Using group supervision

Part of Reflective Supervision Hub > Practice Supervisor resources

Select the quick links below to explore the key sections of this area for Using group supervision.

Benefits of Key elements Online group supervision Three models Preparing to use

Role of the Practice Supervisor Conflict in groups Power and difference Final reflections

Introduction

Group supervision can take place online or face to face. It can help teams to:

- Reflect in depth on complex problems.

- Pool and apply knowledge and skills.

- Challenge individual perspectives (a group’s diversity in terms of gender, age, ethnicity, and experience will provide different perspectives).

- Explore the skills, processes and dynamics needed in practice.

- Provide a safe space to share feelings.

- Build relationships and reduce isolation.

- Develop a shared language, values, and culture.

For group supervision to be effective it needs to include a mutually agreed purpose, focus and structure; trusting relationships between participants and facilitator and strong facilitation by someone with an understanding of the group processes being used. Adapted from Earle et al. (2017).

This chapter explores how we can embed effective group supervision within practice. The content within this chapter has been adapted from publications developed as part of the Practice Supervisor Development Programme (PSDP) funded by the Department for Education.

-

Using group supervision in children’s social care by Guthrie (2020).

-

Bells that ring: an overview of a systemic model of group supervision by Partridge (2019).

-

The reflective case discussion model of group supervision by Ruch (2019).

-

Online group supervision by Sutton (2022).

The benefits of group supervision

It is not always possible to reflect in-depth on practice during individual supervision. One way to address this is by using group supervision to support practitioners:

- Group supervision allows practitioners to hear different voices and perspectives about practice (Bostock et al., 2019).

- Participants can discuss suggestions with, and get feedback from, both peers and supervisors (Kadushin and Harkness, 2014).

- Group supervision can challenge practitioners’ assumptions about practice, helping them to become more aware of blind spots and biases (Staempfli and Fairtlough, 2019, Lees and Cooper, 2019).

- It also offers a space to hold important conversations about social justice, ethics and anti-racism (Kadushin and Harkness, 2014 in Sutton, 2022).

- Practitioners find group supervision to be emotionally containing, and supportive which helps to reduce feelings of burnout (Staempfli and Fairtlough, 2019, Lees and Cooper, 2019).

- Sharing anxieties, challenges and uncertainties with others is helpful in planning next steps when practitioners feel stuck or unclear (Bogo et al., 2004).

- Jointly engaging in reflective group discussions helps teams become more supportive and cohesive (Bailey et al., 2014 and Wagenaar, 2015 in Staempfli and Fairtlough, 2018, Lees and Cooper, 2019).

- Developing a better understanding about other people’s roles (both within the organization and the wider system) strengthens organisational identity and helps practitioners to work together more effectively (Lees and Cooper, 2019).

- Group supervision can support practitioners to become more reflective and confident in their practice (Tietze, 2010 in Staempfli and Fairtlough, 2019, Ravalier et al., 2023).

- It can be used to actively rehearse and role-play conversations and plan next steps in practice (Bostock et al.,2019).

- Conversations about role boundaries in group supervision help practitioners develop a stronger sense of professional identity (DiMino and Risler, 2012).

-

What might be the benefits of group supervision for your work context?

-

What do you hope group supervision might offer your team which is not already offered by individual supervision?

-

How might you explain these benefits to your team when you introduce the idea of group supervision?

Key elements of group supervision

There are many models of group supervision. They tend to have more similarities than differences. Most are designed to ensure:

- Discussion is respectful to both the practitioner and people drawing on care and support.

- The process is transparent, and everyone’s contributions are

- The structure helps people reflect.

(Earle et al., 2017)

They usually include the following key features:

-

A presenter's description of a dilemma or difficult practice situation.

-

An opportunity for the presenter to reflect on the ideas they have heard.

-

An opportunity for group members to ask questions and share their ideas.

-

Guidance for group members about different roles (facilitator, presenter, group member).

Keeping to the structure is important, especially at the beginning while everyone is getting used to it, as this:

- Supports sharing ideas and communicating in ways which would be unlikely to happen within a free-ranging discussion.

- Helps group members feel calm and safe within the group without being too emotionally connected to the discussion.

