Supporting critical analysis

Part of Reflective Supervision: Learning hub > Practice Supervisor resources

Select the quick links below to explore the key sections of this area for Supporting critical analysis (CA)

Supporting decision-making in supervision Supporting practitioners to reflect Supervision tools to support critical thinking

Using questions strategically in supervision Final reflections

Introduction

- Practice supervisors play a key role in supporting practitioners to critically reflect on their practice in supervision.

- When practitioners critically analyse their work, they draw on different forms of evidence and knowledge and reflect on different perspectives to make professional judgments about what to do next.

- Practitioners need to be able to think critically about how power, privilege and discrimination can influence their interactions with, and decisions about, people who draw on care and support.

- Structured supervision tools can be helpful in promoting critical analysis.

- Over time, supervisors sometimes forget or lose their ability to ask questions that facilitate reflective and critical thinking in supervision.

- The interventive interviewing model can help practice supervisors ask curious questions that facilitate supervisee’s critical analysis skills.

The content has been adapted from publications developed as part of the Practice Supervisor Development Programme (PSDP) funded by the Department for Education.

- Using the five anchor principles in supervision by Domakin and Sturt (2019).

- Using a systemic lens in supervision by Guthrie (2020).

- Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS and the LUUUTT model by Partridge (2019).

- Safe Uncertainty by Williams (2019).

- Interventive Interviewing by Usiskin Cohen, McNamara and Williams (2019).

Using critical analysis to support decision-making in supervision

Practice supervisors play a key role in supporting practitioners to critically reflect on their practice and make decisions about what to do next.

When practitioners critically analyse their work, they are able to:

- Draw on different forms of evidence and knowledge.

- Reflect on different perspectives, opinions, and areas of potential bias.

This is important because:

- It supports practitioners’ ability to make professional, well reason judgments that are ethical and supported by evidence.

- Working with people who draw on care and support often involves complexity and uncertainty. There are rarely clear solutions about what the best course of action is (Sidebotham et al, 2016 in Wilkinson, 2020).

- A lot of information can be generated by practitioners, sometimes from a range of sources. It can be hard to make sense of what this all means.

- Without analysis and critical thinking, practitioners may find it hard to move from gathering information to forming professional judgments.

- It helps practitioners understand the implications of the decisions they make.

Adapted from Earle et al. (2017)

What do supervision discussions that support critical analysis look like?

You might be asking yourself what the difference is between reflection and critical analysis in supervision. The easiest way of answering this is by saying that reflection supports critical analysis.

Have a look at the following two areas that focus on reflective discussions and the shift from reflection into critical analysis.

Reflective discussions that support critical analysis help practitioners to:

-

Explore assumptions, power relations or wider social issues affecting their work. For example, culture, disadvantage and discrimination (Wilson et al., 2018, Ryde et al., 2018).

-

Reflect on their emotional reactions to practice (Ruch, 2012).

-

Consider different explanations and perspectives (Heffron et al., 2016, Julien-Chinn and Lietz, 2019).

-

Understand what knowledge is informing their practice and the limitations of this (Wonnacott, 2014).

-

Develop a clear plan about what needs to happen next and actions which are likely to produce the best results (Wonnacott, 2014).

Adapted from Earle et al. (2017)

Each area of reflection is a building block for critical analysis.

We shift from reflection into critical analysis when we consider:

-

What does all this information tell us?

-

What explanations or hypotheses can we draw from this?

-

What do we think should happen next?

-

What are we going to do and why?

Supporting practitioners to reflect on power, privilege and discrimination

Before we go further, let’s think about the importance of practitioners being able to think critically about how power, privilege and discrimination can influence their interactions with, and decisions about, people who draw on care and support.

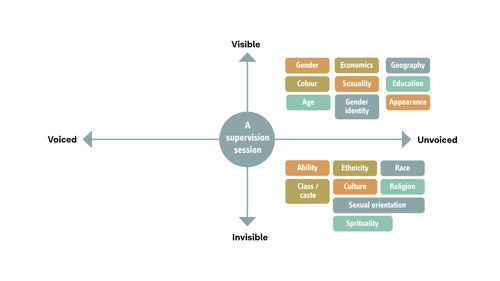

The social GGRRAAACCEEESSS is a helpful tool for this (Burnham, 2013). This is an acronym which helps us think about aspects of personal and social identity that give us less or more power in different contexts in society. The different social GGRRAAACCEEESSS are shown in the accordion and tool below.

