Building a quality culture in child and family services: Strategic Briefing (2018)

Introduction

At the highest level the statement that 'quality matters' is unarguable:

- Children and young people deserve good quality services. Quality in the children’s services world means making a positive difference, changing and improving lives.

- Making that difference motivates staff and managers. This can help with recruitment and retention and provide the organisational tone and culture likely to support strengths-based working.

- It is important to be accountable for spending public money well. Making the best use of the available resources to provide the most cost-effective services at the right quality is essential.

Nevertheless, as Forrester reminds us, quality and impact are not achieved simply by working hard.

Forrester (2016)

Positive change is supported through understanding what we are doing, reflecting on why we are doing it and how it might be done better.

Drawing on sector knowledge gathered through quality assurance (QA) workshops and examples of local authorities, this briefing offers a strategic overview and practical guidance on how an effective QA framework can support achieving the right outcomes for children and young people, and improve the quality of practice. It sets QA in the wider context of the drivers and enablers, including strengths and relationship-based practice with children and young people.

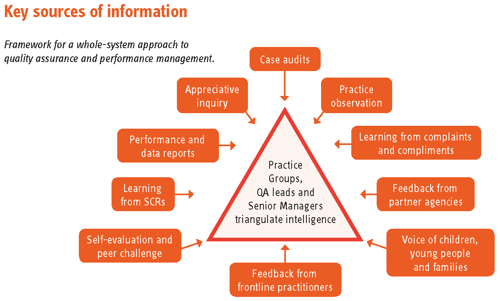

Continuous improvement - learning systems

QA is often expressed as a continuous improvement cycle (as in the graphic below) using a range of interdependent methods to measure prevalence, monitor practice, listen to people’s experiences, identify areas for improvement and enact change as a result. An effective model will identify both ‘what is working well and why’ and ‘what we need to do better’.

Ofsted, City of London (2016)

Chard and Ayre (2010)

QA has a problematic history in children’s services. ‘New public management’ (Hood, 1991), the approach that dominated public service delivery in the 1980s and 1990s, transposed market systems and management practices onto public sector delivery.

While the aspirations for accountability and transparency were perfectly rational, target-setting, auditing and inspection resulted in a system critiqued by Munro (2004) and others as process heavy, overly bureaucratic and ineffective in providing the kind of information that could contribute to improving the quality of practice. Core issues identified by Munro remain highly relevant:

- The most readily measured sources of audit came to be given undue weight in comparison to the (much less easy to measure) relational dimensions of practice, leading to ‘a distortion of the priorities of practice [in which]… the emotional dimensions and intellectual nuances of reasoning are undervalued in comparison with simple data about service processes such as time to complete a form’ (Munro, 2011).

- It remains a risk that, where organisations lack clear measures for relating inputs to outputs ‘the audit of efficiency and effectiveness is in fact a process of defining and operationalising measures of performance for the audited entity. In short, the efficiency and effectiveness of organisations is not so much verified as constructed around the audit process itself’ (Power, 1997, in Munro, 2004).

The aspiration of ‘learning organisations’ in the 21st century is to develop QA as a shared, whole-system task across wider children’s services, with the focused QA of social work practice informed by professional expertise and involving practitioners in analysing the quality of practice. Compliance with statutory requirements is an essential baseline but is far from the end game in a system committed to continuous improvement.

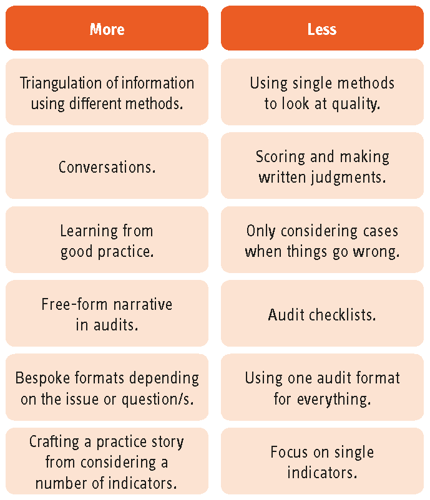

A change in approach requires changes in how methods are used. Some examples are provided in the table below and explored later in this briefing.