- Creates opportunities for everyone to express different thoughts, to notice their feelings and to ask questions which may not have occurred to them outside of group supervision.

If the facilitator can help everyone follow the structure of the supervision model, it is more likely to be successful.

(Lees and Cooper, 2019)

Online group supervision

Most models of group supervision can easily be adapted for use online. Online group supervision means using an online conferencing platform such as Microsoft Teams, Zoom, Google Meet etc., to engage in structured group discussion about practice.

Online group supervision offers some significant benefits:

Feelings of isolation and anxiety about practice can increase when teams don’t meet regularly in person. Supporting practitioners to feel emotionally connected and contained has become more significant as hybrid and home working are now common and online supervision can help address this

(Research in Practice, 2020)

It can help team members who find it difficult to meet in person develop more effective working relationships. For example, teams based in different locations, who cover a large geographical area or who work closely with multi-agency partners.

(Rushton et al., 2017)

Remember that any conflicts that may arise in online group supervision can be exacerbated in a virtual context. Emotional cues can be harder to read, faces are close (which magnifies expressions that would seem more subtle in a meeting room context), and technical difficulties may cause tempers to fray (Lambell et al., 2022). This requires care and attention by the facilitator.

It is useful to consider some extra ground rules, these might include:

- Joining the meeting five minutes early to iron out any technical issues before the discussion starts.

- Cameras on (generally). If working at home, and personal life interrupts, cameras may temporarily be switched off.

- Mute when not speaking.

- Wearing headphones to maintain confidentiality if working in a shared space.

- Raising a digital hand and waiting to be invited by the facilitator to speak.

- Only using the chat function for brief comments rather than substantial additions to the discussion.

- Agreeing that silence is OK. Everyone needs time to think.

- Agreeing that everyone will contribute, and that the facilitator may ask someone for their view if they haven't spoken yet.

- Agreeing how the group can signal if a comfort break is needed.

Adapted from Sutton (2022).

Three models of group supervision

Time: ⏲ 60 minutes | Format: online or in-person

Adapted from Staempfli (2019). Intervision is a peer-led model of group supervision. The various roles are shared within the group and members swap roles from session to:

- This can be a helpful model to begin with if you are unsure about facilitating a group process.

- Basic principles: one person presents, one person facilitates, one takes notes, and the rest reflect as a team on the presented At no point is there direct interaction between the reflecting team and the presenter. The facilitator guards ground rules and time.

Time: ⏲ 45-60 minutes | Format: online or in-person

Adapted from Ruch (2019) and Sutton (2022). In this reflective case discussion model of group supervision participants discuss a practice scenario in depth and reflect on their responses to this.

- The facilitator, usually the practice supervisor, actively takes part in the discussions to prompt everyone to share their reflections as well as keeping the group on task and on time.

- Basic principles: a presenter outlines a challenge from practice, the group then discusses this with the presenter listening. In the final round of discussion everyone contributes and reflects on learning. The facilitator prompts the group to be reflective and curious throughout.

Time: ⏲ 45-60 minutes | Format: online or in-person

Adapted from Partridge (2019). Bells that ring model of group supervision is informed by systemic and strengths-based approaches and supports a curious and inquisitive approach to exploring multiple perspectives.

- Group members take up different roles so that different perspectives can be explored.

- Practice supervisors are actively involved in allocating roles and keeping the group on time as they move through the different stages of discussion.

- Basic principles

A presenter has a conversation with a consultant with a separate observer group listening. An action planner notes any decisions or tasks arising from the discussion. - Watch the short film below to see this mode of group supervision in action.

'Bells that ring'

Alongside the model guide above, watch this short film to see this mode of group supervision in action.

Length: 12 minutes.

So we are going to have a go at the Bells That Ring group supervision process. I'm going to take the role as of the supervisor, so I'm going to allocate roles to you and you've got a card just to help remember what you're supposed to be doing, although I'm sure you know already.

So Michelle, you're going to be the consultant. I'm going to be the supervisor. I'm probably going to take the role of action planner as well. You're going to be the observer. Esther, you're going to be the presenter. And here you go for, um, those are the reflections when we get to them and there's the process down there.

