The impacts of abuse and neglect on children; and comparison of different placement options: Evidence Review (open access)

Commissioned by the Department for Education and developed by Research in Practice, this open access paper reviews research on the impacts of abuse and neglect and the strengths and weaknesses of care placement options. It is intended to support local authority and judicial decision-makers to develop a shared understanding of research and make decisions that lead to stable and positive placements for children and young people.

1. Introduction and methodology

1.1 Introduction and aims of the review

Background

In recent years the government has introduced a number of policy papers aimed at transforming the children's social care system. 1 Much of this reform began in 2000 with the publication of Adoption: A new approach. 2 More recently, major changes have been introduced through the Family Justice Review 3; the subsequent Children and Families Act 2014 4, including the revised Public Law Outline (PLO) and the 26-week timeframe for completing care proceedings; and the recent publication of Putting Children First. 5

When the Family Justice Review was launched in 2011, the average duration for the disposal of a care and supervision application was 56 weeks. The revised PLO was phased in between July and October 2013 following a year-long pilot in the tri-borough authorities in London. Since then there has been a significant reduction in the duration of care proceedings with the average (at the time of writing) being around 27 weeks. 6 There is some recent evidence to suggest that this has been achieved without delay being moved to the pre- or post-court period 7, although this finding needs to be considered in the context of how cases are being managed by local authorities before formal proceedings are issued or during the pre-proceedings stage of the PLO.

The judiciary have acted as a strong driver for the completion of cases within the 26- week timeframe. However, beneath the national average statistics, proceedings duration for individual local authorities and for local family justice board areas vary significantly. 8 These reductions in care proceedings duration have taken place in the context of increasing demand on the public family law system and changes in the use of some types of order:

- The number of care applications continues to rise. Between April 2015 and March 2016, total applications were 15 per cent higher when compared to the same period in 2014-15. And in the first six months of 2016-17, the number of care applications increased by 23 per cent over the same period in the previous year, although there was a drop in December 2016. 9

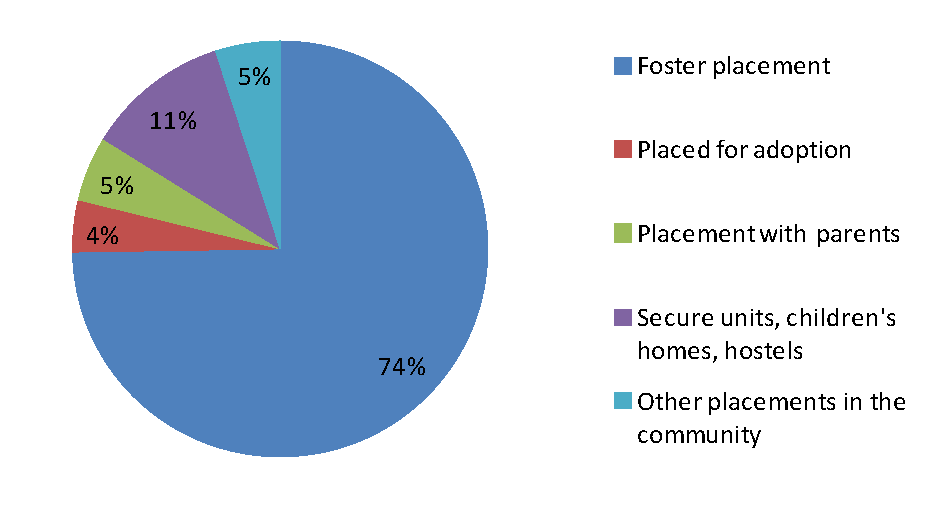

- At 31 March 2016, there were 70,440 looked after children in England, an increase of one per cent compared to 31 March 2015, and an increase of five per cent compared to 2012. 10

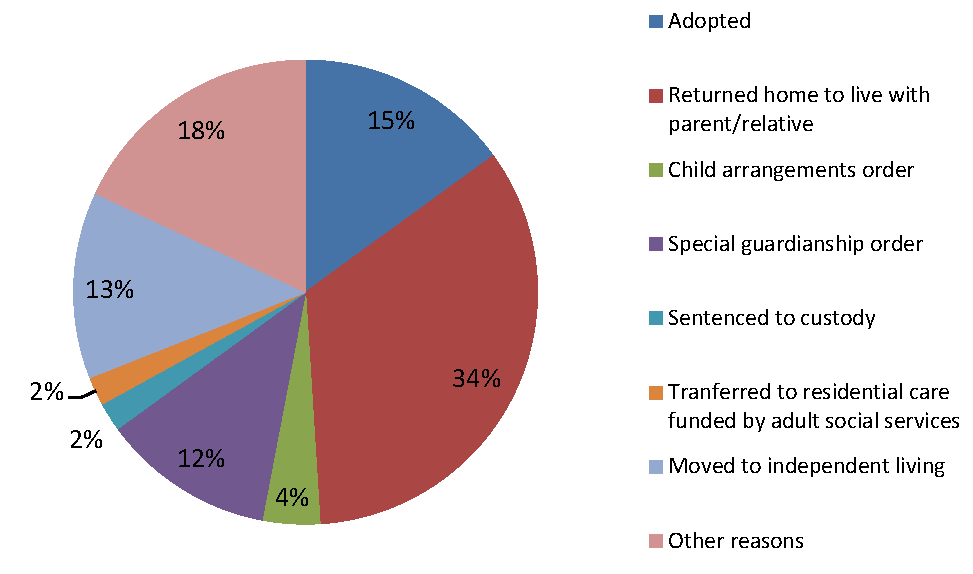

- The use of special guardianship orders (SGOs) rose from five per cent of all children ceasing to be looked after in 2010, to 12 per cent in 2015-16. 11

- Since September 2013, the number of court confirmed plans for adoption has almost halved. From 2012, adoption levels were rising and reached a peak in 2013 -14 (9,080 children placed for adoption). From September 2013 this trend reversed, a change attributed by many to the impact of Re B-S and other court judgements. 12 The number of looked after children placed for adoption fell to 7,740 in 2015-16. 13

Aims

The initial impetus for the commissioning of this evidence review was a commitment set out in Adoption: A vision for change (2016) to produce 'an independent summary of relevant research evidence for use by local authority managers, social workers and judges which focuses on comparative outcomes of different placement options'. The government made this commitment in response to several factors, including the increase in the number of children entering the care system, shifts in patterns of decision making and the ongoing aim to ensure that factors known to be crucial to children's outcomes are considered when placement decisions are made. 14

The aim of this review is to bring together a summary of key research findings in one document intended to be accessible to judicial and local authority decision makers (although this will also be of interest to others including Cafcass guardians) with regard to two key themes:

- The impacts of abuse and neglect on children

- The strengths and weaknesses of different types of long-term placements in relation to their impact on children.

The review is intended to help decision makers (including Cafcass guardians) reflect on the needs of children who have been abused or neglected and understand how different placement types may address particular needs. We hope that the work undertaken here (between October 2016 and January 2017) provides a useful summary document that will support the complex series of decisions that lead to placements that are stable and positive for the children and young people concerned. Nevertheless, it is important to manage expectations from the start. This review does not offer definitive answers on the themes noted above.

