Reframing social work - Expectation, reality and change

Published:

This resource from Richard Devine outlines how a different perspective on the role of social worker might liberate practitioners to better support the people they are working with. Each section looks at a different part of social work and explores how we can make effective changes to practice.

Introduction

Social workers hold powerful positions when working with children, young people and families. Whilst it is a very fulfilling profession, the role comes with a heavy burden of expectation that we are agents of change. The weight of this perception can pressure social workers to pursue ‘perfect’ outcomes which unfortunately hinder realistic possibilities.

In this resource, Richard Devine outlines how a different perspective on the role might liberate practitioners to better support the people they are working with. Each section below looks at a different part of social work and explores how we can make effective changes to practice.

Contents

Select the quick links below to navigate through the resource.

Reducing harm Power imbalance Time as a resource Role of social workers Making a difference

Making parents change A bridge for change Ethical social work Personal values

Reducing harm is the goal, not eradicating it. This does however ask us to question how we work with families to achieve our aims and balance the power.

An important lesson is to realise the role of social worker is to reduce the concerns held for the children so they are not exposed to significant harm. However, in my opinion, an important distinction is that it is not the role of a social worker to make children safe. We do have safeguarding responsibilities, but it’s about empowering the parents and network.

Is it a misconception that we can facilitate change through our relationship with parents? It is presupposed that through ‘relationship-based practice’ we are trained and capable of having conversations and delivering interventions that facilitate change. Undoubtedly this is desirable and perhaps a primary motivation for social workers entering the profession, yet, it may often remain an unattainable ambition.

Considering power imbalance

Social workers are representatives of statutory organisations. Unfortunately, this often means many parents feel an imbalance of power which can lead to negative connotations. If the job is to help a family in need who wanted it, that would be pretty straightforward. However, it is actually to decide whether a parent needs support and whether it is necessary to impose that support against their will to safeguard their child.

In social work you often make the decision to curtail a parent’s freedom and liberty, and the role is often about managing the complex dynamics produced as a result.

Here are some example situations to consider:

- Visiting a nine-year-old child subject to a child protection plan, his mum says he does not want you to see him and that he is scared of meeting new people.

- Speaking to a mum about the impact that her suspected drug use is having on her unborn baby, she adamantly denies drug use.

- Writing a conference report about home conditions being unhygienic and unsafe, the dad is affronted and vehemently disagrees.

- Delivering pre-proceedings letters to parents, the mum rips the letter up on the doorstep. She screams and swears at you.

In each of these situations, the parents react to a power imbalance – and a sense of injustice.

From the perspective of parents in the examples above, they are having their right to a private family life taken away. Many parents express dissatisfaction because of what social workers represent. A statutory organisation.

They don’t want social work involved, not necessarily because of who you are, but because of what you represent. There are at least two reasons for this.

- First, there is often a disagreement about the legitimacy of the concerns identified about the child.

- Second, most parents fear that social work involvement could result in the loss of their child. It is hard to imagine many people would want to work with a system where that could be the outcome, even if it meant access to some much needed help.

Lady Hale, a retired judge, captured this in a speech she made 30 years after the inception of the Children Act 1989 - an act for which she led the creation of.

The aspiration of developing a partnership between children’s services and families with children in need proved very difficult to achieve… The trouble is that, if efforts to work with families run into difficulties, the local authority can always resort to care proceedings and the families know that.

So in order to shift this portrayal we need to build good working relationships with the families we are working with, however this can be challenging with the volume of cases.

20 minutes every fortnight adds up to 40 minutes per month, which amounts to 8 hours per year. 8 hours out of a total of 8760 hours in a year. In percentage terms, 0.1%. In other words, 99.9% of the time, a parent is influenced by other relationships, life circumstances and factors.

It is hard to build therapeutic relationships in limited time. In many cases, even when children are subject to a child protection plan, social workers visit parents once a fortnight at most

While there might be telephone contact and core group meetings, the statutory Svisit provides the best opportunity for building a relationship. During a statutory visit, as social workers, we have to share any recent concerns with the parents (which some will object, minimise, or deny causing friction), check the home conditions and the bedrooms, and speak to the children.

Therefore, a social worker typically only spends limited time with a parent. This short amount is the only time we have to influence someone's thinking, way of dealing with feelings, patterns of behaviour, addiction, and relationships.

Other factors include their childhood and current relationships, such as children, parents, brothers and sisters, neighbours, and a partner.

They might have ongoing issues stemming from the past or current context, such as substance use or mental health difficulties. Or they might have financial, housing, health or employment issues. These concerns deprive the relationship of two key evidential ingredients - Psychological safety and Time.