Ok. So let me tell you a little bit about the case. 5-year-old Ali fell out of a window in his parents' home and as a result, was removed originally. Went to stay with his aunty, his father's sister, but I guess because not enough was known about the paternal family, e ended up in foster care for a while and was returned home.

His brothers were also removed very briefly. There is an ethnically mixed parenting. Couple of... both young parents and mum is white British and converted to Islam some years ago when she was with her oldest son's father, her previous relationship.

So do you want to kick off for about five minutes? Five, 10 minutes, Michelle?

So Esther, what is it you would like us to like help thinking about today?

I guess in thinking about this family, I'm just aware that I sometimes feel a lone voice in the system who are considering risk with greater anxiety than I am. So I'm just wondering if my alliance with the mother is preventing me seeing risk.

What might you have heard that tells you that they feel, think this way?

I've certainly heard from all the professionals in schools that they are worried and they feel I'm not attending to their worries enough.

Yeah, that's what have they said. They're worried that these are parents that can't keep their children safe. They're worried that they can't engage the parents in conversations about their worries. They're worried that because of the history and what happened to Ali, the same might happen again, that there's carelessness, neglect around.

What are your thoughts, just in general about the family? How, how do you experience them?

I experience... I've increasingly experienced the mother as thoughtful, reflective, worried, concerned. She's also very good at challenging this system at what she feels is racism. Um, and so sometimes that means she doesn't present the best side of herself with professionals.

If you look at the genogram guys, you'll see that all five children are at different schools and nurseries. So there are two professionals from each school and nursery who are white, British women and have a particular view perhaps about Kelly the mother.

Michelle and Esther, thank you. It is time to hear from the reflecting team. So I'm going to ask you to talk between yourselves and to try and avoid making any eye contact with them so they don't feel they've got to respond to you. So they can just be free to think. And if you kind of share your thoughts for about 5, 7, 8 minutes.

I think what really stuck out for me was thinking about how Esther saw the parent as a partner, as somebody they were working closely with and really building up that relationship with and how they… it seemed clear that the professional network maybe had a very different view as to how they were positioning the parent, I suppose. And it made me think a little bit about how the sort of the national context at the moment is thinking about risks slightly differently. Maybe trying to think about contextual risk as well as risk within a family, and how the child protection system for a long time now has been the parent with their deficit. And we've kind of got a little bit stuck maybe in thinking about that. And I really liked how Esther was able to sort of be quite brave and say, you know, no, we're going to… we're going to treat this parent as the thoughtful, reflective person who's… actually evidenced with her, the conversations that she has had.

Yeah. And I felt that the theme of and ideas of Kelly's strength that Esther had seen - this strong, relatively young female mother of five, woman, really, really getting her… really fighting for what she felt that was right for her family and her voice not being heard. And actually the ideas of what could Esther do to help her get her voice acknowledged and listened to? I felt very positive about that and I felt it was really encouraging. And the idea that there could be change. And actually with a bit of further thought between the two, the partnership, this new partnership, this alliance, changes could happen.

Thank you everybody. We are going to go back to Michelle and Esther. And Michelle, it's your chance to see what's kind of stuck for Esther out of that conversation.

So Esther, thoughts to how you experienced all the feedback that you got?

It gave me a very nice warm feeling. I felt very validated. It was really nice to hear colleagues notice and appreciate what I think I'd been doing. So you know, that was really, really nice.

Was there anything in particular that resonated with you?

Um, I really like the idea that seems to be developing in my mind of being… helping Kelly promote herself in the best possible way and being a bit of a mediator between the concern in the professional network and the lived kind of reality that I'm seeing, which makes, makes my anxiety lessen a bit.

Is there anything else that you would've liked us to have attended to that we didn't?

I realised that when I presented this family, I didn't talk a lot about the men. And so maybe it would've been interesting to think about the role in the place of the father that's living with Kelly at the moment and the father of the older two that lives in Birmingham.

