive relationships is more challenging. This is due to a number of factors, including the way in which agencies currently identify and flag cases that involve coercive and controlling behaviour. Now that the legal definition is in force (coercive or controlling behaviour in an intimate or family relationship became a criminal offence in December 2015 as part of the Serious Crime Act 2015), we will begin to see more robust data emerge with the tracking of the number of prosecutions. Figures were published for the first time in November 2017. These showed 4,246 offences of coercive control recorded for the year ending March 2017 across the 38 police forces that had available data (ONS, 2017).

Table 1.2: Outcomes data for coercive control offences (ONS, 2017)5

| Prosecution commenced at magistrates’ court | Sentenced through court | Convicted through court | Police prosecution | Police cautions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coercive control cases | 309 | 58 | 59 | 155 | 5 |

Another way we can begin to understand how prevalent coercive control is in relationships where domestic abuse is present is by understanding the nature of perpetrators’ behaviour. SafeLives collects the largest dataset in the UK on cases of domestic abuse. SafeLives Insights data6 show coercive control is prominent in the majority of cases receiving specialist support from an Independent Domestic Violence Advocate (IDVA). It shows 82 per cent of domestic abuse victims reported ‘jealous and controlling behaviours’ from the perpetrator and 69 per cent experienced ‘harassment and stalking’ in the three months preceding intake to IDVA services (SafeLives, 2017a). This suggests a high proportion of high-risk domestic abuse cases involve coercive control. Similar findings were found in other specialist support settings (see Table 1.3).

Table 1.3: Overview of coercive control in domestic abuse cases from SafeLives Insights 2014-20177

| % of domestic abuse cases involving jealous and controlling behaviours | % of domestic abuse cases involving harassment and stalking | |

|---|---|---|

| IDVA service* | 82% | 69% |

| Health-based services | 83% | 61% |

| Helpline services | 85% | 63% |

| Outreach services | 72% | 59% |

| Refuge services | 89% | 75% |

*IDVA service data covers 2015-2017 only

Prevalence of coercive control in private and public law proceedings

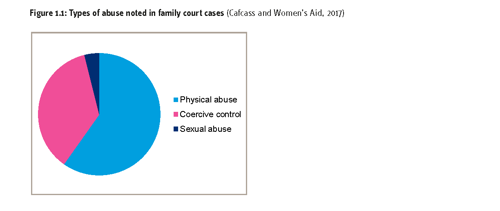

Joint research by Cafcass and Women’s Aid (2017), which analysed domestic abuse allegations in 216 child contact cases, also found high levels of coercive control. In this research the records relating to each case were also considered. Researchers found that 32 per cent of local authority domestic abuse allegations included coercive control, as did 34 per cent of police allegations of domestic abuse.

Challenges in estimating prevalence of coercive control

However, although the SafeLives and the Cafcass and Women’s Aid data do give an indication of the prevalence of coercive and controlling behaviours, the literature highlights some of the difficulties in establishing a more precise and accurate picture of their prevalence within relationships.

Firstly, differences in how coercive control is defined within the literature (as discussed in section 1.2) affect the way in which these behaviours are measured. For example, SafeLives’ Insights data include ‘jealous and controlling behaviour’ as well as ‘harassment and stalking’ as indicators of coercive control. Regan et al (2007) and Thiara (2010) also describe coercive control as including ‘jealous surveillance’. (We discuss the nature of coercive and controlling behaviour more fully in section 1.4.)

A second challenge is that the available data are limited. Walby and Towers (2018) recently concluded that the challenge of estimating the prevalence of coercive control from existing data has not yet been met satisfactorily. In an earlier study, Myhill also concluded that existing data were not robust enough to provide an accurate picture for researchers to measure coercive control (Myhill, 2015).

It is not clear how differences in the definition of coercive control have impacted practice and service delivery. While the Home Office definition has become (since it was introduced in 2013) the most commonly used definition, we can assume there was no consistency in practice nationally prior to this.

1.3.3 Numbers of children and young people affected by coercive control within the family

There are similar challenges and difficulties in estimating how many children live in households where coercive and controlling behaviour forms part of a perpetrator’s tactics. Radford et al’s large survey-based UK study mentioned above (see 1.3.1) gives some indication of the numbers of children likely to be living with domestic abuse. It also found 3.2 per cent of under-11s and 2.5 per cent of 11 to 17-year-olds reported exposure to domestic violence in the previous 12 months (Radford et al, 2011a).

By understanding how many children live in a household where domestic abuse is present, we can then begin also to understand their experiences of coercive control. SafeLives (2017b) data suggest that emotional abuse, trying to intervene and feeling as though they are to blame for the abuse are the most common experiences identified by children who have been living with domestic abuse (see Table 1.4).

Table 1.4: Children’s experiences of domestic abuse: Insights data (n=1,695)8 (SafeLives, 2017b)

| % of cases | |

|---|---|

| Directly involved in abuse of parent | 6% |

| Child or young person (CYP) tried to intervene to stop abuse | 30% |

| CYP feels/felt to blame | 23% |

| CYP emotionally abused as result of abuse | 54% |

| CYP subject to neglect as a result of abuse | 18% |

1.4 The nature of coercive and controlling behaviour

1.4.1 Types of behaviour

In this section we discuss the types of behaviour that a perpetrator may use which can be classified as coercive control. (In Section 2, we will build on this discussion by considering the impacts these behaviours may have – for example, the impact on parenting.)

As discussed in Section 1.2 above, definitions of coercive control differ within the literature. In practice, the Home Office definition is most commonly used, including by Cafcass (as per Practice Direction 12J). For the purposes of bringing together research, however, it is useful to understand the different array of behaviours that are commonly associated with coercive control. The Duluth Power and Control Wheel (see Appendix C) outlines a range of tactics that the evidence shows perpetrators may use to coerce or control victims. In their review of 358 female homicides, Monckton-Smith et al (2017) found control had been present in 92 per cent of cases. Behaviours that demonstrated a perpetrator’s need to control the victim were also prominent. These included stalking behaviours, which were present in 94 per cent of the cases, obsession (94%), fixation (88%) and surveillance (63%).