Firstly, it is important to note that research has its limitations and bodies of evidence change over time. (The limitations of this review are considered at 1.3 below.) Decision makers need access to information that is comprehensive and regularly updated; this review offers a picture at the current time. Secondly, the application of research evidence in making decisions in relation to individual cases requires learning and development support and relies on those informing the decision making to have an in-depth understanding of the individual child, their family and wider context. There are no generic answers that research can provide that can be applied in a wholesale way across the specific case circumstances of individual children, young people and families. We can learn a great deal from the aggregated evidence that research provides, but that evidence only gains meaning when it is applied, with analytical rigour and critical thinking, to each individual situation. Thirdly, whilst this review is intended to be useful to decision makers in local authorities and within the judiciary, it is recognised that colleagues working in different parts of the system will have their own professional perspectives and areas of specialist expertise. This piece of work is therefore necessarily generic in the whole, and seeks to augment the existing more specialised knowledge sources.

1.2 Methodology and scope of the review

This paper is not a systematic review. A full systematic review of the extensive and various bodies of research in relation to the themes outlined above is beyond the scope of this commission. Rather, the aim is to provide a broad and accessible overview of the most relevant research. The primary focus of the review is on key UK research from 2000 to 2016. Reference is also made to key international evidence that has particular relevance to the review.

Evidence was drawn from peer-reviewed papers that either report on, or provide a robust review of primary research in relation to the key themes, along with a small number of policy papers and independent reviews. Searches were conducted using online databases (e.g. Social Care Online; Google Scholar) and broad search terms linked to the topic areas and themes of the review (e.g. impacts of abuse and neglect; educational outcomes for looked after children; placement stability). Given the timescales of the project, the initial focus was on searching for existing research reviews in relation to the key themes, with key research studies that were identified in the literature being explored in further detail. Searches were also made of key websites and repositories of relevant research and statistics. Guidance was sought on the scope and content of the review from an expert advisory group (see Appendix 1) set up by the Department for Education. Experts on the key themes of the review were also consulted to critically appraise the content of the report.

A key challenge for this evidence review was the need to strike a balance between rigour and accessibility, without over-simplifying the evidence. Of particular importance was the need for clarity with regard to the robustness of the research and caution in attributing causality when presenting the findings. To address this, an appendix has been included which summarises the methodological approaches used in key research papers that are referred to in this report and any limitations to the findings. Given the critical importance of the decision making this review is intended to support, readers are strongly encouraged to read this appendix.

1.3 Limitations and considerations

When considering the evidence in this review it is important to bear in a mind a number of considerations.

- Research findings do not tend to identify outcomes for individual children. Children and young people who are the subject of care proceedings are all individuals with specific social, cultural, familial and genetic characteristics. All of them develop their identity within some form of family relationships and all have specific experiences and vulnerabilities. This myriad of factors can result in children and young people having differing susceptibilities and resiliencies in the face of adverse experience, so the outcomes for one child may be very different to those of another, even within the same family. 15 So, while findings from research relating to specific groups or specific outcomes are helpful in informing decisions, they cannot predict outcomes for individual children.

- There is not an equal body of literature, in scale or rigour, available in relation to each of the issues raised in this report. Some topics have benefited from high quality research whilst others are less represented in the literature. This presents challenges in offering direct comparisons between impacts of different types of harm or between types of placement.

- As with much social research, it is often extremely difficult to determine the direction of cause-effect relationships. The 'gold standard' for research in determining whether a cause-effect relationship exists is the use of a randomised controlled trial (RCT), where individuals are randomly allocated to a 'treatment' or 'control' group. RCTs minimise bias and control for extraneous factors. RCTs are rarely used in research pertaining to children's social care in England 16, partly because of the ethical issues that are raised by the random allocation of children to different placement options or therapeutic interventions or to control groups.

- As a result, other robust research designs are used. These generally include the use of comparison measures between or within groups (e.g. comparing mental health outcomes for looked after and non-looked after children) and explore statistical associations between factors thought to be linked to particular outcomes. In addition, qualitative studies are used to answer different kinds of research questions and to provide more in-depth and explanatory information (e.g. to explore the values and contextual issues that inform professional decision making or the perceptions of service users and professionals).

- Research evidence evolves over time and interacts with current policy priorities and with public consciousness and as such, does not provide fixed solutions or definitive answers for decision making at individual case level. The application of research evidence in practice requires nuanced professional judgement and sophisticated analytical skills from senior decision makers in local authorities as well as the judiciary.

- Some of the research (e.g. the evidence on neurobiology and brain functioning) is relatively recent, and the evidence base is still developing and subject to some debate. Interpreting this research for application in policy or individual case decision making brings a number of challenges. This is true for all evidence and is especially important when research is emergent. 17

- The evidence does not always distinguish between specific forms of abuse and/or neglect, which can be challenging in terms of understanding the distinctive pathways, impacts and required protective actions. It should not be assumed that broad findings are applicable to every form of harm; this review attempts to caution against this but recognises that summary reports of this nature do pose this risk.

- The evidence is sometimes lacking in terms of how specific characteristics, such as gender and ethnicity, interact with the findings on maltreatment or placement type. It is beyond the scope of this review to explore these issues.

- Neither local authority nor judicial decision making take place in a vacuum. There are a myriad of factors that inform professionals’ assessment of whether a child is at risk of significant harm and what is the most appropriate action to take in planning for the child's safety, well-being and future. The messages in this review should be understood within this. The contexts for local authority and judicial decision making are explored below.

1.4 Context for local authority and judicial decision making

The value of using theory and research findings in conjunction with other evidence to inform decision making in child protection and family court decision making has been emphasised in this field in recent years. 18 Decisions are taken at numerous points in the processes where children and families are involved with the judicial system and family courts.

Key points in local authority decision making include, for instance:

- decisions in relation to assessing and responding to the risks, vulnerabilities, protective factors of the birth family and wider network of relationships

- the approaches taken in working with a family to provide support and enable positive change

- providing temporary placements for a child at the parents' request

- complying with the requirements of the Public Law Outline

- ensuring that the child’s right to a family life is taken into account in any plan for the child

- assessing firstly the viability and then the suitability of alternative carers in the family network

- commissioning necessary specialist assessments exploring the provision of a range of alternative placement options as a part of the requirement to make a permanency plan for the child. 19

Theory and research will, implicitly and explicitly, inform professionals’ decision making throughout the child’s journey through the care system and the authority’s recommendations to the court. This may occur implicitly (without direct citation, but underpinning the knowledge and skills which inform the professional judgements made) or explicitly (where research evidence is directly cited to support the analysis made).

Behind an individual social worker’s presentation of a local authority’s recommendations in court are a plethora of other professionals in roles which influence, guide or direct decision making. These professionals commonly (but not exclusively) include: line managers and supervisors; Child Protection Conference Chair; Independent Reviewing

Officer; Legal Advisor; Case Progression Manager; Finance Manager; Head of Service or equivalent. The views of the parent(s) and child should be listened to and considered throughout the process, as should the opinions and advice of other key professionals (e.g. in health, police and education).

During court proceedings, decision making is further influenced by the Cafcass children's guardian, the parent’s lawyers, independent assessors and potentially others. Within the court arena, decision making is informed by negotiations between parties to reach an agreement that is in the best interests of the child.

Judicial decision making is framed by the bedrock principle of judicial independence. Individual judges, and the judiciary as a whole, are impartial and independent and focus on the application of the law to the individual case before them, according to the principles of justice. This ensures that those who appear before them (and the wider public) can have confidence that any decisions are made fairly and in accordance with the law. 20 Judicial independence in the family courts is enacted through each judge deciding cases solely on the balance of evidence presented to the court and according to both statute and case law. In all cases, the welfare of the child is the court's paramount concern. In order to achieve this, key issues are considered by the court:

- The Children Act 1989 requires the court to have regard to the welfare checklist set out in section 1 of the Act when it considers any questions relating to the upbringing of a child. 21

- Any decision in relation to the child is proportionate and balances the various options open to the local authority and the court.