Sector led improvement (SLI)

Gallimore (2017)

The 2018 framework for the Inspection of Local Authority Children’s Services (Ofsted, 2017) includes an annual self- evaluation of social work practice which was developed in conjunction with the Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS), The Society of Local Authority Chief Executives (SOLACE) and the Local Government Association (LGA). This requires organisations to critically evaluate their own performance with a focus on three questions:

- What do you know about the quality and impact of social work practice in your local authority?

- How do you know it?

- What are your plans for the next 12 months to maintain or improve practice?

Alongside this ‘more grown up and proportionate inspection regime’ (Gallimore, 2017) regional sector-led improvement is developing further with emerging Regional Improvement Alliances (RIA) offering peer support and challenge, agreeing local improvement priorities and sharing best practice, including regional approaches to QA. Three regions (Eastern, West Midlands and East Midlands) piloted RIAs in late 2017 with the intention that they will become ‘the backbone of the new improvement system’ in every region from 2018.

Building a quality assurance framework

As Brooks and Holmes (2014) outlined in their review of SLI as a lever for evidence-informed practice ‘the evidence required to meaningfully undertake self-assessment is diverse and exceeds the statistical performance data traditionally used by local authority children’s services’.

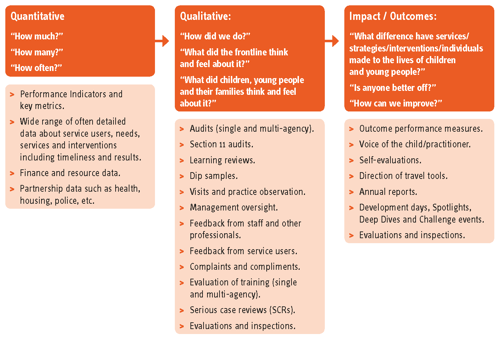

QA involves promoting critical thinking and encouraging professional curiosity to understand ‘what does this tell us?’, ‘what might this feel like to children and young people?’ and ‘what else do we need to know?’. This requires a range of methods:

- Quantitative reviews of data are a means of indirect QA (rather than a direct examination of practice), most often focused on monitoring compliance through process measures. Research and practice collaborations are testing new datasets as meaningful outcome measures for monitoring the impact of children’s services activities. Since ‘not everything that counts can be counted’, data must be analysed in combination with qualitative analysis.

- Qualitative analysis of written records, observation of practice and feedback from children, families and young people - there is potential here to build our understanding of what quality is, through engaging with research findings into practice itself (such as the ethnographic work of Ferguson (2016a, b, c)). Meaningful, rights-based collaboration offers opportunities to build practice focused on ‘doing with’ rather than ‘doing to’ children, young people and families.

This briefing is not an exhaustive guide to all aspects of QA, but focuses on some key activities. It is vital to triangulate a range of evidence to draw conclusions, and to consider the relative weightings of different sources and moderation processes to review individual interpretations.

Methods of structured enquiry

Two useful methods which allow practitioners to articulate and share knowledge, and to review local knowledge in light of research evidence:

1) Systems approach to learning

Merritt and Helmreich (1996)

We often initiate learning reviews following serious incidents and focus on proximate causes rather than examining the system as whole. A systems approach to learning from adverse outcomes draws on methodologies developed in the airline safety industry and is adapted for learning from serious incidents in health and social care. This recognises that ‘active failures’ occur in a context which arises out of ‘latent failures’ in the system. The aim is to identify factors that support good practice or factors that create an environment in which active failures are more likely, and how to prevent or reduce them (see Peter Sidebotham explain systems methodology at www.seriouscasereviews.rip.org.uk).

- Recognise that poor practice will happen and needs to be identified as early as possible so that it can be corrected or reduced.

- Develop a QA culture which encourages everyone to speak up or identify emerging problems at an early stage.

