Photographs bring together verbal and visual communications systems, offering a snapshot of a single moment in time.

In 2019, I participated in a study exploring the experiences of young people who had lived in a home where there was domestic violence or abuse. Now a researcher myself, I’d like to share what I learned from taking the participant’s perspective, and about photo elicitation - a method of using photographs to explore the impact of trauma.

I was 30 years old, but the researchers welcomed an older ‘young person’ contributing to their study, in the knowledge that childhood adverse experiences or trauma carry the risk of long, or forever effects (Dye, 2018; Herzog and Schmahl, 2018). Having adults involved gives researchers an opportunity to identify the longer-term impact of trauma and allows adult survivors to benefit from engagement in research. As Gill Hague suggests, adult child survivors are ‘still forgotten, still hurting’ (Hague et al. 2012).

Following the first part of the study, I was asked to send the researchers digital copies of photographs that reflected my experiences of living in a violent/abusive home. The aim was to gather what could visually be represented, including what helped us to cope.

The study information sheet specified that the researcher would not look at the photographs before the interview, so the discussion of the photos could be guided by the participants, to give us ownership of our personal experience (cf. Hopkins and Wort, 2020; Liebenberg, 2018).

The image below shows one of the photos I selected, which is of a picture given to me by a young girl I was supporting who had moved into a woman’s refuge with her mum. This picture reminded me of ones I drew for my mum when I was young. Children’s pictures are telling. I kept this one because the young person and I are alike in our hopes for brighter days, a happy home, and a peaceful environment watching nature (the beautiful pink love butterfly).

A drawing used in the study.

There can be an element of apprehension when it comes to discussing lived experience of trauma. It doesn’t matter how many times it’s been discussed; reliving past or ongoing trauma is, in effect, laying bare the raw and painful realities in our lives.

For some, it can be easier talking to a stranger, and the study instructions made clear that participants could change their mind at any point, given the difficulty of discussing such experiences:

Just to remind you, there is no obligation to take part, and I would encourage you to do so only if you feel you are able to discuss your experiences. For some people, it is difficult to do so, and I would encourage you not to take part if the emotions of your experience are too raw. Should you take part and feel upset, you are free to withdraw from the study at any time without having to provide a reason for doing so.

Information provided for participants

This made me appreciate why truly ethical research requires more than simple adherence to the prescribed criteria. It’s about instilling confidence in, and having compassion for, the participants by using warm language.

Like the researcher, prior to our interview I did not revise the photos I’d submitted or what I would say based on what they meant. I had found them on my computer, and they portrayed aspects of my life which provided me with elements of healing and hope for a better future.

In guiding the researcher through my pictures, I realised that I had not fully applauded myself in how far I had come, transforming the research participation into an epiphany.

I did become emotional when it came to one photo, which portrayed my mum and myself coming together to tell each other that we wanted to have better memories from now on. The researcher asked if I was okay and said that we could stop, but I wanted to continue.

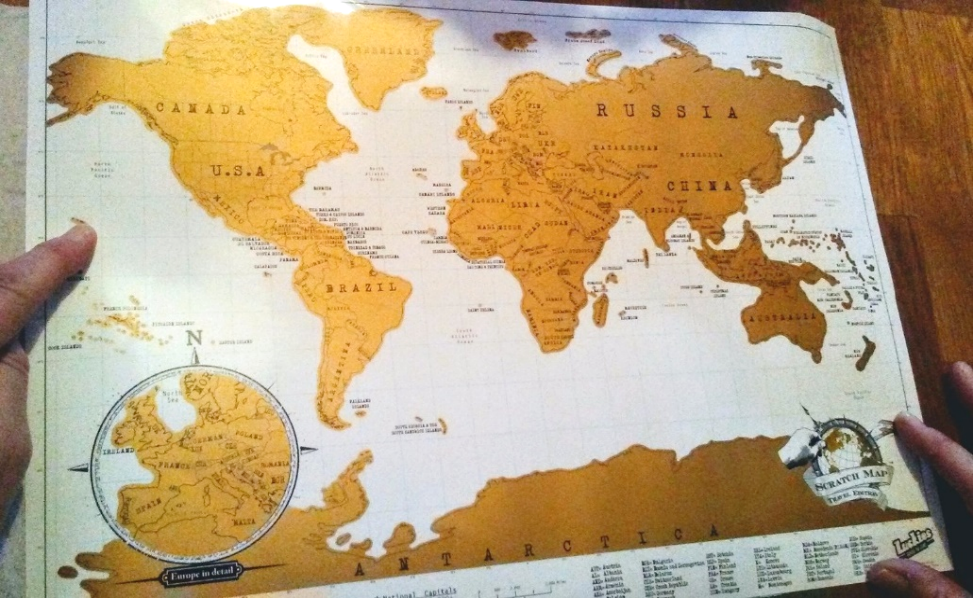

The below image of the map was a Christmas present so I could mark all the places I had visited thanks to her stories.

World map as used in the study.

When my mum was younger, she travelled around the world. Her stories of her travels allowed us to be transported somewhere else, at the same time reminding mum of who she was before meeting ‘him’. Mum’s stories of people, cultures and places encouraged me to take an interest in the world.

Overall, the experience of talking to the researcher about the photos allowed me to remember what had been, and where we were now, through moments of deep connection with my mum.

It is a way of joining efforts to address the injustices in the ways victims of domestic abuse are treated, and through moments of joy in discovering my own sense of self.

Young people should be given opportunities for their own development and ensure every contribution is credited. Anonymity can protect the participant, but some may feel it denies their voice/contribution.

The experience was not only beneficial to me in understanding the generative power that lies within creative methods, but it has helped me to think more about how we centre people when we want to carry out research, particularly in relation to trauma and experiences of domestic abuse.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Dr Jade Levell for the feedback on this article and for being a fierce advocate for adult child survivors of domestic violence and abuse.

Dye, H., 2018. The impact and long-term effects of childhood trauma. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 28(3), pp.381-392. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10911359.2018.1435328

Hague, G., Harvey, A. and Willis, K., 2012. Understanding adult survivors of domestic violence in childhood: Still forgotten, still hurting. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Hague, G., Harvey, A. and Willis, K., 2012. Understanding adult survivors of domestic violence in childhood: Still forgotten, still hurting. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=EFgSBQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Herzog, J.I. and Schmahl, C., 2018. Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the lifespan. Frontiers in psychiatry, 9, p.420. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00420/full

Hopkins, L. and Wort, E., 2020. Photo elicitation and photovoice: how visual research enables empowerment, articulation and dis-articulation. Ecclesial practices, 7(2), pp.163-186. https://brill.com/view/journals/ep/7/2/article-p163_163.xml

Kara, H., 2022. Doing research as if participants mattered. Impact of Social Sciences Blog.

Liebenberg, L., 2018. Generating Findings That Are Able to “Stand on Their Own Feet” Exploring Innovations in Elicitation Methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), p.1609406918801666. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/115838/1/impactofsocialsciences_2022_07_11_doing_research_as_if_participants.pdf