Now it's the chance for us to think about what things we might want to take forward from this discussion. And I'm the role of action planner, so it's my responsibility to make sure that we've got some actions coming out of this supervision session. I'm wondering what thoughts people have got? There was a really rich conversation about sort of, the way that Esther carefully and thoughtfully thinks about the family and we sort of talked about whether or not… what would it be like if Kelly was witness to that. Yeah? But also, what would happen if those other professionals were witnessing Kelly engaging in that conversation, hearing it and reflecting about that? Because I guess the relational element seemed to be missing at times with the other professionals. And it would be lovely to be able to think about how Esther could orchestrate something like that happening. Yeah? Anyone got any thoughts about that?

No, I mean, I think that sounds like a brilliant idea and I mean it could even be on Kelly's terms. It could be somewhere where Kelly feels comfortable.

Yeah, it could be. And I think just, you know, what you were talking about, what we heard Esther talking about it being a very big network. You know, we could be speaking to Kelly about who she'd feel comfortable [having] there, the kind of people that she really wanted to sort of think about. You know, they could talk together first about who she wanted to be there and who it would be useful in developing a different relationship with and reframing that relationship.

Mm-hmm. I think in a way that's a really good idea. I don't think that Kelly would be phased. I think with some support she'd be quite happy in a way to present another side of herself and have the opportunity to do that. So I think it, it's worth me exploring with her.

So it sounds like one of the action points coming out of our conversation is finding ways to demonstrate to other professionals the Kelly that you've met, and to begin to do that systematically with other parts of the network. Does that make sense?

So shall we move into thinking about what we've learned from doing this today? You know, what's it been like being in the position you're in? You know, what kind of learning points do you think that we could pull out or any theory practice links for that matter? I really appreciated observing, you know, the conversation, but especially the questions you were asking Michelle. Because I think you don't often get the chance just to sit there and listen obviously to the content of the conversation and try to think about creative ways to think about some of these dilemmas. But just to hear really good, thoughtful questioning that teases things out. It was, yeah, it was, it was brilliant.

Yeah. I was curious about whether Esther had had had any of these thoughts? Before whether or not her… um, the ideas of helping Kelly have a voice and helping other people see what she sees in Kelly. Whether that's been in her mind? And also it made me feel that… I wondered how Kelly would feel about knowing that we were, we had all been sharing her story and thinking about her in this way?

I was initially absolutely terrified about revealing my casework to my peers, my supervisor. But actually I found it exceptionally helpful. One, I found it validating and it's… so thank you very much for that. So I feel like I'm on the right track and it's given me some new ideas. It's made me more curious about the possibilities and I'm very grateful for that. Thank you everybody.

Each model of group supervision has strengths. In choosing a model you might want to consider:

-

What do I aim to achieve in offering group supervision?

-

Which model seems to offer a good fit with the culture of my team and organisation?

-

Which of the models seems to fit with my aims for learning in the group?

-

Which model feels the easiest to implement?

Preparing to use group supervision

We recommend that you talk to your team about why you are introducing group supervision and your hopes about how it might contribute to improving practice.

Once you have decided on a model, ensure that everyone involved is clear about how it works. It can help to share the structure with the group and have the steps and timings clearly laid out so that everyone can follow them. This takes some pressure off the facilitator and makes the session feel more collaborative. Before you begin to use group supervision, have a joint discussion and agree ground rules for working together.

We are aiming to:

- Create an open, non-judgmental space and value curiosity.

- Hear different perspectives and value diversity.

- Pay attention to how we communicate so that we are respectful of each

- Listen with curiosity and an open mind without interrupting when it is not our turn to speak.

- Pay attention to who has or has not spoken (including yourself) and allow others who have not yet expressed their ideas to speak.

- Be mindful of differences within the group regarding culture, ethnicity, race, age, experience, and gender.

Staempfli (2019)

Right from the start, it is useful to think about how you will know whether group supervision is successful. One way you can do this is by agreeing how you will evaluate group supervision with the team.

- Monitoring attendance levels: A low level of attendance may indicate that people are not finding it useful. This can be a helpful prompt to talk to the group about the barriers they are experiencing.

- Regular reviews: This need not be time consuming or complex. Perhaps use the last five minutes of the sessions to ask group members how they have experienced the group?

- Impact on practice: Collect examples during group supervision about how the process has impacted on practice.

- Feedback: Check out with the group whether they have noticed any improvements in resilience or team work as a result of using group supervision. If you are a practice supervisor, you are well-placed to notice these things, so also ask yourself what changes you are observing.