2) Appreciative inquiry (AI)

Appreciative Inquiry is an important methodological lens to keep in mind in a system that is more geared to responding to ‘failures’, mistakes or tragedies. This creative approach focusses on what has gone well and how to build on those strengths. AI does not replace other methods of enquiry, QA and evaluation but complements them by asking questions that focus on what works and ideas for what could be better.

- Encourage recording good practice during self-assessments and audits.

- Share examples of good practice through team meetings, learning circles, e-bulletins.

- Use case studies and quotes from case recordings which illustrate good practice.

- Provide opportunities for children, young people and families to feedback on where things have worked well.

See the Research in Practice resource Appreciative Inquiry in child protection - identifying and promoting good practice and creating a learning culture: Practice Tool (Martins, 2014): www.rip.org.uk/appreciative-inquiry

Core elements of a quality assurance framework

Principles and purpose

In a practice system where there is clarity about the purpose of roles, processes and activities, the ‘why’ of undertaking QA activities will make the link directly back to this purpose.

Leeds City Council works within a Restorative Practice framework and set out the principles and purpose of their QA framework as follows:

- Child-centred

The focus of quality assurance will be on the experiences, progress and outcomes of the child or young person on their journey through our social work and safeguarding systems. - Restorative

Quality assurance will be restorative. Instead of a top-down approach, quality assurance work will be based on working with staff and managers and building relationships. As a restorative process quality assurance will be characterised by both high support and high challenge. - Outcomes-based

In line with the key behaviours for children’s services, the proper focus of quality assurance will be on outcomes rather than processes. - Positive

Our approach to quality assurance will be positive - looking at informing and encouraging improvement, and supporting the development of staff and services. - Reflective

Our quality assurance framework is designed to be about promoting reflective practice and shared learning.

www.leedschildcare.proceduresonline.com/chapters/p_quality_ass_frwork.html

Practice standards

Informed by national professional guidance and legislation, social work principles and standards of proficiency, and drawing on sources such as the Professional Capabilities Framework, the Knowledge and Skills Statements for child and family social work, as well as practice frameworks used in your organisation.

Children, young people and families at its heart

Leeds Council (2012)

An excellent starting point for setting quality standards is to ask children and young people what is important to them. Quality can be articulated through capturing children and young people’s requirements of a service. The measure of quality will then be in the satisfying of these requirements. There are consistent messages from research about basic standards for working with children and young people which can be monitored through a range of QA activities, such as: workers skilled at listening and demonstrating an understanding of what is important to children and young people; professionals turning up to meetings and appointments on time; having one person who coordinates things and that person doing what they say they will do; not having to tell sometimes painful stories over and over again; and knowing who does what and where to go for help.

- Ensure datasets include indicators which monitor children and young people’s participation.

- Work with an intention to ‘walk in the shoes’ of the child, to see and feel their experiences. Ask yourself and your colleagues to reflect honestly on whether what you are providing ‘would be good enough for my child?’.

- Involve children, young people and families in defining what quality is and in the QA process itself. Consider how the perspectives of children and young people are included in any method of QA being used. North East Lincolnshire’s Voice of the Child Tools enable a consistent approach to capturing the voice of children and young people from 0 to 18, with a range of forms for children and young people at different ages and developmental stages: www.nelsafeguardingchildrenboard.co.uk/practitioners

- Make use of participation activities already underway. See, for example, Islington’s Children’s Active Involvement Service: http://directory.islington.gov.uk/kb5/islington/directory/service.page?id=wqtGCAQU_Dk

There is also Hampshire’s ‘SPARK’ website for looked after children and care leavers:

www.hotboxstudios.co.uk/web-design/hampshire-county- council-spark-umbraco-web-design - Think beyond surveys and work with children and young people on more child-led means to capture their voices.

- Engage technology. The Mind of My Own (MOMO) self- advocacy app for mobile phones includes a version for younger or learning disabled children and a ‘Service MOMO’ to aggregate app activities into performance reports and thematic data charts: www.mindofmyown.org.uk

- Always give feedback to children, young people and families who have been involved, sometimes referred to as ‘you said, we did’ feedback.