Table 1.5: Examples of coercive and controlling behaviour

|

Coercive control can include:

(Matheson et al, 2015; Sanders, 2015; Thomas et al, 2014; Stark, 2007, 2009, 2012; Lehmann et al, 2012; Miller et al, 2010) |

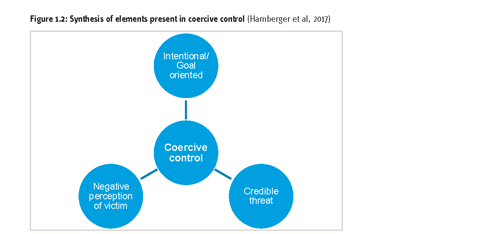

In a recent study Hamberger et al (2017) conducted a literature review of the evidence in relation to coercive control. They found there were three consistent elements that defined coercive control within relationships: intentionality or goal orientation in the abuser; a negative perception of the controlling behaviour by the victim; and deployment of a credible threat (see Figure 1.2). These are discussed below.

1 Perpetrators’ use of ‘credible threat’

The notion of ‘credible threat’ (Hamberger et al, 2017) as part of the array of tactics that define coercive control is referred to by a number of studies. For example Dutton et al (2005) found that coercive control is established through punishment or negative reinforcement, which also underpins the ongoing control throughout the relationship. The type of credible threat perpetrators use will often be physical violence. We can see this through models such as the Duluth Power and Control Wheel in which violence is used as an instrument to enforce regimes of power and control. Hamberger et al (2017) highlight that the threats need to be credible; threats alone do not appear to be directly related to coercive control. There has been significant research that demonstrates how perpetrators will ensure victims are aware of their willingness to deliver negative consequences, in addition to their ability to do so (Day and Bowen, 2015; Krause et al, 2006; Stark, 2007). This means there is some overlap between violence and coercive control, making their separation challenging. (This is discussed further in Section 1.4.2.)

One focus for perpetrators’ threats is use of the home – for example, threats of homelessness or making clear that they will find a victim’s new location if the victim attempts to flee. We know that families who experience domestic abuse often move location multiple times. Radford et al (2011b) found in their interviews with 37 mothers in London that the majority had moved at least once. The researchers also interviewed children and young people who had lived with domestic violence. Two siblings under nine years old had moved home eight times and changed school seven times to try to escape the perpetrator. The credible threat perpetrators pose in relation to housing is particularly pertinent in relation to child contact because many professionals (eg, social workers and police, as well as housing officers) encourage victims to move home – and preferably some distance away – to ensure perpetrators will not be aware of their location (Radford et al, 2011b). However, child contact was often the last form of control perpetrators could use to locate victims, as family courts would often grant contact.

The victim’s role as a parent is often threatened by a perpetrator in order to control the victim. For example, perpetrators may use the threat of statutory services or having the children removed if the victim does not comply. Lapierre (2010a) found some women would avoid disclosing to agencies due to fear of the potential adverse consequences of having their children removed. Stark (2007) states that threats to take or harm the children and the practice of mother-blaming are part of a perpetrator’s coercive and controlling behaviour, and can make women fearful about disclosing the abuse. Women fear being perceived as a ‘bad mother’, a fear often reinforced by the perpetrator.

2 A perpetrator’s intention or goal in the context of coercive control

The idea that coercive control is routinely driven by the intent of a perpetrator to achieve a particular goal is consistent with other research (Stark, 2007; Day and Bowen, 2015). While some studies suggest that particular behaviours may be coercive without the perpetrator recognising them as such (Dutton et al, 2005; Ehrensaft et al, 1999), most research indicates perpetrators are aware that their behaviour is coercive and have a clear goal in mind, which is to exert power over the victim. Stark (2007) explains that coercive control is used to suppress potential conflicts or challenges to a perpetrator’s authority, and not as a result of conflict or stress. In order to exert power and control over victims, perpetrators may use a range of goal-oriented behaviours as described below.

Isolation

Williamson (2010) suggests behaviours are used to isolate women from their network of support. This has the benefit of ensuring perpetrators can continue to control victims with little challenge from others. Monckton-Smith et al (2017), reviewing 358 cases of homicide committed by men against women between 2012 and 2014, found isolation by the perpetrator in 78 per cent of these cases. We therefore know that isolation is a key tactic used to control victims. In their triennial review of almost 300 serious case reviews, Sidebotham et al (2016) identified a pattern – victims in a relationship with ‘aggressively controlling men who would isolate those women, impose restrictions on them, and control many aspects of their lives’ – that often had fatal consequences for children. (We explore this more in section 1.4.3.)

Isolating women from their network of support often extended to the experiences of children also. In her interviews with 15 mothers and 15 children who had lived with coercive control, Katz (2016a) found that when a perpetrator controlled the mother’s movements, this also severely restricted the children’s ability to form social lives and peer networks. It would prevent them from engaging with wider family, peers and extra-curricular activities, for example.

In Coy et al’s (2012) study, the methods perpetrators would use to isolate victims included unrealistic expectations of chores to be completed in the home. This meant some women were too anxious to leave the house in case they had forgotten to complete a task. Katz (2016b) found women would avoid going to the supermarket or having children’s parties, as the perpetrator would accuse them of having an affair. Such isolating behaviours often meant children’s opportunities to create resilience-building relationships with non-abusive people outside their immediate family were limited or denied, as were opportunities to experience the multiple benefits that engaging positively with grandparents, friends or after-school clubs can have on children’s social skills, confidence and development (Katz, 2016b).

Perpetrators’ tactics to isolate women from support networks can affect the way victims engage with services. Women may be fearful of speaking to agencies (eg, police or social workers) in case the perpetrator finds out and it makes things worse. This is often also the case for children, who may see speaking out as ‘risky and dangerous’ (Callaghan et al, 2017). Radford et al (2011b) found some children thought speaking to teachers or friends at school about what is happening at home could make things worse. Perpetrators trap mothers and children in ‘unrealities’ shaped by manipulations, distortions, excuses, minimisations and denials which are designed to keep them confused and compliant (Williamson, 2010).

Distorting reality

Researchers have identified other common behaviours that perpetrators use to exert power and control over victims. These include making women question their own reality or, as some have described it, making them feel that they are ‘going mad’. This is referred to in some literature as ‘gaslighting’ (Tracy, 2016). In Enander’s (2011) research, victims spoke about the way in which perpetrators would present as a Jekyll and Hyde character. This meant they would behave positively in public by showing affection and charm, whilst at home behaving negatively through dominance and abuse.

Table 1.6: Coercive control tactics used by perpetrators (Coy et al, 2012)

- Refusing to tell women their shift patterns so they were unable to plan seeing friends or childcare

- Turning women’s alarm clocks off so that they were late for work

- Threatening to plant drugs on women and report them to the police if they tried to leave

- Undoing women’s housework then telling them they had not even started it.