- Which skills of group supervision are already areas of strength for you?

- What needs to happen for you to feel ready to give it a go?

- Which skills of group supervision would you like to develop further?

- Who can be your partner in this? Do you have a colleague who might introduce group supervision in their team at the same time, so that you can share experiences and support each other's learning?

The role of the practice supervisor in group supervision

As practice supervisor you play a key role in the success of group supervision with your team.

While the opportunity to learn from the perspectives of others can be valuable, it also requires people to share their thoughts, feelings and uncertainties with others in the group. This can make people feel uncomfortable. Feelings of shame, vulnerability and inadequacy arising from this get in the way of learning and reflection.

A group is likely to take its lead from the supervisor, so it is important that you model how to create safety, acknowledge uncertainty, keep boundaries and be curious. In their study of the use of group supervision with student social workers, Bogo et al. (2004) found that the students’ rating of their supervisors’ competence was the single biggest predictor of their satisfaction with their experience.

The students appreciated supervisors who:

- Gave clear expectations about the process and steps of the supervision.

- Used modelling to promote a constructive learning climate.

- Encouraged supervisees to develop a healthy group process.

- Intervened if conflicts or difficulties occurred.

- Offered timely and constructive feedback.

- Supported students to learn about common patterns of group process and group dynamics.

Conflict in groups

Group supervision can also give rise to conflicts between group members who may be at very different stages of emotional and professional development and experience. This means that you may need to be prepared to enforce boundaries. For example, to offer direct feedback to a person who is taking up too much airtime, or to step in if there is conflict or a group rule has been broken.

Sharing multiple perspectives usually prompts groups to consider different ideas and to challenge each other. But groups can struggle with this and prefer consensus rather than looking for alternative explanations or views. This is known as ‘groupthink’ (Munro, 2008).

To counter this, group supervisors need to be able to reflect in action during the group’s conversations and to encourage the group to notice which ideas they are open to and which ideas they may not have considered. It can also be helpful to prompt the group to consider how they are working together and to explore if disagreement feels challenging.

-

How do you feel about exploring and resolving conflict in group supervision sessions?

-

How able are you to reflect ‘in action’ and to notice when a group might be engaging in ‘groupthink’?

-

What is your experience of maintaining emotional safety when a person feels criticised or shamed in a group?

-

Who can support you in further developing these skills?