Even if we have more time, and I wish we did, our relationship can often not be meaningfully leveraged as a vehicle for change because of the burden of responsibility we feel. When reading Working with Denied Child Abuse by Andrew Turnell and Susie Essex, I came across an idea that really helped me think about how we support children and families and the networks around them.

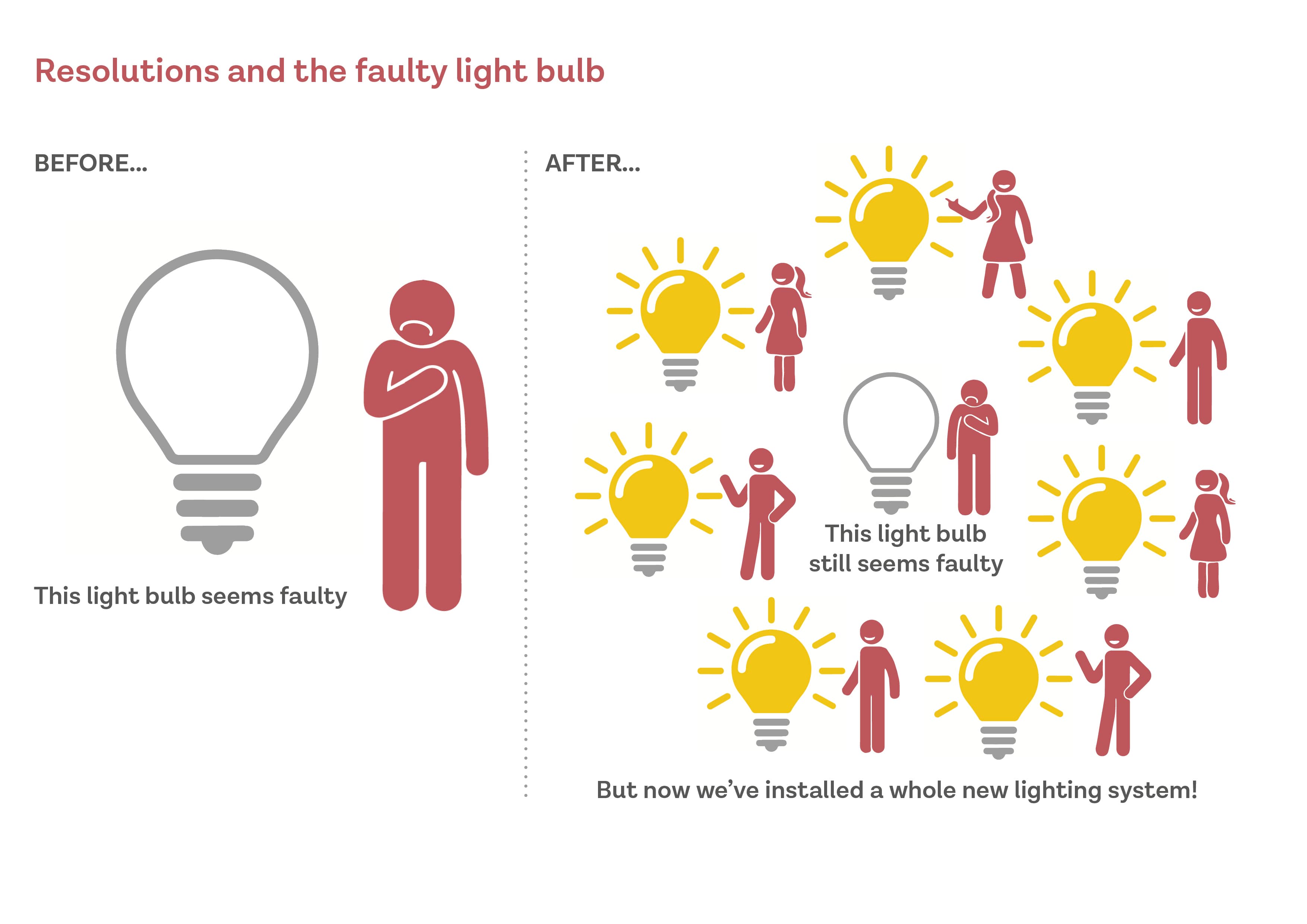

If we try to fix the broken lightbulb we seek to help a family by identifying an issue and then work to help the parent with that particular issue. For example, suppose a parent has a drug or alcohol problem. In that case, we encourage them to think about change and make a referral to the drug and alcohol service. We identify the risk, and then we encourage and support the parent to address the issue that has been construed as problematic. The second way, as we have just been exploring, is to identify support with the family system or through professional interventions that could ameliorate the impact of the issue on the child.