In Building effective supervision relationships we consider how the toll can help you, as a practice supervisor, build effective supervision relationships in diverse teams (working across differences of race, ethnicity, age, class, sexuality etc.).

Here we are thinking about how reflecting on the tool in supervision can help practitioners develop greater understanding about:

-

Aspects of their life and identity where they have less or more power in society.

-

How these experiences can influence their responses to, and communication with, people who draw on care and support.

-

The impact of experiences of powerlessness, discrimination and disadvantage on people who draw on care and support.

The social GGRRAAACCEEESSS, developed by Burnham (2013), is a helpful tool to start thinking about how aspects of personal and social identity give us less or more power in different contexts in society. Adapted from Sturt (2019).

The tool captures parts of our personal and/or social identity that can be voiced or unvoiced and visible or invisible.

If you have read other chapters in this learning hub you may have come across the tool already, which is flexible and helps us explore the impact of power, discrimination and disadvantage. It can be used in several ways to support supervision practice.

(A large view of the tool can be viewed in the downloadable tool below, About the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS).

Different parts of our personal and social identity can be voiced or unvoiced and visible or invisible.

(A large view of the diagram can be viewed in the downloadable tool below, About the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS).

Talking about the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS in supervision with your supervisee can help make them more visible. For example, you could explain them in supervision and then invite practitioners to:

-

Think about their own social GGRRAAACCEEESSS and those of the people you are discussing in supervision.

-

Explore the differences and similarities and reflect on the potential impact of this.

-

Consider how these factors might affect their decision-making.

You can also use them as a prompt for your questions in supervision to build awareness of visible / voiced and invisible / unvoiced experiences.

Examples of questions for exploring power, privilege and discrimination with supervisees:

- How do you think racism impacts on this piece of work?

- What do you think this family’s religious or spiritual beliefs are?

- How might gender show in this relationship?

- How are you considering the potential impact of power differences in this relationship?

- Does this connect with any personal stories or experiences for you?

- How does your experience of the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS impact on your decision-making here?

- How do you think that XX’s experience of coming here as an immigrant has shaped them?

Adapted from Partridge (2019).

![]() Supporting practitioners to reflect on power, privilege and discrimination - This tool provides more information about the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS.

Supporting practitioners to reflect on power, privilege and discrimination - This tool provides more information about the social GGRRAAACCEEESSS.

Take a moment to pause and reflect on the information you have read in this section.

-

How might you explain critical analysis to your supervisees?

-

Is there anything you would like to do differently to support critical analysis in supervision?

Supervision tools that support critical thinking

In this section we outline three different tools and explain how to use them in supervision (tool downloads available below). They are simple to use and they can be adapted to the time you have available.

1. The five anchor principles

The five anchor principles prompt practitioners to make sense of what they know at five key points during an assessment (Brown, Moore and Turney, 2014).

They are a helpful tool for supporting analysis and critical thinking about any kind of assessment (whether formal or informal). They can be used in supervision to review work at any point in the assessment process. They are also useful for structuring analytical writing in assessments and plans.

(A large view of the assessment principles can be viewed in the downloadable tool below, Five anchor principles).

-

This is an important question to discuss in supervision at the outset.

-

Being clear about the purpose of the assessment helps practitioners to start thinking about key issues from the start.

-

Asking ‘What is the assessment for?’ is quite different from asking ‘Why are we doing the assessment?’ which can prompt a process-driven response.

Questions practice supervisors can ask:

-

What do you think the purpose of this assessment is?

-

What is your immediate response to the assessment task?

-

What sense have you made of the information already available to you?

-

What is the best way to explain the purpose of the assessment to the person(s) being assessed?