Some women who have experienced perpetrators creating a public persona different to that displayed at home have discussed the barrier this creates in terms of their ability to disclose abuse for fear they will not be believed (Coy et al, 2012).

Deprivation of resources

There is much research exploring the intent of perpetrators’ behaviour in relation to the goal they seek to achieve. Most notably, Kelly et al (2014) coined the term ‘space for action’ in order to describe the intent of perpetrators in limiting victims’ ability and capacity to make choices. Perpetrators use an array of behaviours to do this; these were included in the development of a number of new measurement tools created through Kelly et al’s research. In limiting a victim’s space for action, perpetrators will often limit or deprive them of resources such as money, food, transport or heating.

Thiara (2010) describes perpetrators’ ‘micro-management’ in relation to their partners, which often involves limiting access to money. Based on the survey responses of 49 women who had experienced economic abuse and individual interviews with 20 of the women, Sharp (2008) identified four different themes or ‘types’ of economic abuse: interfering with women’s employment; preventing women from having money; refusing to contribute to household bills; and creating debt for which women are liable. In their more recent research, Sharp-Jeffs and Learmouth (2017) highlight the way in which perpetrators may interfere with a victim’s ability to acquire, use or maintain economic resources.

Table 1.7: Overview of economic abuse (Sharp-Jeffs and Learmouth, 2017)

|

Acquire |

Use |

Maintain |

|---|---|---|

|

Interfering with/sabotaging partner’s education, training and employment; preventing partner from claiming welfare benefits. |

Demanding receipts, checking bank statements; keeping financial information secret; making partner ask to use car/ phone/utilities; threatening to throw partner out of home. |

Refusing to contribute towards household bills and the cost of bringing up children; spending money set aside for bills; generating costs, such as destroying property that then needs replacing; using coercion/fraud to build up debt in victim’s name. |

These techniques reduce the victim’s capacity to be able to parent by limiting their access to the resources they require. Through economic abuse, perpetrators can ensure a victim uses all her resources on bringing up the children, leaving nothing to spend on other areas of her life, or ensure she relies solely on the perpetrator to be able to provide what the children need, thereby limiting the victim’s ability to leave the relationship.

Katz (2016b) describes a number of ways in which a perpetrator may deprive a mother and her children of basic resources. One mother and son reported how the perpetrator would:

- Tell them they couldn’t touch the food in the fridge, limiting their ability to eat.

- Unplug communications technology (eg, phones and internet) to limit their ability to contact the outside world – this also restricted the son’s ability to do his homework and the mother’s access to money through online banking.

- Lock them in the house when he went out, preventing them from leaving the home.

- Disconnect the electricity, limiting their ability to keep warm or wash, turn on lights or watch TV.

These examples demonstrate how a perpetrator’s coercive and controlling behaviour impacts the whole family, and not only the primary adult victim. Katz (2016a) poses the question as to whether coercive control should in fact be seen as a form of child abuse in its own right. (We explore the links to other forms of child abuse in section 1.4.3.)

Surveillance and monitoring

Monitoring is another common tactic used to limit victims’ space for action. Controlling or coercive behaviour is not confined to the home; the victim can be monitored from a distance by phone or social media (Home Office, 2015). Research demonstrates that this type of behaviour, which can be described as ‘jealous surveillance’ (Regan et al, 2007; see also Thiara, 2010), can result in accusations of unfaithfulness, resulting in women having to stay at home to avoid further conflict.

3 Victims’ negative perceptions of coercive and controlling behaviour

The third facet of coercive control identified by Hamberger et al’s (2017) literature review is that the coercive control is perceived negatively by victims. This is demonstrated by a number of studies. For example, through their interviews with over 50 women who had experienced domestic abuse, Coy et al (2008) found that all described the abuse in similar terms, which included emotional abuse, psychological tactics, mental bullying, mind manipulation, being belittled and demeaned. These descriptions highlight that victims are clear that the perpetrators’ behaviours are negative.

1.4.2 Links to violent behaviour

Coercive control and violence are inextricably linked. Perpetrators may use physical violence to create and sustain control over victims (Hamberger et al, 2017). Perpetrators may also create a fear of violence to enforce their regime, which means violence can often become a consequence of control (Johnson, 2008; Lammers et al, 2005). As discussed in Section 1.2, the Duluth Model places violence as the outer shell of perpetrators’ controlling and coercive behaviour. It suggests that victims become susceptible to these forms of control out of a fear of violence if they do not comply. Although some perpetrators may use physical violence frequently, we know others will use little or none. Rather, some perpetrators will prefer to maintain dominance over their partner through psychological abuse and the control of time, movement and activities (Westmarland and Kelly, 2013; Johnson, 2008). Perpetrators may see physical violence as a last resort because it is more likely to draw attention to their abuse (Coy et al, 2012).

A number of studies place violence, intimidation and threat as key factors in how perpetrators will establish coercive control (Beck et al, 2009; Cook and Goodman, 2006; Miller and White, 2003; Stark, 2007). This suggests that coercive and controlling behaviours alone are not violent, but rather that violence is used to enable coercive control.

Not all academics agree with this approach, however. For example, Walby and Towers (2018) describe how coercive control is now being interpreted in public debate as focused on non-physical abuse, such as emotional abuse, rather than on physical violence. They place coercive and controlling behaviour as a form of violence itself. Other researchers have also highlighted how coercive control is violent behaviour. Cook and Goodman (2006) describe how perpetrators can use violence unpredictably as a means of creating terror, which is a form of coercive control. This makes the separation of coercive control from violence a challenge.

1.4.3 Links between domestic abuse and other forms of child abuse

Domestic abuse can itself be classified as causing direct harm to children. The Adoption and Children Act 2002 (s.120) extended the legal definition of ‘harm’ (as stated in s.31 of the Children Act 1989) to include the ‘impairment suffered from seeing or hearing the ill-treatment of another’; this definition came into force in 2005. As well as harm resulting directly from the domestic abuse itself, children may experience direct harm through wider forms of abuse that are often linked to domestic abuse. For example, Humphreys and Thiara (2002) and Mullender et al (2002) both found co-occurrence of children experiencing physical or sexual abuse as well as domestic abuse. Devaney (2015) suggests three reasons why domestic abuse perpetrators may also engage in child abuse:

- Violent adults often may not discriminate between different family members.

- Adult victims may not be able to meet the physical, emotional or supervisory needs of their children as a result of physical injury and/or poor mental health.