- Under the Children Act 1989 the court is required to take the least interventionist approach. Under the Adoption and Children Act 2002, 'the court must not make any order under this Act unless it considers that making the order would be better for the child than not doing so'. Additionally, parental consent to adoption can only be dispensed with if either parent is incapable of giving consent or the child’s welfare requires this. 22

The legal context for decision making is discussed further in section 4 of this report.

1.5 The evidence review

The bodies of literature pertinent to the topics at hand in this paper are extensive (although there are still gaps in knowledge), cross a number of disciplinary fields, and are constantly being added to with newly published studies. The scope of this review does not enable a definitive summary of all of this material – which would run to several hundred pages. The following sections provide a summary of consistent findings from evidence reviews and research studies on the potential impact of abuse and neglect for children and the potential strengths and weaknesses of different placement options. Gaps in the existing evidence base are also identified.

2. Defining and identifying abuse and neglect

Key points

- Abuse and neglect can occur at different ages and stages of child and adolescent development, and for a multitude of different reasons including a variety of parental vulnerabilities.

- Children and young people's ability to rebound from such adverse experiences is related to a number of characteristics and supporting factors such as their age, family environment, social networks and the wider community.

- Neglect is the most prevalent form of maltreatment; however, it can be difficult for professionals to identify neglect and to evidence whether the threshold for statutory social work intervention and/or court action has been reached. Neglect also often occurs in the context of other factors.

- Individual, community and societal factors interact in complex ways to increase or decrease the risk and impact of maltreatment.

- There are protective factors that can be enhanced and promoted. Providing earlier, effective support to parents, whilst keeping the child's welfare in mind, can reduce the risk of maltreatment.

- Children with disabilities appear to be one group at heightened risk of experiencing maltreatment.

2.1 Safeguarding children

If there is reasonable cause to suspect that a child is suffering, or is likely to suffer, significant harm a local authority has a duty to make enquiries under section 47 of the Children Act 1989 and decide whether any action should be taken to safeguard and promote the child’s welfare .23 Local authorities need to provide factual evidence to the court in order to show that, on the balance of probabilities, a child has suffered, or is likely to suffer, significant harm. Harm is defined in the Children Act 1989 as 'ill-treatment or the impairment of health or development including, for example, impairment suffered from seeing the ill-treatment of another' (s.31(9)). Working Together (2015) 24 provides definitions of different types of harm, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect (see Appendix 2).

Child abuse and neglect are often subsumed under the umbrella term 'child maltreatment' which has been defined by the World Health Organisation as:

All forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power. 25

Whilst acknowledging that there are distinctive characteristics between abuse and neglect, the term 'maltreatment' is used throughout the report where the evidence does not distinguish between specific forms of abuse and/or neglect. Maltreatment can occur at different ages and stages of child and adolescent development.

2.2 Risk factors associated with child maltreatment

Parental vulnerabilities

There are a number of parental vulnerabilities that can have an adverse impact on parenting capacity. It would be incorrect to assume a direct causal relationship between parental vulnerabilities and children experiencing abuse and neglect; many parents who experience some of these issues raise their children safely. Nevertheless, research suggests a heightened risk of child and adolescent maltreatment, in particular where more than one of these factors co-occur, as is often the case. 26 These factors appear to interact with one another, creating cumulative levels of risk and need the more factors are present. Parental factors associated with increased risk of maltreatment of children include:

- parent's exposure to adverse experiences during childhood (e.g. parental domestic violence, substance misuse, mental health issues)

- domestic abuse, mental health difficulties, drug and alcohol misuse (combined or singly)

- a history of crime (especially for violence and sexual offences)

- patterns of multiple consecutive partners

- acrimonious separation

- parental learning disability

- intergenerational cycles of child maltreatment. 27

Where a parent has their own vulnerabilities, such as those listed above, the stresses of parenting are likely to be significantly greater. However, as mentioned, parents facing these difficulties can and do raise their children safely. Although some children who are exposed to parental mental illness, learning disability, substance misuse or domestic violence exhibit behavioural or emotional problems, others show no long-term disorders. 28 Woolgar (2013) has used the term (from developmental science) 'differential susceptibility' to explain why some children are more affected by their earlier experiences than others. It highlights differences in children's sensitivity to positive and negative environments, with some children being particularly vulnerable to relatively low levels of adversity while others are less affected by such environments.

Children’s experience of domestic violence in their home environment is recognised as a form of harm in itself. 29 The impacts of domestic violence on children differ by developmental stage, but when children experience domestic violence in addition to other forms of abuse and neglect there is understood to be a high risk of emotional and psychological harm. 30

It has been argued there is a tension between the need to keep children safe in situations where there is domestic violence and not blaming and/or punishing the non-abusing parent. As noted in a recent report by Women's Aid: 'Every point of interaction with a survivor is an opportunity for intervention. It should not be missed, and should never add to the huge barriers survivors already face … Supporting the non-abusing parent is likely to improve the safety and well-being of children and should always be fully explored.' 31

Understanding the experiences of children and young people in families where there is risk of maltreatment requires direct engagement that goes beyond seeking to understand wishes and feelings (which is itself vital). Social workers must identify and have a nuanced understanding of the daily lived experience of the child. They must also maintain a focus on individual children because similar behaviours on the part of the carer may affect individual children in the family differently 32 and, in some cases, one or more children may be treated differently or experience ‘preferential rejection’. 33

Community and societal factors

Although much of the evidence base on risk factors associated with maltreatment focuses on risks at the individual parental level, the literature also recognises the interaction between individual, community, and societal factors. A recent review of the international evidence found an association between families' socio-economic circumstances and the chances of their children experiencing maltreatment and/or of maltreatment being identified. 34

It is important to note that poverty in itself is not a sufficient factor in predicting the occurrence of maltreatment. Children whose families are not living in poverty also experience maltreatment, just as most children in families living in poverty do not experience maltreatment. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that the direct and indirect impacts of poverty interact in a complex manner with other factors that affect parenting and can increase the risk of child abuse and neglect. 35

Emerging evidence also points to significant inequalities in rates of children's services interventions, which have been found to be linked to deprivation. 36 Research based on a large longitudinal UK cohort study, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), found that poverty was a significant factor both for investigating child maltreatment and for placing children on child protection plans. Poverty also interacted with other factors in the parental background and family environments. 37 Another UK study tracing the life pathways (from birth to age eight years) of a small group of children (n =36) who were identified as likely to suffer significant harm before their first birthday also found that poverty, unemployment, poor housing, isolation, living in dangerous or hostile neighbourhoods, and parental physical and mental health problems all increased the stressors in families and made the recurrence of factors associated with child maltreatment (e.g. domestic violence, substance abuse) more likely. 38

As with parental vulnerabilities, the relationship between these community and societal factors and child maltreatment should not be understood as straightforward or causal.

2.3 Protective Factors

Individual children and young people's ability to cope with and rebound from adverse experiences is related to a number of characteristics and supporting factors. These include factors such as their age and developmental stage, the presence of resilience- promoting relationships in their lives and access to wider family support. 39 These factors can buffer children from the impact of abuse and/or neglect, and as with risk factors, they can interact with each other.