- Draw on national initiatives, such as Participation Works’ Young Inspectors: www.participationworks.org.uk/topics/young-inspectors or the Young People’s Family Justice Board which undertakes reviews of family courts and contact centres: www.cafcass.gov.uk/family-justice-young-peoples-board

- See the Research in Practice resource Voice of the child: Evidence Review (Ivory M (ed), 2015): www.rip.org.uk/voice-of-the-child

Ofsted, North Lincolnshire (2017)

Quality assurance through qualitative methods

Senior management engagement with practice builds credible leadership and develops practitioners’ confidence in talking through the strengths and weaknesses of case work as inspectors require them to do. Joining the dots: Effective leadership of children’s services drew examples from nine local authorities (Ofsted, 2015): https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/effective-leadership-of-childrens-services-joining-the-dots

- Practice weeks at Kensington and Chelsea: The leadership team undertake team audits, practice observations and conversations with families which are followed up with verbal and written feedback exploring themes, systemic issues and identifying actions to be taken.

- Deep dives in Redbridge: The performance board commissions a programme to explore areas for improvement. For instance, an audit of child protection plans led to a deep dive into how child protection conferences might enable outcome-focused plans and the ‘strengthening families’ conference methodology was explored and introduced. This resulted in significantly improved parental engagement and understanding of the risks for their child.

- Peer inspection in Hampshire: Each district was inspected at short notice by staff from all levels of the organisation, including care ambassadors - focusing on the question ‘So what difference has been made?’. The peer inspections promote transparency of practice and enable managers to get actively involved in individual cases, facilitating shared knowledge and credible leadership.

- Reflective group supervision in Redbridge: Brought together Newly Qualified Social Workers (NQSWs), social workers, QA officers and Independent Reviewing Officers (IROs) and facilitated by the Principal Social Worker, the head of commissioning, quality and finance, and a psychiatric social work manager. The aim was to:

- Provide a learning tool for complex cases.

- Explore case drift.

- Examine social work values and how they operate in practice.

- Analyse the effects of projection, transference and counter transference in relationships between social workers and those with whom they work.

- Develop effective and imaginative practice.

- Raise awareness of the self in practice, building on and improving social work resilience and effectiveness.

Practice observation

Wilkins and Antonopoulou (2017)

Observation can get to the heart of social work practice in the family home. Observation of meetings, such as child protection conferences, can support the assessment of multi-agency working, the quality of leadership by social work staff and the involvement of children and families. Specific issues to assess at observation can be informed by appraisal priorities and, in turn, observation findings will be a key source of information for staff appraisals.

- See Leeds’ Staff Observation form: http://leedschildcare.proceduresonline.com/chapters/p_quality_ass_frwork.html#observation

- Holmes and Ruch’s (2015) Evidence Scope Regarding the use of practice observation methods as part of the assessment of social work practice considers why practice observation matters, how it is applied in social work and what social work might learn from other professions.

- A Research in Practice briefing for TACT (Wheeler, 2017) focused on the practice observation element of the emerging National Assessment and Accreditation System (NAAS) and highlights role-play, observation and reflexive discussion as methods for assessing practitioner capability and aiding learning and development.

- Wilkins and Antonopoulou’s (2017) article explores issues that challenged a large programme of practice observation across three London boroughs in the context of a Wave One Innovation Programme project. Reflections on the concerns that hindered practice observation were grouped under three themes (see below).

A summary of the reasons given by social workers and managers to explain their reluctance to engage in observations of practice (Wilkins and Antonopoulou, 2017):

Concerns about the family

- Taking part in observations may be harmful for some families.

- Observations may damage the relationship between the family and the social worker.

- Families may feel under pressure to take part because of the power imbalance with the social worker.

- Families may say no to being observed.

Concerns about being observed

- Observations focus on only a small part of what social workers do.

- The home visit may go badly.

- Being observed is only suitable for students and less experienced social workers.

Concerns about being the observer

- Lack of expertise or formal authority to provide meaningful feedback.

- Tension between being a practitioner/manager and an observer/coach.

- Lack of clarity/knowledge about what good practice looks like.

- Observations as a separate activity are unnecessary because practitioners are observed frequently already.