I think an effective intervention is anything that improves the quality and quantity of relationships in a child’s life but how do we encourage change?

Although social workers utilise learning from counsellors and therapists we are not in those fields.

One idea we have used, perhaps uncritically, is that social workers can be therapeutic agents of change. When we fail to establish a therapeutic relationship - which we inevitably do - we become demoralised and either:

- Blame ourselves; or

- Blame the system for not providing a context to build the type of relationships we were told would be possible.

We have an important task in clarifying where and how we can navigate relationships so all parents who come into contact with social workers are treated with dignity, respect and in a way that maximises the chance of bringing about change.

If we can achieve this, it might remove the unnecessary burden of responsibility that social workers feel. Instead of focusing on relationship-based social work, maybe we should aspire for a principled and ethical, rights-based social work.

However, that is potentially a less romantic and less inspiring framing of social work, but it might at least bridge the gap between expectations and reality – and avoid social workers feeling disillusioned when we realise we don’t have time to do the work we imagined.

But also, child protection social work as a form of rights-based, case co-ordination – in contrast to unattainable, idealised notions of relationship-based practice - should be celebrated as a noble, worthwhile, and fundamentally important role that improves the lives of children and families.

We do have a meaningful impact.

An example we could look at is one from my own life experience. At age 11 a social worker came to our house. I was guided into the living room, where we sat opposite a middle-aged woman with white curly hair, leaning forward with her arms crossed over a notepad covering her knees. She asked several questions about my life, and then I was allowed to leave.

At the time, I had no idea why she visited or what the purpose was. I never saw her again. Looking back, however, I suspect the social worker undertook an initial assessment due to my dad being in rehab for his drug and alcohol use and my mum suffering from depression and chronic fatigue syndrome.

A few weeks later, I began attending an organisation called Young Carers. Through them, I attended weekly groups where we did fun activities and group work. By attending, I filled out many wishes and feelings sheets which I would subsequently use with children in my role.

I also went on activity days during half terms, and a few times I went on a residential trip in the summer holidays. As I got older, I was provided one-to-one counselling.

At 16, when I was too old to continue attending, I was offered a role as a volunteer, which essentially allowed me to continue accessing support while also pretending that I was helping and giving back. This voluntary position was a vital learning experience that helped me when I applied to college to undertake my BTEC National Diploma in Health and Social Care. I learned as an adult that I attended Young Carers because the social worker who had visited all those years before made a referral for me to attend.

I hope this does not sound too dramatic, but that social worker changed my life. She did not try to intervene herself, make herself responsible for building a therapeutic relationship or even try to change my parents. Instead, she identified a need and made a referral to a service that could provide long-term, quite intensive, and ultimately therapeutic support that profoundly altered my outcomes and life chances.

According to research by Donald Forrester and his colleagues, a very common way of helping parents is for a social worker to tell them what their problem is and why they need to change.

This is a very understandable approach, especially if you believe it is your job is to make people change.

Another example from my own experience is my dad. He was abandoned by his mother, removed from his father, subject to multiple placements, attended 27 different schools, and then in adulthood was a chronic and severe drug addict. I can see starkly the absurdity of expecting him to overcome his trauma, entrenched personality issues and addiction as a result of a social worker telling him he had an alcohol problem – or that he needs to prioritise his child’s needs – or that he was harming his children – even if those things are all true, it would very unlikely bring about change.

However we still, as social workers, continue to do it. For many other parents like my dad they are profoundly fearful of losing access to and giving up a behaviour that helped them cope and deal with their suffering.

It isn’t simply a case of giving up a drug or a relationship or whatever it might be.

It is giving up the only solution they have found to dealing with the unbearable psychological distress associated with their experiences and trusting that their vulnerability, hurt and pain will be appropriately and sensitively handled through the relationships with others around them. Hardly an easy task. Especially given that relationships were the original source of their suffering.

Gabor Mate, renowned addiction expert and author of ‘In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts’, writes:

To expect an addict to give up her drug is like asking the average person to imagine living without all her social skills, support networks, emotional stability, and sense of physical and psychological comfort. Those are the qualities that, in their illusory and evanescent way, drugs give the addict.

Gabor Mate

A critical element of working with change is to help parents see some of the benefits that could be derived from changing.

This functions as a bridge between where they are and where they want to be, and the support services that would enable them to take on that journey.