The welfare of the child is the fundamental concern for social workers and other professionals. However, in addressing the child’s welfare they must also give due attention to the needs and concerns of parents, who may themselves be vulnerable.40 A growing body of research and practice innovation advocates holistic approaches to working with families, which do not compromise the safety of the child and engage parents and wider family in change processes that may help protect their children. 41

Although protective factors have arguably not been studied as extensively or rigorously as risk factors, there is evidence that the following factors can help to protect children from the impact of maltreatment:

- Supportive family environment and social networks

- Communities that support parents

- Adequate housing

- Access to health care and social services

- Nurturing parenting skills

- Stable family relationships

- Reasonable and consistent household rules and child monitoring

- Parental employment

- Caring adults outside the family who can serve as role models or mentors

- The presence of a non-abusive partner

- Parents' recognition of the problems

- Parents' willingness to engage with services. 42

Actions to promote protective factors should be taken as early as possible. One clear premise for providing evidence-informed early help to families is to mitigate the risks of children being maltreated by addressing issues before risks escalate. Messages on effective early help suggest that this relies on reciprocal working relationships across agencies (e.g. between children’s and adult services, including mental health, drug and alcohol, and probation services) and should include ongoing, tiered packages of support (as opposed to bursts of intensive, short-term interventions followed by withdrawal of support) designed to meet the needs of individual children and their families. 43

If intervention and support does not result in sufficient change to protect children from significant harm, then escalation may be necessary. In some cases this may lead to court proceedings and for some children, it will be deemed necessary to remove them from home and into an alternative placement. 44

2.4 Prevalence of abuse and neglect

There are no definitive figures on the number of children who have experienced abuse and/or neglect. Knowledge about the scale of maltreatment in the UK comes from three specific sources:

- recorded offences

- child protection systems

- self-report studies. 45

All have their limitations and estimates vary according to the source of information, the time-period over which data are collected and the ways in which abuse and neglect are defined.

Statistics on recorded abuse and neglect are considered under-representative of children and young people’s experiences. 46 However, evidence from a large-scale 47 self-report NSPCC survey (conducted in the general population in 2009) found that neglect is the most commonly reported form of maltreatment in the family.48 The study found that ‘severe’ child maltreatment49 in the family was reported as an experience for a minority of children and young people during their childhood, as illustrated in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Rates of self-reported severe maltreatment in the family during childhood 50

|

Maltreatment type |

Under-11s |

11-17s |

18-24s |

|

Severe neglect |

3.7% |

9.8% |

9.0% |

|

Severe physical violence |

0.8% |

3.7% |

5.4% |

|

Contact sexual abuse |

0.1% |

0.1% |

0.9% |

|

All severe maltreatment |

5.0% |

13.4% |

14.5% |

More recently, a large national survey of adults resident in Wales (n=2,028) investigated the self-reported prevalence of a range of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) 51 (verbal abuse; parental separation; physical abuse; sexual abuse; domestic violence in the household; parental alcohol and drug abuse, mental illness and incarceration).

Respondents provided anonymous information on their exposure to ACEs before the age of 18 years and their health and lifestyles as adults. Table 2 summarises the findings from this study. 52

Table 2: Proportion of adults in Wales who reported having been exposed to ACEs

|

Type of ACE |

Prevalence (%) |

|

Child Maltreatment |

|

|

Verbal abuse |

23 |

|

Physical abuse |

17 |

|

Sexual abuse |

10 |

|

Child household included: |

|

|

Parental separation |

20 |

|

Domestic violence |

16 |

|

Mental illness |

14 |

|

Alcohol abuse |

14 |

|

Drug use |

5 |

|

Incarceration |

6 |

The report notes that for every 100 adults in Wales, 47 have suffered at least one ACE during their childhood and 14 have suffered four or more. However, it is important to note that not all ACEs are associated with child maltreatment.

Statistics provided by local authorities via the children in need census (and aggregated by the Department for Education in annual returns) provide data on children referred to and assessed by children's social care services. These show that in the year ending 31 March 2016, 172,290 children and young people in England became the subjects of section 47 enquiries 53, an increase of 7.6 per cent over the previous year. Around 30 per cent of these children (50,310) became the subjects of child protection plans. 54 The most common ‘initial category of abuse’ for children who were in need and who became the subject of a child protection plan is neglect, as illustrated in Table 3 below. 54

Table 3: Initial category of abuse recorded

|

Initial category of abuse |

Per cent |

|

Neglect |

46 |

|

Emotional abuse |

35.3 |

|

Physical abuse |

8.3 |

|

Sexual abuse |

4.7 |

|

Multiple |

5.5 |

Both government statistics and findings from the NSPCC study identify neglect as the most prevalent form of maltreatment. Because of its prevalence, and in recognition that conflating abuse and neglect can be problematic in terms of defining an effective response, neglect is considered in further detail below.

2.5 Neglect

Neglect is a serious and pervasive form of maltreatment that occurs across childhood and adolescence with potential long-term consequences across the life span. Babies and young children are particularly vulnerable and dependent, which makes them especially fragile and places them at higher risk of abuse and neglect and adolescents have also been highlighted as particularly vulnerable. 55 Neglect has also been found to be the most likely form of maltreatment to recur. 56 There are different types of neglect (see Appendix and these can occur together and/or with other forms of maltreatment (e.g. emotional, physical and/or sexual abuse). 57

Identifying neglect and determining whether statutory thresholds for action have been reached can present real challenges. 58 The following characteristics of neglect may make it harder for professionals to recognise that a threshold for action has been reached:

- The chronic nature of this form of maltreatment (as set out in the statutory definition) 59 can mean that professionals become habituated to how a child is presenting and fail to question a lack of progress.

- Unlike physical abuse, for example, the experience of neglect rarely produces a crisis that demands immediate, proactive and authoritative action, making it difficult to evidence that the threshold is met at a specific point in time.

- Neglect can in some cases be challenging to identify because of the need to look beyond individual parenting episodes and consider the persistence, frequency or pervasiveness of parenting behaviours, which may make them harmful and abusive.

- Practitioners may be reluctant or lack confidence to make judgements about patterns of parental behaviour, particularly when these are deemed to be culturally embedded or associated with social disadvantages such as poverty or when the parent is a victim in their own right.

- The child may not experience neglect in isolation, but alongside other forms of abuse. 60

A recent evidence review reports a number of social and environmental factors that are associated with neglect. 61 These include:

- Poverty: Child neglect is more often associated with poverty than other forms of child abuse (although it must again be noted that the majority of poor families do not neglect their children). Poverty can lead to social isolation, feelings of stigma, and high levels of stress. Pervasive stress can make it difficult for parents to cope with the psychological, physical and material demands of parenting.

- Poor living conditions: Neglect is often associated with having poor living conditions. Poor living conditions include: an unsafe home (e.g. cluttered home, holes in the floor, broken windows, exposed wires, leaky roof, infestation of rodents/insects, fixtures and appliances that are broken or not working); overcrowding; and instability (e.g. frequent moves, homelessness, short stays with friends/family, stays in shelters). It is important to bear in mind, however, that neglect also occurs in households with good living conditions but where parents are physically and emotionally unresponsive.

- Social isolation: Parents who neglect their children have, or perceive themselves to have, fewer individuals in their social networks and to receive less support than other parents. This may exacerbate other parental vulnerabilities (see section 2.2).

- Men: Most of the evidence around neglect relates to mothers rather than fathers. Men can be a source of risk and a source of protection to children they are raising. 62 Fathers can be overlooked in assessment in child protection. 63

Some characteristics of young children are also associated with elevated risk of neglect. This is especially the case for babies born before term, with low birth weight, or with complex health needs and disabilities.