-

The idea of a story helps practitioners to understand that their job is to connect relevant circumstances, facts, and events to create a coherent narrative.

-

Stories have characters, sub-plots, twists and turns, multiple perspectives, and multiple endings.

-

There may also be more than one story depending on the perspectives of people involved.

-

Practitioners need space in supervision to reflect on the information they have gathered and think about the story that is developing.

Questions practice supervisors can ask:

-

What are the views and ideas of each person involved in the assessment?

-

What are the different stories held by different professionals about what is happening?

-

What do you think the story is?

-

What other factors might influence the story (for example: class, culture, ethnicity, immigration status, economic status)?

Once the practitioner has gathered enough information to present a story, there needs to be a focus on what the story means.

Supervision discussions now need to focus on:

-

Reflecting –thinking about what we know so far.

Where are the gaps in the story? How can we find further information?

-

Hypothesising – developing explanations about what the story is. It is not important whether hypotheses are right or wrong. Your role is to help you challenge fixed ideas and consider alternative explanations (Guthrie, 2020).

Which explanations does the information that has been gathered support?

-

Testing- to understand whether explanations are correct and if any new information needs to be gathered.

Questions practice supervisors can ask:

-

What information is disputed and why?

-

What have you not been able to find out?

-

What different explanations can we generate about what is happening?

-

Which explanation do you think is most accurate? Why?

-

Once you have reached an understanding about what the story means, the focus shifts to thinking about what needs to happen next.

-

Plans should link with the story (assessment of the situation) and the views of people who draw on care and support.

Questions practice supervisors can ask:

-

What would success look like? What are we wanting to achieve?

-

What is the most pressing thing that we need to do next?

-

What does the person(s) drawing on care and support think the next steps should be?

-

What do other professionals think needs to happen?

-

When plans and intended outcomes are clear, it is easier for everyone involved to understand them, and to review

-

If these are not making a difference, it is helpful for practitioners to reflect on why this is the case and what else is needed.

Questions practice supervisors can ask:

-

How will we know we are making progress?

-

What steps will we see along the way?

-

Have plans been achieved? If not, what got in the way of this?

-

Has our explanation of the story been confirmed or disproved?

![]() Five anchor principles - A useful tool containing further information on each principle and how this will support supervision. (adapted from Domakin and Sturt (2019).

Five anchor principles - A useful tool containing further information on each principle and how this will support supervision. (adapted from Domakin and Sturt (2019).

2. Wonnacott's discrepancy matrix

Wonnacott’s discrepancy matrix helps practitioners think critically about the different kinds of information they draw on when making decisions about their work with people who draw on care and support.

The task when using the discrepancy matrix is to categorise information into four quadrants:

-

Firm ground intelligence

-

Ambiguous information

-

Assumption-led information

-

Missing.

It is a valuable tool to use in supervision to help practitioners develop greater understanding about how reliable their information is and where the gaps are. Explore details on each of the quadrants below.

Based on Morrison and Wonnacott (2009) in Wonnacott (2014).

-

This category provides the strongest factual evidence for analysis and decision-making.

-

For something to go into the ‘evidence’ category, it needs to be proven and verified. For example: information that comes from more than one source or is a known.

-

Guidance and responsibilities set out in legislation and knowledge from research would be included here.

This relates to information that:

-

Is not properly understood.

-

Is only hearsay.

-

Has more than one meaning dependant on context.

-

Is hinted at by others but not clarified or owned.

This is information that comes to light when practitioners reflect on:

-

practice wisdom

-

emotions

-

values

-

gut instinct

-

hunches etc.

Care needs to be taken to explore whether any prejudices or areas of bias are influencing information in this quadrant.

This relates to gaps in what is known. This includes identifying:

-

What information is missing.

-

The impact of this on decision-making.

-

How gaps might be addressed.

Working through the four quadrants in the discrepancy matrix helps practitioners to:

-

Understand if there are any flaws in their thinking or in the information that they have gathered.

-

Consider how ambiguous, assumption-led, or missing information might move into the strong evidence quadrant.

The aim is to move towards developing firm ground intelligence to inform decision-making.