- Children may be injured while trying to intervene or while being carried by the adult victim at the time of assault.

Sidebotham et al (2016) emphasise that ‘living with domestic abuse is always harmful to children’ and that it is rightly seen as a form of child maltreatment in its own right (Humphreys and Bradbury-Jones, 2015). Citing research by McGee (2000) and Mullender et al (2002), Harne states:

From this we can begin to piece together the ways in which a perpetrator’s coercive and controlling regime will impact on children and young people, and in some instances link to wider forms of abuse. Earlier research by Kelly (1994) described perpetrators’ behaviour having ‘double intentionality’, which often results in children being directly abused. This double intentionality means perpetrators:

- Abuse the mother by abusing and mistreating the children

- Abuse the children by exposing them to, and involving them in, the abuse of the mother.

We deal with the second of these intentions in Section 2 where we discuss the impact on the family. In this section, we will now consider Kelly’s first point by exploring the links between domestic abuse and forms of child maltreatment, namely: neglect, emotional abuse, and physical harm and homicide.

1 Domestic abuse and neglect

In their national UK study, Radford et al (2011a) found that children who had lived with domestic abuse were between 2.9 and 4.4 times more likely to experience physical violence and neglect than young people who had not lived with domestic abuse. Domestic abuse can itself result in forms of child abuse such as neglect and/or emotional abuse. Neglect, which is the most common form of child abuse in the UK, is defined in statutory guidance as the persistent failure to meet a child’s basic needs (HM Government, 2018). It can involve physical neglect, educational neglect, emotional neglect or medical neglect (NSPCC, 2017). As described by the NSPCC, this may include a child being ‘put in danger or not protected from physical or emotional harm’.9 When a perpetrator is being abusive or violent within the home, it can be argued they are failing to protect their child from emotional harm.

Despite its age, Christine Cooper’s (1985) checklist of a child’s seven basic needs is still commonly used by practitioners across the country. Security is one of those basic needs. It is defined as ‘continuity of care, the expectation of continuing in the stable family unit, a predictable environment, consistent patterns of care and daily routine, simple rules and consistent controls and a harmonious family group’ (Cooper, 1985). It is clear from the definition of domestic abuse that patterns of coercion and control do not provide a stable, predictable or harmonious family unit. Perpetrators’ behaviour can therefore be seen as neglectful.

2 Domestic abuse and emotional abuse

|

Definition of emotional abuse from Working Together to safeguard children: A guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and protect the welfare of children (HM Government. 2018) ‘The persistent emotional maltreatment of a child such as to cause severe and persistent adverse effects on the child’s emotional development. It may involve conveying to a child that they are worthless or unloved, inadequate or valued only insofar as they meet the needs of another person. It may include not giving the child opportunities to express their views, deliberately silencing them or ‘making fun’ of what they say or how they communicate. It may feature age or developmentally inappropriate expectations being imposed on children. These may include interactions that are beyond a child’s developmental capability, as well as overprotection and limitation of exploration and learning, or preventing the child participating in normal social interaction. It may involve seeing or hearing the ill-treatment of another. It may involve serious bullying (including cyber bullying), causing children frequently to feel frightened or in danger, or the exploitation or corruption of children. Some level of emotional abuse is involved in all types of maltreatment of a child, though it may occur alone.’ |

The definition of emotional abuse is set out in the Government’s statutory guidance, Working Together to Safeguard Children (HM Government, 2018). As we have seen, s.120 of the Adoption and Children Act 2002 (introduced in 2005) also extended the concept of ‘significant harm’ to include ‘impairment suffered from seeing or hearing the ill-treatment of another’. Referrals to Children’s Services increased steadily following this amendment (Radford et al, 2011b).

SafeLives Insights data demonstrate the varying ways in which coercive control may overlap with child abuse, including emotional abuse. In addition to seeing their non-abusive parent subjected to the perpetrator’s ongoing control, we know a high proportion of children live in fear of being harmed themselves. Analysis of the Insights data collated by SafeLives (2017b) reveal that four out of ten (41%) children who had lived with domestic abuse were afraid of being harmed themselves and six out of ten (59%) feared their parent may be harmed, a finding which demonstrates emotional abuse (see Table 1.8).

Table 1.8: SafeLives Insights data of children’s experiences of domestic abuse (n=1,695) (SafeLives, 2017b)

| Experience of abuse | % of cases |

|---|---|

|

Often at home when abuse took place |

95% |

|

Child or young person is/was a direct witness to the abuse |

74% |

|

CYP injured as a result of abuse of a parent |

10% |

|

Non-abusing parent fearful of harm to child |

33% |

|

CYP fearful of harm to self |

41% |

|

CYP fearful of harm to parent |

59% |

|

CYP tried to intervene to stop abuse |

30% |

|

CYP emotionally abused as result of abuse |

54% |

|

CYP subject to neglect as a result of abuse |

18% |

Although the Insights data (SafeLives, 2017b) highlight that around half (54%) of children living with domestic abuse will be emotionally abused, Harne (2011) found few perpetrators understood that domestic abuse would be emotionally abusive to children. Similarly, in their survey of 3,234 perpetrators who had been convicted of domestic abuse, Salisbury et al (2009) found the majority had not considered the impact of their behaviour on their children. Interestingly, the desire to change behaviour to reduce the impact on children has been found to be a key motivator for behavioural change (Stanley et al, 2009), which suggests interventions should focus on raising this awareness.

Victims can also underestimate the impact a perpetrator’s non-physical tactics can have on children. For example, Radford et al (2011b) found some mothers believed their children were not at risk if they were not physically harmed. They suggest mothers are often preoccupied with trying to keep themselves and their children safe, and that the impact coercive control and abuse may have on the children can be overlooked.