2.6 Risk of maltreatment for children with disabilities

There is a growing body of evidence on the increased risk of maltreatment for children with disabilities. #dummy requires link A recent evidence review, based primarily on research from the United States, suggested that there is an association between child disability and all forms of maltreatment. Children with particular impairments, including communication difficulties, sensory impairments, learning disabilities and behavioural disorders, appear to be at heightened risk. The review also found that children with disabilities may experience multiple kinds and episodes of abuse. 65 Although there is an association between disability and child maltreatment, it is not clear whether the maltreatment a child has suffered contributes to their disability or whether their disability puts them at higher risk of maltreatment. 66

The proportion of children in England who are disabled is a contested issue, partly because of differing definitions and sources of data. 67 Children who are disabled do not form a homogenous group, either in severity or type of disability nor in their life experiences. So an understanding of the nature of any disability and how a child’s development is affected are essential in order to appreciate the nature and impact of any maltreatment a child may be experiencing. 68

Disability was a feature in 12 per cent (21 of 178) of cases in the triennial analysis of serious case reviews 2011-14. Cases in the 2011-14 review (and previous reviews) have highlighted the risk of harm going unrecognised, with families sometimes presenting as loving and cooperative. For children of all ages, there was a tendency to see the disability more clearly than the child, with some professionals accepting a different and lower standard of parenting for a child with a disability than would be tolerated for a non- disabled child (e.g. keeping a child shut in the bedroom for 'safety'). 69

A number of reasons for the increased risk of maltreatment for children with disabilities have been proposed, including:

- Individual and societal attitudes and assumptions that are discriminatory and stigmatising. These include a reluctance to believe children with disabilities are abused, and minimising the impact of abuse.

- Professionals not recognising the signs of abuse or neglect. Behaviours indicative of abuse (e.g. self-mutilation and repetitive behaviours) may be misconstrued as part of a child’s impairment or health condition.

- The children's dependence on a wide network of carers and other adults to meet their medical and intimate care needs, which create increased opportunities for maltreatment.

- Communication barriers, which mean that children with disabilities may have difficulty reporting worries, concerns or abuse. Professionals may also fail to consult them and to listen to their experiences.

Professionals' reluctance to challenge carers, together with a sense of empathy with parents/carers who are under considerable stress. 70

Parents of children with disabilities may also experience difficulties (e.g. depression) and isolation as a result of caring for their child. This is sometimes compounded by the lack of consideration given to the impact of the child's disability on family functioning and economic status (e.g. as a result of having to give up work to care for a child), as well as lack of support from statutory services. 71

3. The impact of maltreatment on children and young people

Key points

- Abuse and neglect can have a negative impact on a range of outcomes for children and young people. However, every child is unique and has his or her own susceptibilities and resiliencies. The impacts of exposure to maltreatment vary in relation to factors such as the age at which it is experienced; the intensity, frequency, duration and type of maltreatment; and the individual characteristics of the child.

- It is not possible to predict specific outcomes for individual children based solely on research findings. However, some findings are consistent across research studies. This indicates they should be taken into consideration when making decisions about children's welfare in the immediate term and into the future, alongside critical and analytical observations and assessments of individual children and their circumstances.

- There is strong evidence to suggest that maltreatment is associated with social, emotional, behavioural and mental health difficulties, which can continue throughout childhood and beyond. Although this can have an impact on educational achievement for some children, being at school can also act as a buffer against the negative consequences of maltreatment.

- The mechanisms for these negative outcomes are not fully understood, but may be linked in part to the development of disorganised attachment behaviours in infancy and/or in part to the body's physiological response to the maltreating environment.

- Positive changes to the caregiving environment – specifically, the provision of nurturing, stable and consistent care – can help children recover from the negative consequences of maltreatment.

- Support for carers is crucial both to help them understand the impact of maltreatment on the child's behaviour and so to assist with the child’s recovery. Children and young people may also need specialist support to help them recover from early trauma.

3.1 Introduction

Although research investigating the impact of child abuse and neglect is extensive in some areas, it is difficult to make direct causal links between specific types of experience of abuse and neglect and specific adverse outcomes for children. Many research studies do not control for other adverse environmental and social factors such as socio-economic disadvantage, disability and social isolation. Other research limitations include: problems with definitions of the type and severity of maltreatment (e.g. physical abuse, emotional abuse, neglect); difficulties in recruiting representative samples; and difficulty obtaining accurate recollections of past events by participants. 72

Neglect and abuse occur along spectrums of severity and the evidence suggests that the more chronic the experience, the more marked the symptoms of trauma in childhood and beyond. Impacts may be moderated by various factors including: the child’s age when neglect or abuse commences or occurs; the duration of the maltreatment; availability of protective factors such as sources of nurture and support; individual characteristics in a child’s temperament and genetic characteristics. 73

As previously noted, children have differing susceptibilities and resiliencies to maltreatment; it is not possible to make definitive predictions about the impact of abuse and neglect on children at an individual level. The outcomes for children who are maltreated are determined by multiple factors and 'similar end points can arise from quite different mechanisms and conversely, similar experiences can lead to quite different outcomes '.74 The exception to this is where children suffer severe physical abuse resulting in brain injury or even death (e.g. shaken babies).

Notwithstanding the limitations, research consistently identifies strong links between maltreatment and adverse consequences for children and young people. Local authorities, Cafcass and the judiciary can utilise these findings to inform their assessments and decisions, alongside their professional judgement and expertise.

3.2 The impact of neglect

The impacts of neglect, as with other forms of maltreatment, will vary between individual children. It is with this understanding that the evidence regarding impact should be considered.

Evidence suggests that neglect is a particularly damaging form of maltreatment. Although it can be difficult to disentangle specific effects from those of other forms of maltreatment, there is evidence that for many children neglect has significant implications for a range of developmental dimensions, including health, education, identity, emotional and behavioural development, family and social relationships, social presentation and self- care skills. 75

Neglected infants and toddlers can show a dramatic decline in overall developmental scores between the ages of 9 and 24 months and a progressive decline in cognitive functioning in the pre-school years. In addition, neglected infants who initially display secure attachment behaviours may increasingly develop insecure or disorganised attachment behaviours as they grow older. These findings suggest that the longer young children are exposed to neglect, the greater will be the harm. 76

The experience of neglect in childhood can have long-term impacts on child and adolescent development. For instance, children who have experienced neglect may experience increased vulnerability in adolescence compared to those who have been physically abused 77, potentially increasing the vulnerability of some young people to other types of maltreatment and/or victimisation, such as sexual exploitation (though this is an area requiring further research). 78

In some cases, extreme neglect can be potentially life threatening. The analysis of serious case reviews in England 2011-14 found that neglect was an underlying feature in 62 per cent of the children who suffered non-fatal harm, and in over 50 per cent of the children who died (it should be noted this number is small in relation to the total population of children). Six children aged between four months and just over seven years died over this period directly as a result of extreme neglect (three per cent of all fatal serious case reviews). These children died either as a result of cardiac arrest or multi- organ failure arising from malnutrition. All six were known to children's social care and two were on child protection plans. In all six cases, there was evidence that the family was isolated or that the mother was particularly vulnerable. 79