Attending to power and difference

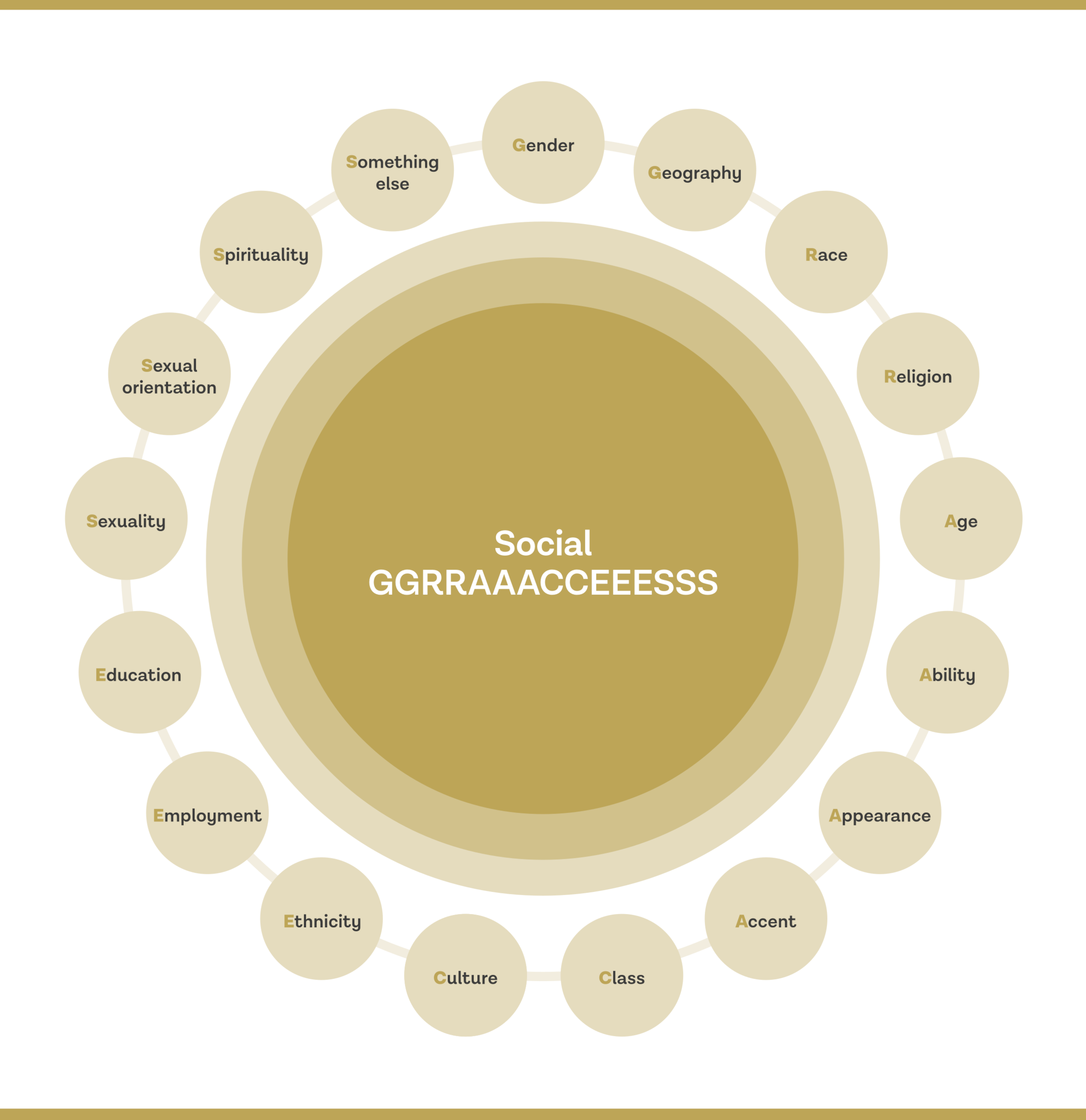

It is important to pay attention to issues of power and difference in group supervision based on individuals’ social GGRRAAACCEEESSS.

This is a model which describes aspects of personal and social identity which include gender, geography, race, religion, age, ability, appearance, class, culture, education, ethnicity, employment, sexuality, sexual orientation and spirituality. (Burnham, 2013)

If you have read other sections in this resource hub you may have come across social GGRRAAACCEEESSS already. The social GGRRAAACCEEESSS is a flexible tool that helps us explore the impact of power, discrimination and disadvantage. It can be used in several ways to support supervision practice.

Focusing on the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS is a useful way of embedding conversations about power and difference into group supervision discussions.

Differences based on identity and social power can sometimes become apparent in overt ways. For example, if a group member makes an assumption based on a stereotype.

Issues of power and difference can also have influence in more subtle and less visible ways. Some group members may have had previous experiences of not being listened to or being given space in groups to speak up and may find it hard to do so in group supervision.

Other group members, who have different life experiences which have given them opportunities to speak and be heard, may find it easier to contribute so that their voices are heard more often. This is known as ‘voice entitlement’ (Boyd, 2010).

Group supervision can be a very useful environment to reflect on these themes.

Group supervision is a valuable space in which to discuss issues of inclusion, power, identity and difference. This can break what is sometimes called the ‘loud silence’ (Crehan and Rustin, 2018) around inclusion, equality and diversity.

Loud silence refers to when group participants are anxious about these discussions and do not speak up.

Sutton (2022, p.6)

- How comfortable are you with conversations about social GGRRAAACCEEESSS? Are there some themes you feel more comfortable with and others with which you feel less comfortable?

- How much have you been able to reflect on your own social GGRRAAACCEEESSS and how they position you in relation to the members of the group, or the people with which your team works?

- What experiences have you had of discussing issues of power and difference in groups?

- How able do you feel to initiate conversations about power, difference and sameness within the group?

- Who can support you in reflecting more on these themes?

- Do you know of anyone else who is interested in group supervision in your organisation that you can connect with to share ideas and progress with?