Briefly jot down all the different kinds of information that you discuss.

-

Invite the practitioner to briefly talk about the issues or challenges they are facing. Don’t interrupt - just let them talk for five minutes or so at this stage.

Make notes of any questions you may have so that you can return to these later.

-

Then spend time talking in more depth about the different kinds of information that the practitioner is drawing on to understand where:

-

-

There is strong evidence.

-

Assumptions are being made.

-

Information is contested or missing.

-

Briefly jot down all the different kinds of information that you discuss.

-

Then, using the list you have just developed, jointly decide where on the discrepancy matrix each piece of information should be placed.

-

When you have finished, ask the practitioner to reflect on:

-

-

What they have learnt from doing this structured reflection.

-

What they still need to know.

-

What they think they should do next.

-

![]() Wonnacott's discrepancy matrix - A valuable tool supporting practitioners with their critical thinking around different kinds of information.

Wonnacott's discrepancy matrix - A valuable tool supporting practitioners with their critical thinking around different kinds of information.

3. Safe uncertainty

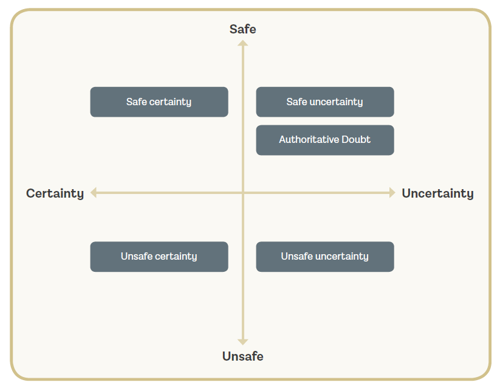

The idea of ‘safe uncertainty’ is widely used in systemic practice. It was first developed to help social workers think about how they can balance risk and safety in their work (Mason, 1993, 2019). This tool helps practitioners to explore how risk and safety are balanced when working with people who draw on care and support. It can be used in any practice context.

The model is called safe uncertainty because this is where practitioners are aiming to be. You will see from the image that the model is made up of four parts. This can seem a little confusing at first, but it is easy to understand when it is explained.

(A large view of the safe uncertainty model can be viewed in the downloadable tool below, Safe uncertainty).

Safe uncertainty

This is the quadrant we want to support practitioners to be in.

-

Being able to tolerate doubt and uncertainty and remain curious.

-

Using professional expertise to try and bring about change. Accepting that this may not be possible and that there will always be risk.

-

Practitioners who are able to work in this way are described by Mason as having ‘authoritative doubt.’

Safe certainty

-

Feeling that the risks are too high in a situation and responding by taking action to remove the risks and promote safety.

-

This safety is important but usually temporary.

Unsafe certainty

- Jumping to conclusions too quickly about what the problem (and risks are) and how this can be solved.

Unsafe uncertainty

-

Being overwhelmed by the level of risk and unsure about what to do. Feeling hopeless and uncertain about how to respond.

To use this model in supervision discussions, introduce the safe uncertainty model and briefly explain each quadrant.

Then invite the practitioner to:

-

Explore how they and other professionals respond to and manage risk (and safety) in relation to a piece of work they are involved in.

-

Be curious about which quadrant they are currently in or are more drawn to.

-

Consider what needs to change to move to a position of safe uncertainty and what that might feel like.

-

Reflect on how it feels to be closer to uncertainty than certainty when managing risk.

Focusing on safe uncertainty in supervision helps practitioners to be curious and explore new ideas about practice. This opens up possibilities for different outcomes and ways of working.

It can also help support practitioners’ well-being and resilience.

-

Being given a message that not everything is knowable, and not all harm can be prevented can help practitioners feel more contained and able to manage the pressures of working with risk.

![]() Safe uncertainty - A useful tool containing further information to support supervision discussions. (Adapted from Guthrie (2020) and Williams (2019).

Safe uncertainty - A useful tool containing further information to support supervision discussions. (Adapted from Guthrie (2020) and Williams (2019).

Using questions strategically in supervision

Over time supervisors sometimes forget or lose their ability to ask questions that facilitate reflective and critical thinking.