3.3 Attachment theory and the impact of maltreatment on attachment

Attachment theory

An area where there is relatively broad consensus in the research literature is the adverse impact of child abuse and neglect on the formation of infant attachments. Attachment theory 80 has developed over a number of decades and focuses on the foundational importance of secure and lasting relationships with a caregiver for infant and child development. It should be noted that, whilst attachment theory is widely drawn upon in work with children and families, it is also subject to some critique particularly in relation to methodological issues and causality, and therefore continues to evolve. 81

Security of attachment refers to the degree to which a child has internalised experiences based on relationships with significant others who are perceived as trustworthy, available, sensitive and loving. Early attachment is important because it enables children to learn to trust, develop empathy for others and feel secure knowing that their primary caregiver/s will meet their needs. It is also believed to act as an ‘internal working model’ (or template) for subsequent relationships. 82 Attachment security is also important in adolescence and exerts a similar effect on development as it does in early childhood: a secure base fosters exploration, independence and the development of cognitive, social and emotional competence. 83 Parents’ own attachment patterns (developed, attachment theory suggests, through their experiences of early childhood) also influence parenting capacity, but do not define it. 84

Attachment theory identifies a number of ‘attachment patterns’ which develop through early parent-child interaction, whatever the quality of that interaction, and including in the context of maltreatment. Appropriate and sensitive parental attunement and responsiveness give rise to secure attachment. A consistent and emotionally available caregiver comforts the child and provides a secure base when the child is anxious or distressed. Secure and insecure (i.e. avoidant or ambivalent) attachment are termed ‘organised’ attachment patterns; each is a consistent and predictable way for children to keep carer(s) nearby. Insecure attachment is very common, with an estimated 60/40 split between ‘security’ and ‘insecurity’ amongst the general population. Although it is not optimal, and children may benefit from support and more sensitive parenting, insecure attachment is not in itself cause for alarm. 85

Children who have a secure attachment are generally able to turn to and be comforted by their caregivers when distressed and to use them as a 'secure base' for exploring their environment. Children who have an ambivalent attachment pattern tend to 'up-regulate' their attachment behaviour to maintain proximity to their carer, becoming very distressed when separated and not easily being calmed when comfort is offered. In contrast, children who develop an avoidant attachment pattern tend to maintain proximity by 'down-regulating' their attachment behaviour, appearing to manage their own distress and not signalling a need for comfort.

It is important to note that categorising attachment behaviours is complex and is not an exact science. For example, while insecure attachment behaviours may be observed when the child is exposed to a stressful situation (e.g. separation-reunion procedure), they may not display these behaviours all the time. 86

Disorganised attachment behaviours are described in the literature as being a set of fleeting, temporary behaviours, usually only observable when the ‘attachment system’ is activated (e.g. when the child’s sense of safety/security is threatened, such as when they are hurt, unwell or emotionally upset and/or frightened 87). Examples of this behaviour include infants approaching their caregiver but with the head averted, with fearful expressions, or disoriented behaviours such as dazed or trance-like expressions or freezing of all movement. Such behaviours are understood to mean that the infant is not able to resolve their distress within the context of their relationship, either by signalling their anxiety to their caregiver, or by directing their attention away from them. While it cannot be assumed that their presence always indicates maltreatment, research studies have suggested that these behaviours may be observed in between 48 and 80 per cent of maltreated children. Some children (e.g. those on the autistic spectrum, or children who are frightened for their carer, for example when a parent is terminally ill or subjected to violence) can exhibit disorganised attachment behaviours in the absence of maltreatment. Conversely, it is possible for children who are maltreated not to show disorganised attachment behaviours. 88

The attachment behaviours described above are different to an attachment disorder, which is a formal psychiatric diagnosis outlined in DSM-5. 89 The term 'attachment disorder' is prone to overuse or misuse by practitioners without appropriate psychiatric qualifications to diagnose. 90

Attachment disorder refers to a highly atypical constellation of behaviours indicative of children finding it extremely difficult to form close attachments. Reactive attachment disorder refers to a consistent and pervasive pattern of extremely withdrawn behaviour, with a marked tendency to not show attachment behaviour toward others, accompanied by a general lack of responsiveness and limited positive affect. Disinhibited social engagement disorder refers to a marked and pervasive tendency to not show appropriate cautiousness with respect to unfamiliar adults and a failure to be sensitive to social boundaries. 91

The criteria for formal psychiatric diagnosis of an attachment disorder is that the child has experienced a pattern of extremes of insufficient care in at least one of the following:

- Social neglect or deprivation in the form of persistent lack of having basic emotional needs for comfort, stimulation, and affection met by caring adults

- Repeated changes of primary caregivers that limit opportunities to form stable attachments (e.g. frequent changes in foster care)

- Rearing in unusual settings that severely limit opportunities to form selective attachments (e.g. institutions with high child to caregiver ratios). 92

The impact of maltreatment on attachment

Attachment behaviours are thought to be adaptations to the quality of the caregiving environment. Although they make sense as a way of coping with impaired caregiving, they may have consequences for later well-being. 93 There is some evidence (though not uncontested) that children who are abused and/or neglected may be at risk of developing attachment patterns or behaviours that can increase the risk of later psychopathology; externalising disorders (e.g. conduct and behavioural problems); and personality disorder. 94 However, variations in infant–caregiver attachment cannot explain all the negative outcomes as parents are not the only important social influences on children's development. Sibling and peer relationships are also important and combine with other parenting behaviour to influence development and future outcomes. 95 Some research notes that application of attachment theory to developmental psychopathology, highlights conceptual and methodological challenges 96; this underlines the importance of not assuming attachment difficulties in childhood will translate to later problems.

Although attachments patterns show some stability over time, they are also open to change as a consequence of changes in caregiving. However, because children with attachment difficulties related to maltreatment are often not used to adults being predictable, kind and nurturing, they may inadvertently reject their carers (e.g. kinship carers, foster carers, adopters, special guardians). The behaviours associated with such attachment difficulties can be experienced as very demanding by carers seeking to offer a secure base and safe home. Thus, carers may need additional input to help them understand the behaviours and to support them in maintaining the placement. 97

3.4 Impact of maltreatment on physiological functioning

Research on the impact of maltreatment on the body's physiological responses and on neurodevelopment is not yet at a stage where definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding the interrelated biological, psychological and social factors involved. It is not possible to predict specific outcomes for children based on their experiences of maltreatment. Some research indicates that some children who have been maltreated will have 'complex and individualised neurodevelopmental problems, which could influence their emotional and behavioural adaptations in a variety of ways'. 98 However, researchers also warn that the generalisability of most of these findings is limited as they are disproportionately reliant on clinical samples, which are not representative of all children. 99 Further research is needed before these findings can be applied with confidence in practice.

Research suggests that maltreatment may have an impact on the body's systemic response to stress. A certain amount of stress is normal for all children in their daily lives; and they have inbuilt systems for identifying and responding to physiological, emotional and social stress, which are also developed through experience. However, some research argues that acute stress experienced over a short period of time can have long- term consequences (e.g. post-traumatic stress disorder), and that chronic stress can have short- and long-term consequences. The various systems in the body adapt to the experience of stress and this may have varying degrees of impact on child, adolescent and adult development (e.g. increase the risk for chronic diseases of ageing, including Type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease). 100 However, care must be taken not to assume that maltreatment will result in these impacts. Care must also be taken not to overlook the impacts of other contextual factors.