Harne (2011) also found that the way in which perpetrators interact with children differs from non-abusive fathers, often resulting in inconsistent care, which in itself could be considered neglectful or harmful. Fox and Benson (2004), for example, found that violent men often used more punitive behaviours and less positive parenting behaviour than non-violent men. This does not tell us much in terms of men who use coercive control specifically, but as we know from research findings described in earlier sections, men who use violence are likely to do so to enforce control. Therefore we can make some assumptions that violence will be used to express control over children also. In addition, behaviour that may appear to be positive parenting can in fact be a demonstration of power and control. Bancroft and Silverman (2002) discuss how abusive fathers’ ‘declarations of love’ would often reflect the father’s opinion that children are ‘emotional property’, rather than being a true expression of care for the child’s wellbeing.10 More recently, Bancroft et al (2012) found that fathers who are perpetrators of abuse have common parenting styles (see Table 1.9); a characteristic of all three styles identified by the authors is that the perpetrator had a poor understanding of children’s development and needs. Adding to the unpredictability of living with coercive control, a perpetrator’s parenting style will often alternate on a day-to-day basis.

|

Table 1.9: Parenting styles of perpetrators of domestic abuse (Bancroft et al, 2012)

|

The Insights data (SafeLives, 2017b) highlight that 95 per cent of children living in households experiencing abuse are at home when abuse is taking place and 74 per cent witness abusive incidents directly. However, coercive control is not a series of isolated instances, but rather an ongoing and sustained pattern of behaviour. We know that victims experience coercive control as something that is ongoing and has a cumulative impact (Morris, 2009; Stark, 2007, 2009); we can assume the experience for children will not be dissimilar. A number of longitudinal studies of children who have experienced domestic abuse (and other forms of maltreatment) suggest adversity may accumulate over time, with effects becoming more entrenched. Hester and Pearson (1998), Cawson (2002) and Humphreys (2000) all found that both the severity of the violence and abuse, and the period of time over which it continues, increase the risk to children and worsen the impact and outcomes for children.

In addition, the different types of abuse a child may face can increase the negative impact for a child. Rutter (1985, 1987), for example, found six factors that were associated with poor adaptive outcomes for children, one of which was domestic abuse. The more factors a child faced, the more likely they were to experience adverse outcomes. Hughes et al (1989) considered the impact of domestic abuse based on how children experience it. They found children who experienced direct abuse, as well as witnessing abuse between parents, were more likely to display problematic behaviours compared to those who had witnessed abuse but not been directly abused. Based on this research, we can assume that children who are exposed frequently to coercive control will accumulate higher levels of harm over time. This is likely to be exacerbated for young people who also witness the abuse of parents and are harmed directly.

3 Domestic abuse, physical abuse and child homicide

It is worth noting that children will often be abused directly as part of a perpetrator’s abuse. The Insights data (SafeLives, 2017b) found that 10 per cent of children sustained injuries as a direct result of domestic abuse. Coy et al (2012) heard accounts of perpetrators using physical violence towards children:

Dallos and Vetere (2012) suggest violence and intimidation are often directed at children as well as the adult victim, making the separation of domestic abuse and child abuse challenging. Hester (2000) adds that children can often be abused in the context of domestic abuse as a perpetrator’s strategy to further intimidate and control their partner. This is demonstrated in a quote from Coy et al (2012):

There is also significant overlap with child homicide (SafeLives, 2014; Hester, 2000; Humphreys, 2007; Jaffe et al, 2012; Radford et al, 2013). An overview of serious case reviews (SCRs) in England identified high levels of domestic violence in the cases studied (Brandon et al, 2009). In her study of child homicides by 13 fathers (29 children, 13 families), Saunders (2004) found that in five cases the killings appeared to have been conceptualised by the father as a form of revenge on the children’s mother. More recently, in their review of 293 SCRs Sidebotham et al (2016) found that domestic abuse was a feature in almost all instances of overt filicide. This ranged from cases with a history of overt and severe physical violence to a high number that involved aggressive coercive control. These often included cases that seemingly went ‘under the radar’ and did not raise professionals’ level of concern or include a disclosure from the victim:

Section 2: The impact of coercive and controlling behaviour on the family

There is a substantial evidence base describing the impact coercive and controlling behaviour has on victims. Coercive control reduces a victim’s power to make decisions, which limits the ability to exercise independence (Robertson and Murachver, 2011), and it is widely recognised throughout the literature that coercive control impacts a victim’s whole life, including their interpersonal relationships, education and employment opportunities, and use of economic resources (Kelly et al, 2014; Bair-Merritt et al, 2010; Beck et al, 2009; Robertson and Murachver, 2011; Stark, 2007). We can assume that coercive control will also have a significant impact on children who have experienced this form of abuse, and on the relationship between children and their parents. This section aims to bring together what we know about the impact on the family as a unit. We will focus primarily on:

- The impact on parenting

- Children’s role within the family in the context of coercive control

- Children’s experiences of coercive control

- The impact of coercive control on children.

2.1 Impact on parenting

There has been significant research exploring the impacts of domestic abuse and coercive control on a victim’s ability to parent. In the instance of coercion and control, there are clear examples of perpetrators using children to abuse their mother. These include alienating the mother from the family by forming an alliance with the children and undermining the mother’s role as a parent. This section will explore how these tactics feature as part of a perpetrator’s overall coercive and controlling regime.

2.1.1 Maternal alienation (as a tactic of coercive control)

Morris (2009) highlighted the term ‘maternal alienation’ which is used in much of the literature to describe the way in which perpetrators will systematically attempt to alienate children from their mothers to prevent them forming an alliance. It is important to note here that we are not discussing parental alienation in the context of the High Conflict Practice Pathway (currently being developed by Cafcass), which focuses on alienation after separation11. Rather, we are discussing the ways in which perpetrators of domestic abuse will systematically alienate the victim from the family unit by recruiting children into the abuse. Unlike parental alienation in relation to the high conflict pathway, parental alienation within the context of domestic abuse has a clear intent to exert power or control over a victim and will often be used within the relationship as well as during and after separation. We will explore three ways in which perpetrators alienate mothers within the context of domestic abuse: forming an alliance with children to recruit them to directly abuse their mother, demeaning the mother and recruiting wider family members.

Perpetrators can disrupt the relationship between the victim and their children by using the children as part of their coercive control tactics. Bancroft and Silverman (2002) explain that perpetrators achieve power and control within the household by emotionally manipulating children into forming an alliance with them that undermines the mother-child relationship and isolates the mother within the family. The study highlights how a perpetrator may ‘joke and play, spend money on them [the children], or take them out to do things’ in order to form an alliance, which can result in children seeing the abusive parent as ‘fun’ and blaming the non-abusive parent for the abuse. In their research with victims of domestic abuse who were going through court to arrange contact, Coy et al (2012) found that perpetrators would seek to form an alliance with children by involving them in the abuse of the victim.

SafeLives Insights (2017b) data support the notion that in some cases perpetrators alienate the victim by involving children in the abuse, finding that six per cent of children were involved directly in abusing the victimised parent. Similarly, Radford and Hester (2006), Thiara and Gill (2012) and Katz (2016a) all found that a child’s relationship with their mother is often directly targeted by the perpetrator, with children being manipulated to act abusively towards their mother, particularly (but not exclusively) in the context of child contact. This manipulation may include the perpetrator making threats or offering bribes to ensure the child complies.

