Putting reflection at the heart of supervision

Part of Reflective Supervision: Learning hub > Practice Supervisor resources

Select the quick links below to explore the key sections of this area for Putting reflection at the heart of supervision.

The reflective supervision cycle Learning from research observing supervision Key principles of effective supervision Final reflections

Introduction

Many practitioners say that they would like to reflect more in supervision.

-

In some professions the identification, management and recording of risk can get in the way of supporting practitioners to reflect.

-

By asking open, exploratory questions, practice supervisors can help practitioners to reflect and draw on learning from their experiences to support decisions about what to do next.

-

The reflective supervision cycle and the seven principles of effective supervision are helpful frameworks to support reflection in supervision.

This is the second of two linked sections exploring the role and functions of supervision. You can read this standalone; however, we think you will get more out of it if you first read What is the purpose of supervision?

The content has been adapted from publications developed as part of the Practice Supervisor Development Programme (PSDP) funded by the Department for Education.

-

An audit of your supervision role by In-Trac Training and Consultancy (2019).

-

Using the supervision relationship to promote reflection by Guthrie (2020).

-

The role and functions of supervision by Maglajlić (2020).

The reflective supervision cycle

Let’s do a quick recap. In the linked What is the purpose of supervision?, we introduced the integrated model of supervision and thought about what the purpose of supervision is.

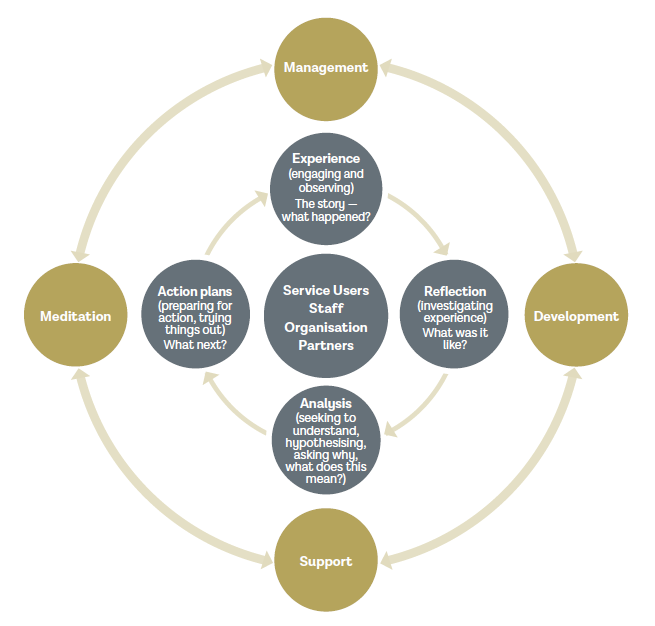

The integrated model of supervision (often referred to as the 4x4x4 model) is one of the most influential and widely used models of supervision within social care (Morrison, 2005, Wonnacott, 2014).

The model focuses our attention on three areas that are part of the supervision process:

- Role and functions of supervision - what is supervision for?

- The reflective supervision cycle – how can supervision discussions be reflective?

- Stakeholders - whose needs does supervision meet?

Each of the three areas are made up of four elements (which is why it is often called the 4x4x4 model).

The integrated model of supervision

We are now going to turn our attention to the middle layer of the integrated model of supervision and think about why reflection is so important in supervision. It is made up of four elements:

- Experience

- Reflection

- Analysis

- Action plans.

These may seem familiar to you. This is because it builds on Kolb’s highly influential theory of adult learning (1984) which you are likely to have come across. Kolb argued that adults learn by reflecting on their experiences. They can then apply this learning going forward as they encounter new experiences.

Reflections of the reflective supervision cycle

- Learning is triggered by discussing experiences (e.g. a problem that must be solved or an unfamiliar or challenging situation) at supervision.

- Exploring each stage in the cycle helps practitioners to reflect on what they have been doing and situations they have encountered in practice.

- By asking open, exploratory questions, practice supervisors can help practitioners to reflect on their work in practice and draw on learning from these experiences to support decisions about what to do next.

Adapted from In-Trac (2019)

Taking a closer look at the reflective supervision cycle

The focus here is helping your supervisee to tell the 'story' of what has happened. Alongside exploring the perspective and actions of your supervisee, this will often involve considering multiple stories, including the perspectives of:

- People who draw on care and support.

- Others in their personal and profession networks.

Questions that support accurate and detailed recall of events ensure the richest possible discussion later in the cycle.

Supervisees can be helped to recall more than they think they know when they are asked the right questions.

This is about getting in touch with the practitioner's feelings. This can bring out further information that may not yet have been consciously processed by the practitioner, and can:

- Help the practitioner make links between the current situation and prior experiences, skills and knowledge.

- Reveal underlying assumptions or attitudes that might otherwise go unvoiced. This helps you understand any personal factors in the practitioner's life that may influence their understanding of the experience.