(Grant and Kinman, 2020)

-

This is understandable in busy and challenging work contexts where there can be pressure to focus on organisational priorities and the management function of supervision (In-Trac, 2019).

-

It can also happen when practice supervisors provide a lot of supervision sessions. Where this is the case, they may develop a core set of questions and a preferred way of working which can start to feel a little mechanistic (Pitt et al, 2021).

It is important to be reminded, from time to time, that doing things a little differently can be helpful.

In this section we introduce you to interventive interviewing. This is a valuable tool for thinking about different approaches to asking questions in supervision.

Interventive interviewing

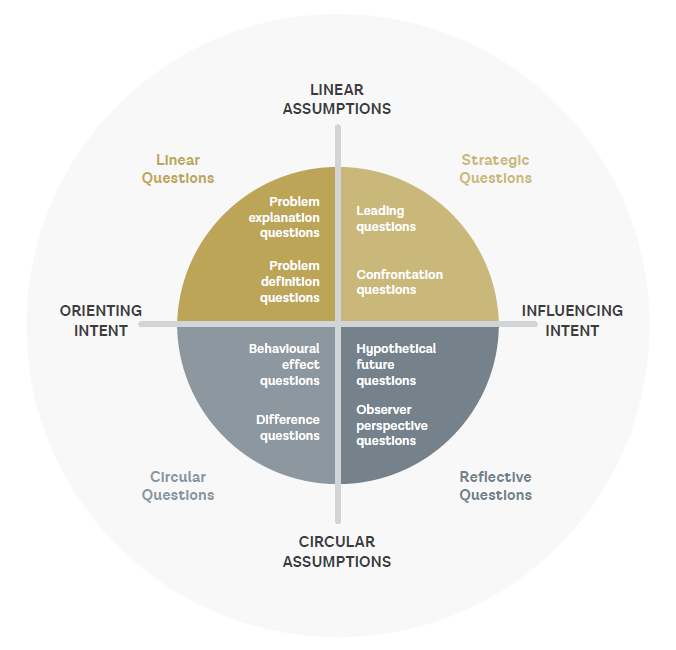

Interventive interviewing helps us think strategically about different kinds of questions we can use in supervision (Tomm, 1987a, 1987b, 1988).

The key idea behind interventive interviewing is that a well-phrased and well-judged question can help supervisees consider new perspectives and possibilities for practice. In other words, questions that you ask in supervision can help change thinking about practice.

In the following film Lydia Guthrie explains more about what interventive interviewing is.

Length: 11 minutes.

Let’s think in more detail about the kinds of questions you might ask when using interventive interviewing in supervision. If you look at the image below, you can see that two lines split a circle into four sections. Each section represents a different kind of question.

Interventive interviewing

Lineal to circular assumptions

The line that goes from the top to the bottom starts with lineal assumptions and moves to circular assumptions.

-

Lineal assumptions: means that we are working with objective facts that we can discover.

-

Circular assumptions: means that we are looking for meaning, patterns and connections to create new perspectives. There is no right or wrong answer and there are multiple possibilities to consider.

Orienting intent to influencing intent

The line that goes from the left to the right starts with an orienting intent and moves to influencing intent. These lines focus on what the person asking the questions is trying to do.

-

Orienting intent: the questioner is trying to get a better understanding of the situation and find out what is going on.

-

Influencing intent: the questioner is focusing on change and helping the other person generate different thoughts or come up with solutions for themselves.

Using interventive interviewing in supervision

Let’s now think about the four different kinds of questions that you might ask when using interventive interviewing. You can see these in the middle of the circles in the image above.

Linear questions are helpful to get an idea of what is happening. They are straightforward, fact-finding questions. They are usually asked at the start of supervision.

These questions can be:

- Problem explanation questions, asking where, when, how a problem is happening.

- Problem definition questions, trying to sort out exactly what the issue of concern.

In supervision, the supervisor might ask:

What are your:

- Biggest challenges in working with this?

What caused you to be:

- Concerned about this?

What is XXX's:

- View of their immigration status?