Hardesty et al (2016) describe how children can be enrolled in coercive behaviours, used as tools to exert control and be direct victims of controlling and coercive acts. In their study involving mothers who had recently separated, the researchers categorised the mothers into three groups: no violence (n=74), situational couple violence (n=46) or coercive controlling violence (n=34). They found the latter group had the poorest quality of co-parenting. That group also reported considerable levels of fear that the perpetrator would continue harassment, which was cited as the biggest barrier to co-parenting.

Many studies include women’s accounts of how perpetrators would demean and abuse them in front of the children (see, for example, Coy et al, 2012). Perpetrators deliberately disrupt the trust and emotional relationship between the victim and their children as a strategy to isolate the mother and maintain control (Humphreys et al, 2006). This isolation is exacerbated by the fact that many perpetrators will also isolate victims from external influences such as peers, wider family or support services, so children may be the only form of contact a victim has. Mullender et al (2002) found perpetrators would use a number of strategies to alienate victims from their children. Tactics can include ‘demeaning women in front of the children, recruiting children in the abuse of their mothers, and diminishing women’s abilities as mothers’ (Coy et a, 2002).

Parental alienation could also include the wider family network. For example, Thiara’s (2010) research of coercive control within South Asian families in the UK found that perpetrators would deny victims a relationship with their children and often reinforce this in collusion with their own parents and siblings. The perpetrator’s family can also be involved in controlling and denigrating the victim.

2.1.2 Undermining the victim’s role as a parent

Perpetrators can undermine a victim’s parenting ability, making them feel they are not a good enough parent. Lapierre (2010a) states that ‘men’s attacks on mothering and mother-child relationships are central in their exercise of control and domination’. Radford and Hester (2006) explain that women experiencing domestic abuse will often lose confidence in their parenting ability and capacity. The tactics a perpetrator will use to undermine the victim’s parental role will often leave them feeling emotionally drained and distant and as though they have little left to give as a parent.

As explained by Bancroft and Silverman (2002), one way in which perpetrators may seek to undermine a victim’s role as a parent is by encouraging children to question their mother’s authority. This same strategy was identified by Coy et al (2012) in their interviews with more than 30 victims of abuse.

A number of studies describe how children can be directly involved in coercive and controlling activities, which may serve the purpose of undermining the non-abusive parent’s parental role. These include isolation, blackmailing, monitoring activities and stalking; these can also be used in other ways by abusers to minimise, legitimise and justify violent behaviour (Johnson, 2008; Stark, 2007). Perpetrators will often attempt to damage children’s respect for their mother, prevent the mother from being able to provide consistent routines and attempt to turn the children against their mother.

Stanley (2011) describes how this type of behaviour can impact on children by teaching them that their mother is not deserving of respect. Children act accordingly, treating their non-abusive parent with no respect. This creates a cycle in which the mother begins to feel her relationships with her children are stressful, unhappy and beyond her control. With her authority undermined, it then becomes difficult for mothers to develop and enforce boundaries within the home. This deepens the victim’s need in relation to the perpetrator, as children may not listen to them when the perpetrator is not around.

Another way in which perpetrators of coercive control undermine a victim’s role as a parent is by constraining their ability to parent. Katz (2016a) found perpetrators would demand a high level of attention from mothers, which would be at the expense of her children. In her study she offers examples such as a victim attempting to brush her daughter’s hair and the perpetrator saying ‘You’ve spent enough attention on her, what about my attention?’ and a daughter describing how whenever her mother would sit down to play with her, the perpetrator would call the mother into another room. Coercive control limits the amount of maternal attention children are able to enjoy and reduces opportunities for fun and affection (Katz, 2016a).

Anderson and Saunders (2003) explain that the tactics a perpetrator will use to undermine a victim’s ability to parent will often include an element of unpredictability whereby the perpetrator alternates between periods of abusive and loving behaviour, blaming their partner for the violence and/or claiming that they can change. Overall the impact of maternal alienation creates significant barriers in the mother-child relationship, alienating one from the other. This is something to be considered during both private and public law proceedings, as relationships between the child and perpetrator and the child and mother may be complex to unpick as a direct result of children being systematically alienated from their mother.

2.1.3 Victims as protective parents

There is a general consensus within the literature that supporting the non-abusive parent to protect their children is often the most effective form of prevention and protection for children (Humphreys and Absler, 2011). However, it is important to understand the context of coercive control and how this can impact a mother’s ability to be protective. Stark comments:

When understanding the protective behaviours of mothers, we must view their actions and behaviour in the context of a restricted ‘space for action’, rather than by the standards of societal expectations. Wendt et al’s (2015) study found two main ways in which mothers will commonly seek to protect their children:

- Protection as an act to stop physical violence being perpetrated on their children by their partner.

- Protection as a constant process they engage in to create an environment that is free of violence and provides some form of stability or normality for their children.

In particular, coercive control will mean women face significant barriers in disclosing their own or their child’s suffering; rather, they may try to manage the harm and risk themselves. From their analysis of almost 300 SCRs, Sidebotham et al (2016) highlight the finding that repeated opportunities, in a safe and trusting environment, are necessary to encourage disclosure. It is important, therefore, that mothers who do not disclose domestic abuse are not seen as not being protective; rather, a mother may feel that by avoiding professionals’ input she is reducing the risk of harm the perpetrator poses to herself and her children.

Lapierre (2010b) interviewed 26 victims of domestic abuse and identified a number of ways in which they would attempt to manage the perpetrator’s behaviour in order to protect their children. For example, women tried to monitor their partners’ moods and prevent violent incidents by behaving in ways that would not upset their partners. They also tried to shield the children during violent incidents by ensuring they were in another room or away from the house. Some had challenged their partners’ violent behaviour and asked them to leave.

Sidebotham et al (2016) emphasise the need for professionals to understand a mother’s behaviour in the context of her experience of coercive control, which may not always make sense to professionals. Sidebotham et al’s case example (see box) of a pregnant mother discharging herself from hospital highlights the perception professionals may have. However, in this case the mother was balancing managing the risk to all her children, something medical staff were not aware of at the time. It is an example of the sorts of explanation it is important for professionals to consider if a victim of coercive and controlling behaviour takes actions that do not seem protective.

|

Case example from triennial review of SCRs (Sidebotham et al, 2016) When … a pregnant mother discharged herself from hospital against medical advice and appeared to be acting against the best interests of her unborn baby, she may actually have been doing her best to protect her older children who were at home in the care of her controlling partner. |

Sidebotham et al also found that in response to threats and coercion from the perpetrator, some women may play down the impact or harm resulting from the abuse, both to themselves and their children. This can be a direct strategy to avoid contact or assessments from services, which may provoke a negative reaction from the perpetrator.