Evidence emerging from the use of relatively new techniques such as neuroimaging is limited and evolving, and its application to policy and practice is contested. These techniques have been used, for instance, in studies that suggest a pattern of atypical processing of threat-related cues in children who had been exposed to family violence compared to children who had not experienced family violence. 101

Although physiological dysregulation can have consequences for an individual’s development and well-being, there is increasing evidence to suggest that a change to a high-quality nurturing environment (either through positive parental changes or, where improvements cannot be sustained, through placement with alternative carers) can help to stabilise physiological dysregulation. 102 These findings again emphasise the importance of not adopting a deterministic perspective.

3.5 The impact of maltreatment on social, emotional and behavioural development

Much of the UK evidence on the impact of maltreatment on children and young people’s social, emotional and behavioural development derives from research with looked after or formerly looked after children. Since the majority of children become looked after following abuse or neglect (60 per cent in England in 2015-16) these studies provide proxy measures of the impact of maltreatment. 103

Evidence from a number of UK research studies indicates that many children who become looked after (and are at high risk of having been maltreated) have high levels of emotional and behavioural difficulties, which are associated with poor mental health and educational progress. 104 One of the main measures used to assess children's emotional and behavioural well-being is the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) 105, a reliable and well-validated screening instrument that can be completed by older children, parents/carers and teachers. There is a strong predictive relationship between SDQ total scores that are in the clinical range and subsequent psychiatric disorders. 106

Biehal and colleagues' longitudinal study of outcomes for children in long-term foster care and adoption found that over a third of children (38 per cent; n=136) had scores over the clinical threshold for severe emotional and behavioural difficulties, as measured by the SDQ, almost four times higher than would be expected in the general population. Scores were especially high on the scales for hyperactivity, peer problems and conduct disorder (33, 36 and 38 per cent respectively). Boys scored more highly than girls for hyperactivity, but children with learning disabilities scored highly across all sub-scales. 107

One of the limitations of this study is that it was unable to measure children's emotional and behavioural difficulties prior to them entering care. Sempik and colleagues sought to overcome this problem by examining the needs of children (n=648) who had not previously been looked after at the point of entry into care to explore emotional and behavioural problems recorded by social workers and psychologists. Using the threshold of 'problems being of concern to current or previous carers', they found that 72 per cent of children aged 5 to 15 showed indications of behavioural or emotional problems at entry to care, with half showing indications of conduct problems and 22 per cent showing only emotional problems. Almost a quarter of children aged under five at entry to care were identified as having indications of emotional or behavioural difficulties. 108

It is not just the severity of maltreatment that influences emotional well-being, but also the length of time spent in an adverse environment and the number of moves in care. 109 For example, research from the US, looking at 729 children, suggests that placement stability in foster care, independent of children's problems at entry into care, can influence their emotional and behavioural well-being. Children who did not experience placement stability were estimated to have a 36 per cent to 63 per cent increased risk of behavioural problems compared with children who had a stable foster placement, regardless of the child's baseline risk for instability (see section 4.6 for further discussion on placement stability). 110

Given the evidence, every effort should be made, firstly to support parents to achieve positive change, and, where this is not possible, to place children in an alternative, nurturing and stable environment at the earliest opportunity.

3.6 The impact of maltreatment on mental health

There is evidence of a significant association between maltreatment and poor mental health in childhood and later life. 111 A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature on the long-term health consequences for children exposed to abuse and neglect found evidence to suggest a causal relationship between child maltreatment and a range of mental health issues and other problems including:

- depressive disorders

- anxiety disorders

- eating disorders

- behavioural and conduct disorders

- drug use

- vulnerability to sexual exploitation. 112

A large scale survey (n=2,500) by Meltzer and colleagues between 2001 and 2003 collected data on the mental health of children and young people looked after by local authorities in England (not including those with short-term placements) and compared this with data collected on non-looked after children. The study used both structured and open-ended interviews with parents/carers, young people and teachers. The prevalence of mental disorders was based on a clinical evaluation of the data collected by interviewers using questionnaires designed by the Institute of Psychiatry in London. 113 The findings are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4: Comparison of looked after children with non-looked after children for emotional and behavioural disorders 114

|

|

5-10 year olds |

|

11-17 year olds |

|

|

|

Looked after children |

Non looked after children |

Looked after children |

Non looked after children |

|

Emotional disorders |

11% |

3% |

12% |

6% |

|

Conduct disorders |

36% |

5% |

40% |

6% |

|

Hyperkinetic disorders |

11% |

2% |

7% |

1% |

|

Any childhood mental disorder |

42% |

8% |

49% |

11% |

Conduct disorders contributed to the largest difference in psychopathology between looked after children and non-looked after children. The prevalence of mental disorder was greater among boys than girls (49 per cent and 39 per cent respectively). The study noted that prevalence of mental disorders decreased with the length of time in placement, indicating the mediating effect of moving to a nurturing and stable environment.

These findings are consistent with those from a study comparing psychiatric disorder among looked after children in Britain with disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged children living at home. 115 The study found that looked after children showed elevated rates of emotional and behavioural problems when compared to children who were living in birth families where there was significant social disadvantage (Table 5). The conclusion drawn is that the experience of maltreatment prior to entering care is a key factor in subsequent mental disorders.

Table 5: Comparison of rates of mental disorder among British children aged 5-17 116

|

Category of disorder |

Non- disadvantaged children |

Disadvantaged children |

Looked after children |

|

Any disorder |

8.5% |

14.6% |

46.4% |

|

Anxiety disorders |

3.6% |

5.5% |

11.1% |

|

Post-traumatic stress disorder |

0.1% |

0.5% |

1.9% |

|

Depression |

0.9% |

1.2% |

3.4% |

|

Behavioural disorders |

4.3% |

9.7% |

38.9% |

|

ADHD |

1.1% |

1.3% |

8.7% |

|

Autistic spectrum disorder |

0.3% |

0.1% |

2.6% |

|

Other neurodevelopmental disorders |

3.3% |

4.5% |

12.8% |

|

Learning disability |

1.3% |

1.5% |

10.7% |

It should be noted that these findings are based on data from around 15 years ago. More recent data of this kind is not available, although evidence suggests that the prevalence rates for some mental disorders (e.g. depression and conduct disorders) among young people are increasing. 117

3.7 The impact of maltreatment on educational achievement

Social interaction with caregivers and others is crucial to the communicative competence of young children, even at the pre-verbal stage of development. Maternal warmth, acceptance and responsiveness have been found to be positively correlated with the development of communication skills. In contrast, research indicates children with early experiences of abuse and/or neglect are at increased risk of delayed or impaired language and communication skills development, which can then have an impact on their social and educational development. 118

The relationship between maltreatment and an increased risk of emotional and behavioural problems is indicative of children being at greater risk of behavioural difficulties in the classroom, which is likely to have an impact on educational achievement. 119 This is supported by research which shows that children with more severe emotional and behavioural difficulties, as measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), were generally doing worse at school than those with fewer problems. The correlation between SDQ scores and poor educational progress was strongest for those with high scores on the SDQ hyperactivity scale. 120

It is important to note that comparing the academic achievement of a group of maltreated children with results for the general population does not control for other factors (e.g. poverty and deprivation) known to influence educational attainment. However a review of the international evidence supports the notion of a link between maltreatment and academic performance. 121 This evidence review suggests that maltreated children are:

- at greater risk of poor school behaviour

- at greater risk of being the victims of bullying in school

- more likely to have special educational needs

- at greater risk of exclusion from school

- more likely to be absent from school. 122

Evidence from a study that used data from the National Pupil Database (NPD) and the data on Children Looked After in England (SSDA903) found that educational progress was dependent on a number of factors, including age at entry to care and the length of time in care. Detailed findings from this study can be found in section 5.5. 123