Key messages from this article include:

- A framework for practice observations should include a description of which aspects of practice are being observed and an acknowledgement of, and sensitivity about, the context. What are you looking for, why and how will you know when you see it?

- Social workers need to be supported in understanding the value of observations and what they will be used for (for example, to inform personal or service development) and what they will not be used for (for example, performance management).

- Clarity about the role of the observer and the purpose of and basis for the observations is key. What authority and expertise does the observer have? How does their role as observer relate to the individual being observed and to the wider organisation?

- Ensure those doing the observations have sufficient authority and expertise. Provide a training and development programme for observers to help them feel confident in the role.

Case file audit

(Lincoln, 2017)

http://adcs.org.uk/assets/documentation/ILACS_NCAS_presentation_October_2017.pdf

Case files are a rich source of information about the presenting needs and services provided, quality of practice, case recording, management support and the views, experiences and outcomes of the child. If the organisational practice framework endorses strengths-based, relationship-based practice you will want to see this reflected in the terminology used and the approaches described.

Reflect on the organisational approach to audit and to sharing the findings. Are staff and managers using these as a means to promote professional curiosity and debate? Are findings being triangulated with other evidence sources?

The challenge is to move away from an overly onerous audit process focused on the ‘marking’ of individual case recording and practice and towards the drawing out of practice themes, ideally with a focus on practice in real time, rather than retrospective analysis. As Andrew Webb pointed out:

Webb (2017)

‘Beyond Auditing’ is an approach used in Rotherham that involves auditors working with social workers and team managers ‘in real time’ to provide coaching and a reflective conversation to address identified practice issues. At least two cycles of auditing a year aim to ensure that remedial action is completed without delay. Themes and issues are fed back into the culture of continual learning and can be evaluated in subsequent ‘deep dives’ to improve overall practice.

- Provide clear templates for recording that link the audit back to practice principles, standards and frameworks.

- Audit formats can be very different. Which format will work best depends on why this method has been selected and the issues being explored. For example, a list of ten to twenty timescales and processes asking the auditor to tick yes/no – a compliance check where clear judgments are made.

- A template with space for free narrative on two or three questions asking, for example, whether the case work includes the voice of the child and young person, whether professional curiosity is demonstrated or whether a positive difference is being made - focusing on the quality of the case work which would be good for promoting conversations.

- A template noting 15 to 20 standards asking for a judgement of some sort on whether this standard is met with room for free-narrative response – a mix of compliance and quality.

- Include feedback from service users to inform the case file audit and judgements about quality of practice and impact of work undertaken.

- Follow up with a shared reflective discussion with the worker on the case and aggregate learning from case audits to share more widely across the service.

- Draw on research findings on case file analysis (such as Laird et al, 2017).

Leeds use an approach for case file auditing modelled on the documents used by Ofsted inspectors: http://leedschildcare.proceduresonline.com/chapters/p_quality_ass_frwork.html#audits

Thematic audit and ‘dip sampling’: Focus on specific issues and draw on research and other evidence to inform the assessment of local practice.

- See, for example, Suffolk Safeguarding Children Board’s thematic audit on elective home education: http://www.suffolkscb.org.uk/working-with-children/thematic-audits/

- North East Lincolnshire presents one-page summary versions of findings from thematic audits, see for instance its key messages on missing: www.nelsafeguardingchildrenboard.co.uk/data/uploads/quality-assurance-and-performance/missing.pdf

- Use Ofsted evaluation criteria and research evidence to inform five to ten key elements of good practice.

- Use a simple self-assessment pro-forma which asks for feedback on strengths and areas for development or what’s working well and what are you worried about.

Supervision audit: Supervision is a fundamental means of quality assuring practice. QA of supervision itself helps identify variability in the quality and regularity of supervision and management oversight. Leeds’ framework assesses the quality of supervision against key areas identified in national research:

- Organisation and recording.

- Quality of relationship.

- Task assistance and access to services.

- Social and emotional support.

- Reflective practice.