This is very different from telling them what they need to change, how they need to change, and making expectations for them to engage in the support service we’ve identified.

There are three steps to this. We have listed them below, click through to read each step.

We need to seek to understand how the behaviour helps them, either currently or in the past.

Most behaviour, even behaviour that seems illogical, self-destructive, or harmful to others, has an underlying self-protective function.

Connecting with this underlying reason requires curiosity and empathy. To be done effectively, it requires a dispense with all judgment, even if only momentarily, to discover how this behaviour has served them.

We need to explore whether they want to do anything about it, and if they do, what they imagine are the benefits if they could. Almost any behaviour, even harmful behaviour, often has advantages and disadvantages.

So, it is common for parents to alternate between giving reasons for and against change. As social workers are under pressure to bring about change, the risk here is that we jump in to list all the reasons why they need to change, including adding to the list of disadvantages they haven’t considered.

Often this automatically makes parents more defensive, and they close down. Therefore, try to focus on their desire to change and help them think about some of the advantages of them changing, and then link their self-identified desires with support services that might support them with their journey.

Motivational Interviewing provides excellent ideas and tools to navigate these conversations about change successfully. See ‘Motivational Interviewing for Working with Children and Families’ by Forrester, Wilkins and Whittaker.

Third, this conversation is then nested within broader conversations about consequences, which are shared in a particular way. First, it is not a punishment rather an explanation of consequences. Secondly, it is framed as a choice. It might be a very limited choice with few options, but it is a choice, nonetheless.

We can’t make people change, but we can help them think about their goals and identify the support that will help them.

There are three elements that underpin rights-based social work that we have covered so far:

- We must uphold the child's rights and manage these with the rights of the parents. When the child’s right to protection supersedes the parent's right to private family life, we explain these processes transparently and humanely. Social work is a rights-based profession.

- We can endeavour to collaborate with the parents, build upon their strengths, establish shared goals, and allow them to determine how they will achieve the goal of increasing child safety.

- We can’t make parents change, nor can we force them to access support services. But we can have a conversation with them where they are provided the space to consider the possibility of change.

When we think about our work, the challenge of building a relationship with parents in a child protection context cannot be underestimated. It requires courage, humility, and tenacity.

It is tough, emotionally taxing, and intellectually challenging. Yet, as many of us know, it can be profoundly rewarding, enjoyable, and a privilege. And, as pointed out by Andrew Turnell in a paper he wrote in 2004.

Child protection workers do in fact build constructive relationships, with some of the 'hardest' families, in the busiest child protection offices, in the poorest locations, everywhere in the world. This is not to say that oppressive child protection practices do not happen, or that sometimes they are even the norm.

Andrew Turnell

Our personal values

We hear a lot about social work values, but do we contemplate our own values as individual practitioners and support our staff in doing the same?

Do we think about what type of social worker would you want knocking on your door if you were traumatised, exhausted, struggling with addiction or in a violent relationship? If you reacted with fear, anger or avoidance, how would you want a social worker to treat you?

We end with a quote by Patricia Crittenden, who writes:

Can we respond with mercy – even grace – when faced with the harm that some parents create? Can we acknowledge ignorance when we don’t understand and don’t know what to do, particularly when we don’t understand the terrible tragedies humans impose on each other? Can we comfort those who have destroyed their world and that of others, even when we don’t understand and we protect them from themselves?

Patricia Crittenden

Building relationships in child protection requires identifying values we want to uphold, irrespective of the conditions, and to do that effectively would benefit from us thinking more explicitly about them.

Crittenden, P.M. (2016) Raising Parents: Attachment, Representation and Treatment,(2nd ed.) Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge

Forrester, D., Westlake, D., & Glynn, G. (2012). Parental resistance and social worker skills: Towards a theory of motivational social work. Child & Family Social Work, 17(2), 118-129.

Mate, G (2018).In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts. Close Encounters with Addiction. London, Vermilion.

Turnell, A. (2004) Relationship-grounded, safety-organised child protection practice: dreamtime or real-time option for child welfare? Protecting Children, 19(2): 14–25.

Professional Standards

PQS:KSS - Relationships and effective direct work | Communication | Child and family assessment | The role of supervision | Abuse and neglect of children | Promote and govern excellent practice | Effective use of power and authority | Purposeful and effective social work | Lead and govern excellent practice | Developing excellent practitioners

CQC - Effective | Caring | Responsive

PCF - Values and ethics | Rights, justice and economic wellbeing | Critical reflection and analysis | Intervention and skills

RCOT - Service users