Haight et al (2007) interviewed 17 mothers who had experienced domestic abuse and identified a number of strategies mothers use to protect children from the impact of the abuse (see Table 2.1). Interestingly, mothers did not feel able to develop strategies that directly challenged or sought to change perpetrators’ behaviour; rather, the strategies focused on limiting children’s exposure to the behaviour and providing a buffer to its impact by discussing the behaviour.

Table 2.1: Protective strategies described by mothers (Haight et al, 2007)

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Reassuring and supporting |

Mothers described the importance of providing their children with emotional support, including reassuring them that they are loved, they will be taken care of, they are safe now, the fighting was not their fault, and leaving was a good decision. |

|

Limited truth-telling |

Mothers emphasised the importance of providing children with factual information, but doing so in a way that does not further traumatise them. Mothers stressed, ‘don’t lie to them about it’ and, ‘answer their questions’. The challenge is to provide enough information to honestly address the child’s concerns without causing additional distress. |

|

Instilling hope |

Mothers also discussed the importance of instilling hope in their children by directing their attention to the future or, if the abuse had ended, the present. Mothers spoke of the importance of helping children to ‘move on’ and not ‘dwell’ on the trauma, and of letting the child know that ‘things will get better’. |

|

Prevention education |

Mothers stressed to their children that violence is wrong, taught alternative responses to interpersonal conflict, and provided substance abuse education.

|

There is some evidence that suggests victims’ protective strategies identified by Haight et al are in line with children’s wishes. For example, when Mullender conducted a focus group with children who had experienced domestic abuse, one child said:

This is useful to consider when seeking a child’s views and wishes as part of private and public law proceedings.

In their interviews with 23 children, Radford et al (2011b) found the majority had confidence in their mother’s ability to protect them from abuse by the perpetrator. Some recognised this would be difficult, however. In one example the mother would provide her children with guidance on how to keep safe.

Children’s examples of how their mother tried to protect them included moving house or going to a friend or family member’s house until Dad was ‘in a good mood’. Interestingly, most children’s perception of what a non-abusive parent could do to protect them in the context of domestic abuse was to create physical space between them and the perpetrator (Radford et al, 2011b). This is often not possible when contact arrangements have been made through the court, however. In their interviews with children, Mullender et al (2002) also found mothers were seen as the children’s most important source of help and main source of support in coping. This suggests interventions that support positive reinforcement in this role could be crucial for the improved wellbeing of children living with coercive control.

When discussing victims of domestic abuse as protective parents, it is vital professionals avoid victim blaming and that perpetrators are held solely responsible for harm to children that has resulted from the abuse. This was a finding from Women’s Aid’s (2016) review of 19 child homicides. Within the SCRs, researchers found a number of instances where professionals criticised mothers’ choices rather than focus on limiting, disrupting or challenging perpetrators’ use of coercive and controlling tactics, which no doubt would have influenced her ability to take action.

2.2 Children’s role in families where there is coercive control

2.2.1 Triangulation

Descriptions of the role of children living in a context of coercive control differ in the literature. In some studies children are referred to as ‘witnessing’, in others as ‘exposed to’ and in some as ‘victims’. A review of 177 articles relating to domestic violence and abuse found that 85 per cent described children as being ‘exposed to’ domestic violence and 67 per cent used the term ‘witness’ (Callaghan et al, 2015). The authors discuss how much of the literature around children’s role within domestic abuse involves them being ‘collateral damage’ to adult domestic abuse. They argue that by positioning domestic abuse as a dyadic relationship we ignore the direct role children play within a context of coercive control and abuse. While there is no statutory definition, the description used most often is ‘children who experience domestic abuse’, which does take into account the varying forms the experience may take. The statutory definition of domestic abuse clearly states that victims are aged 16 and over, therefore children would not be considered victims of domestic abuse.

Dallos and Vetere (2012) suggest children are often drawn into the dynamics of the parental dyad and that we should understand the dynamic as ‘triangulation’. Within the context of coercive control, triangulation can often involve conflict, distress and force children to establish coalitions and alliances against a parent. As discussed earlier in section 2.1, perpetrators will often form alliances with children against the victim (Coy et al, 2012; Mullender et al, 2002; Thiara, 2010) so understanding how children experience this role is important.

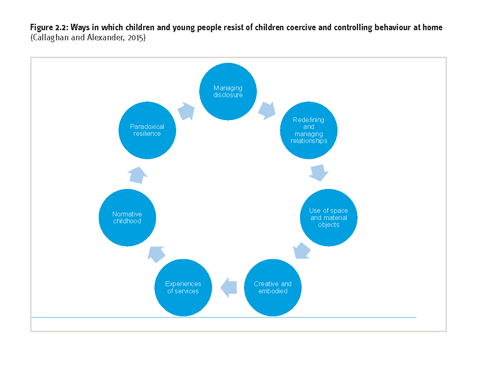

2.2.2 Children as agents (rather than passive) in the context of coercive control

It is important to understand the role that children play in settings where there is coercive control. A number of studies have noted that in order to support children effectively, it is important they are not viewed as having been ‘exposed to’ or ‘witnesses’ to domestic abuse; rather, children should be seen as ‘human beings who live with, experience and make sense of’ (Callaghan and Alexander, 2015) domestic abuse (Mullender et al, 2002; Øverlien, 2011). If we are to consider this explanation of the role children play within domestic abuse, then we must consider also how their role as agents within the family home impacts their experience of coercive control. In their research, in which they interviewed 21 children about their experiences of domestic abuse, Callaghan et al (2015) echo these findings. Children recounted the disruption and distress they experienced as a consequence of coercive control within the family setting. The authors argue this demonstrates that children are not passive, but immediately involved and affected by coercive and controlling behaviour. Perpetrators’ behaviours are not limited to targeting the adult victim, they argue; rather, the entire family is targeted.