- Impact on practice.

http://leedschildcare.proceduresonline.com/chapters/p_quality_ass_frwork.html#supervision

Quality assurance through quantitative methods

Effective use of data and performance indicators are essential elements in achieving a better understanding of practice and practice systems. Performance indicators do only indicate, often through a single statistic.

Munro (2011)

It is vital that data, practice and QA leads come together to reflect on how data are being organised, to devise means to ensure evidence is being triangulated effectively and used as a vehicle for professional debate. One challenge here is the paucity of specialist analysts to help shape, link and present local data in more meaningful ways to measure ‘How well are we doing?’ from child to organisational level. In times of reducing resources, having the right information, of a good quality, at the right time, to help leaders draw the right conclusions about performance and improvement is imperative.

Ofsted, City of London (2016)

Selecting and organising data

Effective organisations will be drawing a range of data from across the system to triangulate with other evidence. The Department for Education (DfE) Children’s Safeguarding Performance Information Framework (2015) sets out the key nationally collected data intended to ‘help those involved in child protection at both the local and national levels understand the health of the child protection system’, whilst acknowledging that ‘national level performance information can only provide part of the picture’. Local activity, such as the Local Safeguarding Children’s Board (LSCB) datasets, are therefore essential. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/childrens-safeguarding-performance-information-framework

An Innovation Programme thematic report, Informing better decisions through use of data in children’s social care (Sebba et al, 2017), recommends the development of a common framework of indicators for measuring outcomes of children’s social care services. The report flags the work of the Family Safeguarding Hertfordshire partnership to build a Key Performance Indicator dataset and includes data on police involvement, emergency hospital admissions, school attendance, substance misuse and mental health service use, as well as the most common children’s social care indicators. https://springconsortium.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Thematic-Report-5-FINAL-v1.pdf

The report recommends shaping a Theory of Change to clarify what a service or practice is intended to achieve, the intermediate and long-term outcomes that might be expected and how these will be measured. Nesta’s guidance on developing a Theory of Change is signposted with hyperlinks to standardised measures that might be used to monitor specific outcomes. https://www.nesta.org.uk/sites/default/files/theory_of_change_guidance_for_applicants_.pdf

So, an outcome of ‘improving the quality of relationships between young people and parents/carers/social workers’ might be monitored using Pianta’s Child-Parent Relationship Scale: https://curry.virginia.edu/uploads/resourceLibrary/CPRS.doc

The Stability Index is an initiative by the Children’s Commissioner to measure the stability of the lives of children in care by measuring three aspects of children’s experiences - placement moves, school moves and changes in social worker. www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/publication/stability-index-initial-findings-and-technical-report

A traditional balanced scorecard approach provides a view on organisational performance from four perspectives:

Financial

- Including cost and value for money.

Customer

- Indicators which demonstrate participation and focus on processes and outcomes which are important to children, young people and families.

Internal business processes

- The key statutory processes - including quantity, quality and timeliness.

Learning and growth

- Workforce (quantity, skills and workforce development).

(Adapted from Kaplan and Norton, 1996)

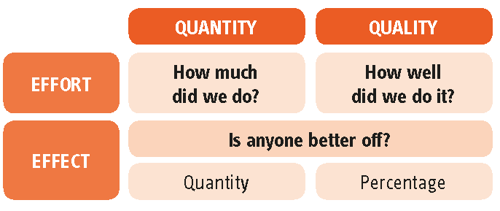

Mark Friedman’s Outcomes-Based Accountability (OBA) proposes that indicators are grouped around three key questions:

Improving the quality of relationships between young people and their peers might use the Harter Self-Perception Profile: www.portfolio.du.edu/SusanHarter/page/44210 or the Friendship Quality Questionnaire: http://www.midss.org/mcgill-friendship-questionnairefriendship- functions.

Friedman observed that ‘data tend to run in herds. If one indicator is going in the right direction, usually others are as well’ and that some measures are ‘bellwethers’, in that an improvement might lead to an improvement in other areas (Friedman, 2005 - see www.resultsaccountability.com).

A longstanding tool in the sector, the OBA model was used in several projects in Wave One of the DfE Innovation Programme as a way of structuring planning to improve outcomes (for example, Laird et al, 2017).