Circular questions (circular assumptions and orientating intent)

Circular questions are usually open questions. They track patterns, difference, and relationships and invite reflection and exploration.

These questions can be:

-

Behavioural effect questions, trying to find out how a problem affects people in a system.

-

Difference questions, exploring differences between people in a system.

In supervision, the supervisor might ask:

What impact are the Parents' arguments having on the child?

Who is most concerned about this?

When you speak to XX and they are angry with you, what do you do?

How does what is happening affect relationships between everyone?

Reflexive questions (circular assumptions, influencing intent)

Reflexive questions focus on generating new perspectives and ideas but with an intent to influence.

Reflexive questions help practitioners to stand back and take an observer perspective of themselves and their practice so that they can generate new ideas and possible solutions (Tomm, 1988, Hieker and Huffington, 2006).

These questions are often the most useful in supervision because, when asked in a facilitative way, they act as a ‘probe’ or ‘stimuli’ to think about the situation differently (Tomm, 1988).

There are lots of different kinds of reflexive questions and they can explore anything that you think is relevant to the situation. We focus here on:

-

Hypothetical future questions

-

Observer perspective questions.

In supervision, the supervisor might ask:

Hypothetical future questions

-

If you were to continue to respond to this person in the same way, what do you think would happen in three months’ time?

-

Once you catch up with all your recordings in the next three weeks, what will your next focus be?

-

Whenever I get stuck, I have to sit down and imagine how things might feel in the morning once I’ve had some distance from it. How do you get distance?

Observer perspective questions

-

Imagine that the child / parent you are working with was here now, what advice might they give you about this dilemma?

-

If your colleague were here, what would they say about that?

-

Imagine if she were here now, what do you think she would say about how this situation has affected her experience of being a mother?

You can find a complete list of reflexive questions in the interventive interviewing download available at the end of this section.

Strategic questions (linear assumptions, influencing intent)

Strategic questions often embed advice designed to influence the other person.

They are useful in challenging different perspectives and positions but should be used sparingly (and with respect for the power imbalance between you and a supervisee)

These questions can be:

-

Leading questions’ which suggest a certain line of enquiry or,

-

Confrontation questions which and challenge.

In supervision, the supervisor might ask:

-

Are you worried about the impact that a child protection plan will have on the mother's mental health?

-

Do you find it difficult to like XXX?

-

Have you considered that homophobia might be influencing the way that carers talk about this person?

-

What has stopped you so far from talking to your colleague about your conflict with them?

Adapted from Usiskin Cohen et al (2019).

![]() Interventive interviewing - A useful tool to support practitioners in supervision.

Interventive interviewing - A useful tool to support practitioners in supervision.

-

Which kinds of questions are you most drawn to?

-

Do you have default questions that you tend to rely on in supervision? Where do these fit on the interventive interviewing framework?

-

Why not pick a couple of the questions that you would not normally use and try them out in supervision to see what happens?

Final reflections - Shifting up and down the gears

Supervision offers a safe space for practitioners to:

-

Slow down and think.

-

Explore possibilities.

-

Consider how they can do their work well. (Earle et al, 2017)

This process of slowing down and reflecting is an essential foundation for critical analysis in supervision.

Practice supervisors often find the metaphor of shifting up and down the gears helpful in thinking about how they can get in the zone for these kind of discussions in supervision.

-

If you have been working at a fast pace all day, dealing with a multitude of queries, phone calls and meetings, you will have been working in fourth or fifth gear.

While this gear is helpful for dealing with a high volume of work at speed, you need to find a way of mentally coming back ‘down through the gears’ to be at the slower pace of first gear for supervision.

-

For supervision you need to be working in first gear, so that you can attend to what is being said with your full attention and all your senses.

Let’s finish by shifting the focus to thinking about how you can get in the zone to have curious and critically reflective discussions in supervision.

For example:

-

Stepping outside for five minutes to get some fresh air and be out of the office for a moment to collect your thoughts.

-

Visualising moving down through the gears whilst you wait for the kettle to boil before you go into supervision.