Mullender et al (2002) categorised children’s involvement in domestic abuse in three ways (see Figure 2.1). This conceptualisation supports Callaghan et al’s (2015) idea that children should not be seen as passive in the context of coercive control, and suggests children may become directly involved in abuse by seeking help or intervening. In some examples, Mullender and her colleagues found children would climb through windows to get to their parent or siblings to intervene or seek help. Similarly, SafeLives’ Insights data (2017b) found that 30 per cent of children intervened directly and 8 per cent sought help by calling the emergency services. As discussed in previous sections, whether a child directly intervenes in the abuse, seeks help for the non-abusive parent or overhears abuse, they will be affected. It is vital that assessments consider the risk attached to each of these roles, particularly in light of the example provided by Mullender et al (2002) in which children are engaging in dangerous behaviours (climbing through windows) to protect their non-abusive parent. Working with children to develop safety plans has been shown to make children feel more empowered and may a useful consideration in the context of contact.

2.3 Children and young people’s experiences of coercive and controlling behaviour

The literature is limited in terms of how children with lived experience of domestic abuse actually experience the abuse. Those limitations are even more apparent in relation to how children experience coercive control (Callaghan et al, 2015). In this section, we explore what literature there is to understand how coercive control within the family is experienced by children and young people.

2.3.1 Awareness of the perpetrator’s use of coercive control

There is some evidence that children are aware of the coercive and controlling behaviours perpetrators use against the non-abusing parent. The Understanding Agency and Resistance Strategies (UNARS) study explored the views and experiences of young people (Callaghan and Alexander, 2015). The project involved interviews with 110 children across four European countries: Greece, Spain, Italy and the UK. Children demonstrated an understanding of the patterns of abuse and control that existed within their home. One young person in the UK described his awareness of his father’s use of control over his mother, stating that the father would not allow the mother to go out of the house to see friends (Callaghan et al, 2015). He recalled how the perpetrator would either say he needed the mother’s help (eg, to clean or cook a meal) or would resort to violence by throwing things at her. This demonstrates children’s capacity to understand the nuances of coercive control. In this example the young person was aware of the tactics the perpetrator would use to control, as well as the resulting effects (eg, his mother not going out).

Callaghan et al (2015) found children have a sophisticated understanding of control dynamics, as well as an understanding of the impact of such behaviours. For example, children recognised that subtle controlling behaviours, such as a perpetrator’s desire to know all aspects of family activity, were used to prohibit both the non-abusing parent’s and their own space for action. In one example, a young person explained how his father would ‘do things to scare us’ if he did not feel he was aware of what everyone in the family was doing. The young person explained this would be to prevent him, his siblings and his mother from going out. This example highlights how coercive control from perpetrators will also often directly impact on children within the family, and that children are often aware of this and try to operate within the unreasonable boundaries set by perpetrators.

In Callaghan et al’s (2015) study, children are also aware of and explain how perpetrators continue to control the family following separation. In one instance, a child explained his father’s use of gifts to manipulate him into sharing information about his non-abusive parent. He described how the perpetrator would either ignore him or ‘be like … oh come on, I’ll get you something’ when he wanted the child to tell him about what the non-abusive parent had been doing. In another example, a child explained how the perpetrator would wait or be present in locations where he knew the victim and the children would be, such as the shop. The child in this case recognised that this was not a coincidence but a deliberate tactic of the perpetrator to reinforce his presence. Both of these examples highlight the awareness children have of coercive control in the family, and the impact it has on themselves and family life.

2.3.2 Being used as a pawn

A common feature in terms of children’s experience of coercive control within the family is their experience of being used as a pawn by the perpetrator. As Bancroft and Silverman (2002) explained in their study, even seemingly positive behaviour from the perpetrator may in fact arise from the perpetrator’s view of the child as a ‘trophy’ or instrument in the control of the victim. It is therefore understandable within this context that children will be used as pawns. Callaghan et al (2015) found examples of abusive partners trying to involve children in hurting the adult victim, either emotionally or physically, or encouraging children to act as an informant about the non-abusive parent. Thiara and Gill (2012) also report examples of perpetrators encouraging children to hit their mother.

One child, who was encouraged to lie about an argument to undermine the non-abusive parent, discussed how this changed his view of the perpetrator from being a ‘nice guy’ to a ‘really bad person’ (Callaghan et al, 2015). This shows how aware children are of being used as a pawn to further control their non-abusive parent. In a separate example, one boy discussed how the perpetrator would use information and knowledge he provided to control the victim. This included information about who the victim had spoken to or where she had been.

Children’s perception of being used as pawns provides some useful insight. In the previously mentioned example, the child discussed how aware he was of the power he possessed as the one with knowledge and information to share, while the perpetrator was in a weaker position of wanting the information. Although children are sometimes used as pawns, this demonstrates that some are aware of this and a small number may even resist such coercive control. We explore how young people may resist coercive control in Section 2.5. An important point in relation to young people’s perceptions, however, is the level of risk perpetrators may pose to them. As discussed earlier (see Section 1.4), there are clear links between coercive control and domestic abuse and various forms of child abuse, including physical violence. Therefore professionals should be aware of the potential for violence if children resist control.

2.3.3 Managing coercive control

As SafeLives Insights data (2017b) demonstrates, a number of children become involved in trying to manage the ways in which the perpetrator will seek to control the non-abusing parent and family unit, with 30 per cent intervening and 8 per cent calling emergency services. Callaghan et al (2015) also found children reported how they would disclose to others and seek help in an attempt to manage coercive control. One child discussed calling her grandmother for assistance when she was concerned. In that example the authors describe the child’s central role in securing her family’s safety.

There are also more subtle ways in which children will seek to manage a perpetrator’s behaviour. One child recounted refusing money and gifts from the perpetrator because they knew there would be strings attached that would involve their support in controlling their non-abusive parent: ‘I’m not going to like try to be buyed’ (Callaghan et al, 2015). Recognising the behaviour as intended to control the non-abusive parent and actively resisting it demonstrates the protective role some children play within families where there is coercive control. Other children describe managing their own safety by removing themselves from the room or home when physical violence was taking place.

2.4 The impact on children and young people

This section will explore the literature base with regard to the impact of coercive control. We know that living in a climate of ongoing fear and controlling behaviour is likely to have a negative impact on children’s health and development (Radford, 2011b). Overall, however, in the current literature the voices of children who have lived in households where there is coercive control are limited. But there is research in relation to the wider impacts of domestic abuse and the types of behaviours a perpetrator may exhibit, some of which overlap with coercive control.

Practice Direction 12J on the impact of domestic abuse on children

‘Domestic abuse is harmful to children, and/or puts children at risk of harm, whether they are subjected to domestic