Models which consider social return on investment estimate outcomes in terms of economic, social and environmental value (see the Cabinet Office, 2012).

Data visualisation to support professional debate

Finding ways to make data more accessible is an important aspect of engaging practice leads and practitioners in the QA process.

ChAT was developed to provide all local authorities with benchmark information around the Ofsted Annex A dataset, as part of a collaborative project between Waltham Forest Council, Hackney Council, Tower Hamlets Council and Ofsted. It is available to all local authorities at: www.khub.net/web/chat-childrens-services-analysis-tool

See Waltham Forest’s NCAS presentation for more detail:

www.adcs.org.uk/assets/documentation/AC17_Fri_E_www.pdf

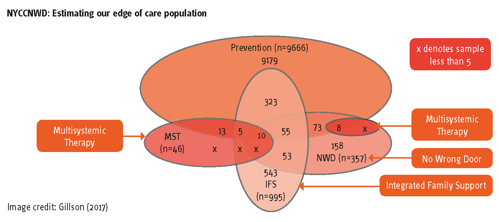

In the course of their Innovation Programme project, North Yorkshire County Council No Wrong Door (NYCCNWD), North Yorkshire made great use of the expertise and capacity of an embedded data analyst working with the evaluation team from the Centre for Child and Family Research at Loughborough University. They developed a tool to enable longitudinal analysis of the needs, services and outcomes of children and young people on the edge of care (Lushey et al, 2017) which drew on previous work on a Cost Calculator for Children’s Services (Holmes and McDermid, 2012; Ward, Holmes and Soper, 2008). This team then joined forces with Research in Practice and a group of data, finance and service leads from 19 local authorities to develop this work for use beyond NYCCNWD: www.gov.uk/government/publications/no-wrong-door-innovation-programme-evaluation

A 2017 presentation by Research in Practice, North Yorkshire County Council and Loughborough University includes animations from NYCCNWD which visualise data to improve understanding of its ‘edge of care’ population (see below example): https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/ WT22.%20RiP.%20Edge%20of%20care%20-%20needs,%20 services,%20costs%20and%20outcomes%20-%20 Susannah%20Bowyer,%20Lisa%20Holmes%20and%20 David%20Gillson.pdf

Needs assessments, spotlights and profiles: Tools to bring together a range of evidence on specific issues

Bringing together the range of evidence gathered through these elements is essential to be able to draw a more robust view of ‘How well are we doing?’. This includes opportunities for analysing and discussing qualitative and quantitative information which involves a range of stakeholders and which look across services at the journey of the child. Holding ‘spotlight’ events on specific themes, conducting needs assessments or profiles, annual reports or learning events are all methods to achieve this.

A profile will require collective ownership across all partners to support its development and a committed and effective analyst to review key findings and identify intelligence gaps (OCC, 2013a; LGA, 2014). A recent Research in Practice Evidence Scope on Working Effectively to Address Child Sexual Exploitation (Eaton and Holmes, 2017) suggests profiling should:

- Bring together all known intelligence and relevant data held across different agencies to inform strategic decision-making and local practice development.

- Have clear terms of reference and a clear plan for data collection formulated for each agency detailing what is required from them.

- Include third sector and voluntary sector organisations as well as statutory and non-statutory public sector organisations.

- Identify intelligence gaps.

- Help to identify the known extent of the problem and identify where resources should be targeted.

Ofsted, Kensington and Chelsea (2016)

Aim to draw the learning from QA together with other evidence in compelling formats with bites of statistical data laid out in accessible design, descriptions of activities and the delivery underpinning those activities and reflective reporting on progress.

Cafcass’ Quality Account is one example:

www.cafcass.gov.uk/about-cafcass/reports-and-strategies

Keep communicating why quality matters

We hope this briefing will help strategic leaders build mixed methods QA processes that lead away from ‘shallow rituals of verification at the expense of other forms of organisational intelligence’ (Power, 1997) and towards an environment ‘in which social workers feel supported, challenged, valued and encouraged [and] positive and constructive challenge is encouraged’ (Schooling, 2016); and in which listening to children and young people is at the heart of setting and understanding quality.