Please take a couple of minutes to think about:

-

Is there anything you do already that works for you and gets you in the zone for supervision?

-

Is there anything you could start doing?

Brown, L., Moore, S., and Turney, D. (2014). Analysis and Critical Thinking in Assessment. (Second edition). Research in Practice.

Brown, L., Moore, S., and Turney, D. (2014). The Anchor Principles: A 5-question guide to the stages of analytical assessment. Research in Practice.

Burnham, J. (2013). ‘Developments in Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS: visible-invisible, voiced-unvoiced’. In Krause, I. (ed) Cultural Reflexivity (2013). Karnac.

Domakin, A., and Sturt P. (2019). Using the five anchor principles in supervision. Research in Practice.

Earle, F., Fox, J., Webb, C., and Bowyer, S. (2017). Reflective supervision: Resource Pack. Research in Practice.

Fairtlough. A (2016). Professional Leadership for Social Work Practitioners and Educators, Routledge.

Grant, L. and Kinman, G. (2020). Promoting emotional resilience. Research in Practice.

Guthrie, L. (2020). Using a systemic lens in supervision. Research in Practice.

Heffron, M. C., Reynolds, D., and Talbot, B. (2016). Reflecting together: reflective functioning as a focus for deepening group supervision. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(6), 628–639.

Hieker, C. and Huffington, C. (2006). Reflexive questions in a coaching psychology context. International Coaching Psychology Review. 1(2), 47-56.

In-Trac Training and Consultancy (2019). An audit of your supervision role. Research in Practice.

Julien-Chinn, F.J., and Lietz, C. A. (2019). Building learning cultures in the child welfare workforce. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 360–365.

Mason, B. (1993). Towards positions of safe uncertainty. Human Systems, The Journal of Systemic Consultation & Management, 4 (3–4), 189–200.

Mason, B. (2019). Revisiting safe uncertainty: six perspectives for clinical practice and the assessment of risk. Journal of Family Therapy, 41(4).

Partridge, K. (2019). Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS and the LUUUTT. Research in Practice

Pitt, C., Addis, S., & Wilkins, D. (2021). What is Supervision? The Views of Child and Family Social Workers and Supervisors in England. Practice, 34(4), 307–324.

Ruch, G. (2012). Where have all the feelings gone? Developing reflective and relationship-based management in child-care social work. British Journal of Social Work, 42(7),1315–1332.

Ryde, J., Seto, L., and Goldvarg, D. (2018). Diversity and Inclusion in Supervision. The Heart of Coaching Supervision. Routledge, 71–90.

Sidebotham, P., Brandon, M., Bailey, S., Belderson, P., Garstang, J., Harrison, E., Retzer, A., & Sorensen, P. (2016). Pathways to harm, pathways to protection: a triennial analysis of serious case reviews 2011-2014. Department for Education.

Tomm, K. (1987a). Interventive interviewing: Part 1. Strategizing as a fourth guideline for a therapist. Family Process, 26(1), 13-31.

Tomm, K.(1987b). Interventive interviewing: Part 11. Reflexive questioning as a means to enable self-healing. Family Process, 26(2), 167-183.

Tomm, K. (1988). Interventive interviewing: Part 111. Intending to ask lineal, circular strategic and reflexive questions? Family Process, 27(1), 1-15.

Turney, D. (2014). Analysis and Critical Thinking in Assessment: A literature review. Research in Practice.

Usiskin Cohen, E., McNamara, H., and Williams, J. (2019). Interventive Interviewing. Research in Practice.

Williams. J. (2019). Safe Uncertainty. Research in Practice.

Wilson, K., Barron, C., Wheeler, R., and Jedrzejek, P.E.A. (2018). The importance of examining diversity in reflective supervision when working with young children and their families. Reflective Practice, 19(5), 653–665.

Wilkinson, J. (2020). Promoting evidence-informed practice in supervision. Research in Practice.

Wonnacott, J. (2014). Developing and Supporting Effective Staff Supervision. Pavilion.

Reflective supervision

Resource and tool hub for to support practice supervisors and middle leaders who are responsible for the practice of others.