![]() What shapes you as a practice supervisor - If you would like to reflect more on your own experience of the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS, this tool (from Building effective supervision relationships) provides a series of guided questions.

What shapes you as a practice supervisor - If you would like to reflect more on your own experience of the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS, this tool (from Building effective supervision relationships) provides a series of guided questions.

Final reflections

The questions below are helpful prompts for you to use privately, or in discussion with a trusted colleague, as part of your preparation for introducing group supervision. Reflecting on your strengths and areas for development can help you to feel more confident about using group supervision.

-

What experiences have you had of group supervision? What emotions were you left with?

-

How might those emotions affect you now as a facilitator?

-

How do you feel about introducing group supervision into your team?

-

How open are you to hearing feedback from the group, reflecting on it and sharing your own learning?

-

To what extent do you need to have your expertise acknowledged by the group?

-

How might you feel about being seen to get something wrong in the group?

-

How comfortable are you with silence?

-

How do you respond to conflict between group members? Do you experience an urge to fix it or are you comfortable with allowing group members to sit with it?

Bogo M., Globerman, J. and Sussman, T. (2004). Field instructor competence in group supervision: Students’ views. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 24, 199-216.

Bostock, L., Patriz, L., Godfrey, T., Munro, E. and Forrester, D. (2019). How do we assess the quality of group supervision? Developing a coding framework. Children and Youth Services Review,100, 515-524.

Boyd, E. (2010). ‘Voice entitlement’ narratives in supervision. Cultural and gendered influences on speaking and dilemmas in practice. In Burke, C. and Daniel, G. (ed) Mirrors and reflections. Processes of systemic supervision (2010). Routledge.

Burnham, J. (2013). ‘Developments in Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS: visible-invisible, voiced-unvoiced’. In Krause, I. (ed) Cultural Reflexivity (2013). Karnac.

Crehan, G., and Rustin, M. (2018). Anxieties about knowing in the context of work discussion: Questions of difference. Infant Observation, 21(1), 72–87. DOI:10.1080/13698036.2018.1539338

DiMino, J. L. and Risler, R. (2012). Group supervision of supervision: A relational approach for training supervisors. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 26(1), 61-72.

Earle, F., Fox, J., Webb, C. and Bowyer, S. (2017). Reflective supervision: Resource Pack. Research in Practice.

Guthrie, L. (2020). Using group supervision in children’s social care. Research in Practice

Kadushin, A. and Harkness, D. (2014). Supervision in Social Work: 5th ed. Columbia Press.

Lambell, C., Slinn, E., Shand, S., Wild, J., and Sutton, J. (2022). Digital Inclusion: Using digital technology positively and safely. Research in Practice.

Lees, A. and Cooper, A. (2019). ‘Reflective practice groups in a children’s social work setting - what are the outcomes, how do they work and under what circumstances? A new theoretical model based on empirical findings.’ Journal of Social Work Practice, 35(3), 1-17.

Munro, E. (2008). Effective Child Protection (2nd ed). Sage.

Partridge, K. (2019). Bells that ring: an overview of a systemic model of group supervision. Research in Practice.

Ravalier, J. M., Wegrzynek, P., Mitchell, A., McGowan, J., Mcfadden, P. and Bald, C (2023). A Rapid Review of Reflective Supervision in Social Work, The British Journal of Social Work, 53(4), 1945-1962. DOI: 10.1093/bjsw/bcac223

Research in Practice (2020). Learning from Lockdown: Final Report. Research in Practice.

Ruch, G. (2019). The reflective case discussion model of group supervision. Research in Practice.

Rushton, J., Hutchings, J., Shepherd, K. and Douglas, J. (2017). Zooming in social work supervisors using online supervision. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 29(3), 126–130. DOI: 10.11157/anzswjvol29iss3id254

Staempfli, A. (2019.) Intervision model of peer led group reflection. Research in Practice.

Staempfli, A. and Fairtlough, A. (2019). ‘Intervision and professional development: an exploration of a peer-group reflection method in social work education’. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(5), 1254-1273.

Sutton, J. (2022). Online group supervision. Research in Practice.

Reflective supervision

Resource and tool hub for to support practice supervisors and middle leaders who are responsible for the practice of others.