Quality assurance top ten tips

1. Be clear what good QA activity looks like, and ask:

- How accessible and easy to read is the QA framework? Can it be summed up pictorially for staff? What do they understand about it, and their part in it?

- Is it professionally led and social work friendly, and is QA at the forefront of practice and driving the practice narrative?

- Are audit and other QA tools and methods effective? QA is more than audit.

- Are all staff clear what good practice looks like? Do we have practice standards and are staff able to access processes and tools to support effective practice? Knowing what good looks like is critical, but it should not be complicated.

- Do we measure quality of practice as well as what is right/ wrong in the system (compliance)? Is there an overemphasis on describing risk rather than a focus on need?

2. Ensure it is embedded throughout the organisation with QA activity at the right level:

- Don’t forget to include fostering, adoption and commissioned services in audits and QA.

- What role are your DCS and strategic leads playing? Your PSW?

- Ensure there is time for writing up, following up, reflection and action planning - ‘double loop learning’.

3. Do ‘with’, not ‘to’:

- How are you ensuring staff are part of QA activity, and working out ways to support them to view QA as a learning tool, not a stick?

4. Keep on with the ‘routine’ audits but consider the value of well-placed thematic audits:

- Thematic audits across a local area or services shine a light on specific areas of practice or needs, especially when combined with data and ‘the voice’. Common areas at present for local authorities to focus on include step up/step down and the Public Law Outline (PLO).

5. Ensure there is a strong voice included in QA:

- Triangulating results of case file audits or other QA activity with feedback from children, families, staff and other professionals provides a much richer picture of what life has been like for the child and the quality of practice. Ensure feedback is a routine part of case audits and think about what weight it has. Quality of feedback should be considered alongside quantity of feedback.

6. Aim high:

- QA activity should not just be about identification and resolution of ‘inadequate’ or ‘requires improvement’ audits and where quality of practice is below standard, but also at how practice can be continuously improved.

7. Understand what has made the difference in this case(s):

- Do we know what has led to the (good) quality of practice – which interventions, factors or behaviours have contributed to this outcome for the child(ren) in this instance? What is it that has made an impact and can that be shared or replicated?

8. Discussions about quality of practice and learning from audits should be an integral part of regular performance discussions and learning:

- For example, in Performance Boards, alongside scorecards, reports, workforce development. Summary audit reports should focus a small proportion on the mechanics (how many audits completed, sample, etc) and a large proportion on the findings and learning – what have the audits told us about quality of practice?

- Consider how your audits reflect how well the auditor knows/ uses the client records system - but, also, what are we learning from audits about what training on the system may be required? Ofsted will sit live with the worker on inspection, and there is an expectation they will be able to navigate comfortably around their case record.

- How are you sharing the learning with partners?

9. Be honest and balanced – celebrate success and identify what needs to be better:

- Recognise that not all outcomes are good – that’s ok if you learn from them and evidence what you are doing to improve and when you will have achieved it. Ofsted is expecting honest self-evaluation, rather than “everything is rosy”.

- Consider using a reflective tool(s) for social worker feedback - asking practitioners what they have done well, what didn’t go well, what helped them (tools, etc) and what they would do next time.

10. Use it effectively to generate continuous improvement:

- Is the learning shared linked to plans? Ensure it is fed into service planning and workforce development.

- Consider setting up mini action plan task and finish groups to fix things quickly that may be emerging from learning.

- Learning may entail big culture shifts for teams, and may take time - revisit and check the direction of travel regularly.

Brooks and Lincoln for Eastern Region ADCS (2018)

Professional Standards

PQS:KSS - Organisational context | Promote and govern excellent practice | Shaping and influencing the practice system | Performance management and improvement | Lead and govern excellent practice | Creating a context for excellent practice | Designing a system to support effective practice

PCF - Contexts and organisations | Professional leadership

This publication is a premium resource

Access the full publication with a one-off purchase or enjoy the benefits of membership.