There is also evidence to suggest that parental vulnerabilities such as substance misuse and domestic violence can negatively affect children's cognitive development and educational achievement. This is thought to be a consequence of:

- the parents' problems dominating the child's thoughts and affecting his or her ability to concentrate at school

- difficulties in attending school regularly because they need to take care of themselves, their parents or siblings

- disruption to schooling because of families having unplanned moves. 124

However, research also shows that children whose parents have these problems do not always have problems at school, and that school can offer respite and a safe haven from troubled home circumstances. 125

3.8 Impact of maltreatment in utero

Many children who enter care have been exposed to maladaptive environments prenatally (e.g. through drug and alcohol abuse). The adverse impact of alcohol misuse during pregnancy is widely accepted and can result in irreversible neurological and physical abnormalities. 126 Excessive alcohol use during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage and can cause Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). Symptoms of FASD include:

- stunted growth

- distinct pattern of facial features and physical characteristics (if alcohol is abused during the first trimester when the facial features are formed)

- central nervous system dysfunction. 127

However, there are challenges in examining the impact of drug misuse on foetal development and the longer-term impact on children’s development because mothers often use multiple substances and may also have a poor diet and limited access to antenatal care, which can also affect foetal development.

The effect of substance misuse on the developing foetus is thought to be dependent on three interrelated factors:

- the pharmacological composition of the drug

- the gestation of pregnancy

- the route, amount and duration of drug use. 128

Exposure to domestic violence can also adversely affect the unborn child as a result of physical damage to the foetus through punches or kicks to the abdomen 129 and also, it is suggested, through the impact of maternal stress on the developing foetus. 130 While domestic violence can start in pregnancy for some women, it is more likely to occur where there has been violence pre-pregnancy. Although pregnancy is potentially a time of increased vulnerability for some women, it can also offer protection for others as they may be more likely to be motivated to seek and engage with support at that time. 131

3.9 The impact of maltreatment experienced during adolescence

Adolescence is a concentrated period of physical, hormonal, social and emotional change. It is also a time of increasing independence, exploration and establishing boundaries. This is part of normal adolescent development. For some young people, however, it can be a time of heightened vulnerability and exposure to maltreatment. Adolescents who are navigating the transition to adulthood without a supportive home environment, and young people with early experiences of abuse and neglect, are at increased risk of experiencing more complex and challenging problems at this developmental stage. 132 Adolescents are more likely than younger children to suffer abuse outside of the family. They may become ensnared in behaviours that exacerbate their risk of harm (e.g. substance misuse, going missing from home or school) and they may be incorrectly assumed to be making unconstrained ‘choices’, which means their vulnerability can sometimes be overlooked. 133

Parenting that is neglectful or abusive (at any stage in a child's development) is associated with a range of negative outcomes for young people in the longer term, including: poor mental health and well-being; behaviours that present heightened risk to health (e.g. drug and alcohol misuse); poor academic achievement; antisocial behaviour; offending; and suicide or self-harm. Once again it is vital to note that these associations cannot be taken to indicate causal links between neglectful parenting and negative outcomes. There is also some evidence of reciprocal links; for example, young people’s involvement in offending may put a strain on their relationships with parents and cause parents to disengage. 134 As noted in previous sections, these harms and vulnerabilities tend to interact in complex ways, with some young people experiencing a range of harms that compound each other and can be further compounded by ineffective service responses. 135

There is relatively little research on the maltreatment of adolescents and its consequences, although the work of Stein and colleagues provides working definitions and analysis on neglected adolescents. 136 There is a small amount of research that has explored the relative outcomes for children and young people who are maltreated at different ages. These studies suggest there may be distinctive outcomes according to the age at which maltreatment occurs, with an increased risk of earlier experiences of maltreatment leading to internalising problems at a later stage, and later experiences of maltreatment potentially leading to a wider range of negative outcomes, including behaviour towards others. 137

The triennial analysis of serious case reviews for 2011-14 found that neglect featured prominently in the experience of adolescents at the centre of serious case reviews. Analysis of these reviews suggested that the impact of maltreatment (both abuse and neglect) over time on these young people was not acknowledged by some of the professionals working with them. In some cases, the young person was wrongly seen as being resilient because they were articulate and troublesome. 138 This tendency for young people to be seen as ‘streetwise’, resilient and troublesome (rather than troubled), and for their behaviours to obscure their vulnerabilities and strengths, has also been noted by others. 139

3.10 Evidence-based interventions and support for children who have been maltreated

A number of evidence-based programmes have been reported as being effective in improving outcomes for children and young people who have been maltreated (e.g. Multi- Systemic Therapy; Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care; Functional Family Therapy; KEEP – Keeping Foster and Kinship Parents Trained and Supported), although some do not always transfer effectively into the UK context. 140 It is beyond the scope of this report to review the effectiveness of these interventions or the associated barriers and enablers to effective implementation, but at the core of all these programmes is an approach based on working intensively with the child or young person together with their birth or carer family. The programmes share a number of other features including: engagement with the child and parents/carers; developing positive family relationships; promoting pro- social peer relationships; improving parenting skills; and providing clear and consistent behavioural boundaries.

A recent evidence review on the efficacy of 15 of the most well-used and high-profile therapeutic post-adoption support interventions concluded that there were very few robust published studies currently available to provide evidence of the effectiveness of the interventions (including play therapies, therapeutic parenting training, conduct problem therapies, cognitive and behavioural interventions). 141

4. Placements options for children

Key points

- Children and young people enter care for a variety of reasons. The 'right' placement for individual children will depend on a variety of factors. Decision makers need to undertake thorough and analytical assessments to help them weigh up the pros and cons of the different permanence options and to determine which placement will best meet children's needs through the whole of their childhood and beyond.

- Where children and young people are not able to remain safely with their parents, decisions around securing stable long-term placement should be made at the earliest opportunity as lengthy waits in temporary care and placement moves can have negative consequences for children.

- Placement stability is a key element of permanence. There are a number of interrelated factors that have an impact on stability, including: the age of the child when they enter care; the severity of social, emotional and behavioural difficulties; having a carer who is sensitive, tolerant and resilient; having a carer who can promote the child's sense of identity.

- Siblings are an important part of a child's identity. There are generally clear advantages to placing siblings together, but this is sometimes not achievable and sometimes not desirable. Decision makers need to consider the benefits and detriments of sibling placements for individual children, and, if children need to be separated, have a plan for contact wherever it is safe to do so.

- The benefits and detriments of contact with birth relatives will depend on a variety of factors related to both the child and the relatives. Of particular importance is the quality of contact and the benefits for the child or young person. Crucial to any decision regarding contact is the child's welfare and their expressed views and experiences of contact.

4.1 The legal context for care proceedings

Section 31 of the Children Act 1989 sets out the legal basis (the threshold criteria) for the court to make an emergency protection order 142, care order, or supervision order. A court 'may only make a care order or supervision order if it is satisfied:

- that the child concerned is suffering, or is likely to suffer, significant harm; and

- that the harm, or likelihood of harm, is attributable to —

- the care given to the child, or likely to be given to him if the order were not made, not being what it would be reasonable to expect a parent to give to him; or

- the child’s being beyond parental control' (s.31(2)).

When a court considers any question relating to the upbringing of the child it will consider:

- 'the ascertainable wishes and feelings of the child concerned (considered in the light of his age and understanding)