This involves putting the information available under the microscope to help you and your supervise understand what it means. This means:

- Thinking about everyone's perspectives.

- Considering what is known and what is uncertain or ambiguous.

- Considering how research, theory and practice wisdom may help make sense of the information you have.

Using this information to test out different hypotheses that help explain what has happened or is happening.

The focus here is on translating analysis into planning, preparation and action. This includes:

- Identifying goals and outcomes.

- Identifying what success would look like and how it will be evaluated.

- Thinking about what practice skills are needed to engage and collaborate with the individual, family and wider network that your supervisee is working with

- Exploring any anticipated challenges or complications.

- Discussing what to do if things do not go to plan.

Adapted from In-Trac (2019)

Questions around the reflective supervision cycle

The reflective supervision cycle can support practice supervisors to think about the questions they want to ask in supervision, how they ask them, and how these questions can support reflection.

Example questions are provided below on the four main areas of focus.

As you read the questions notice which ones:

-

You ask supervisees regularly.

-

You ask only occasionally.

-

That you have never asked.

-

You find it hard to imagine asking.

-

What was your aim? What planning did you do?

-

What happened leading up to this?

-

What did you expect to happen?

-

What reactions did you notice to what you said and did?

-

What were the key moments that stood out to you?

-

What surprised or puzzled you?

-

Did you do anything differently from what you had planned? What changes or choices did you make?

-

If anyone else was there, what did they think about what happened?

-

What did you say and do?

-

What do other professionals think?

-

What feelings did you bring with you on the day?

-

What is your gut feeling about what happened?

-

Can you describe the range of feelings you had at the time?

-

What did the incident / event / interview / visit / your feelings / this person remind you of?

-

What previous work, processes, skills, knowledge are relevant here?

-

Have you encountered anything similar?

-

What assumptions might you be making? How might differences or similarities between you and other people influence this?

-

Does this situation challenge you in any way? Why?

-

When did you feel most or least comfortable?

-

What was left unfinished?

-

How do you think people who draw on care and support feel about what happened? What do they want to happen now?

-

How do you explain or understand what happened?

-

How does this confirm or challenge your previous understanding or explanations about the situation?

-

What new information emerged?

-

What might help you make sense of what happened? (e.g. knowledge, theory, training, research, policy, or values)

-

How else might you have managed this?

-

What needs, risks or strengths do you see in this situation?

-

What is unknown?

-

What conclusions are you drawing from this?

-

What would this organisation want us to do?

-

Based on our discussion, can you summarise where things are at, and what needs to be done next?

-

What information needs to be obtained from others now?

-

What are your aims in the next phase of work?

-

What is urgent and essential?

-

What would be desirable?

-

How can we ensure that we collaborate with people who draw on care and support?

-

What would be a successful outcome from the perspective of people who draw on care and support / other key agencies?

-

What are the possible best or worst responses from everyone involved?

-

What contingency plans do you need? What is the bottom line? Where do you feel confident?

-

How can you prepare for the next step?

Having read the questions, take a moment to pause and think about what this has shown you about:

- What kind of questions you routinely ask in supervision.

- Which parts of the reflective supervision cycle you usually focus on.

It is important to highlight that the reflective supervision cycle can be used flexibly and adapted to your needs:

- If you don’t have much time, try asking a few questions from each part of the reflective supervision cycle to see how your supervisee responds.

- Or you could use this to have a much longer detailed discussion or debrief during a supervision session.

Challenge yourself to do something differently

Pick three questions that you find hard to imagine yourself asking. Over the next few weeks ask each question at least once in supervision and notice what your supervisee says in response.

Adapted from In-Trac (2019)

![]() Questions around the reflective supervision cycle - Use this tool to refer to during supervision discussions.

Questions around the reflective supervision cycle - Use this tool to refer to during supervision discussions.

1. Wilkins et al. (2017) recorded supervision sessions in child and family social work. Most followed the same structure:

Problem identification

The practitioner begins by giving an extensive update about a family’s current situation.

This was described as a ‘verbal deluge’ because of the amount of information shared, often at a rapid pace.

Providing a solution

Immediately after the update, the practice supervisor provides advice and instructions about what to do next. This usually involved identifying tasks for the practitioner to do.

In many recordings, practice supervisors were typing and taking notes throughout.

2. In a second study, practice supervisors were recorded responding to a simulation of a newly qualified social worker seeking guidance (Wilkins and Jones, 2018). Analysis of the recordings found that:

- Practice supervisors often acted as expert problem-solvers - asking closed questions and giving instructions, rather than supporting the social worker to consider alternative ideas and possibilities.

- Discussions are often focused on:

- What needed to be done.

- When by.

rather than:

- Why a course of action needed to take place.

- How conversations with people who draw on care and support might be approached.

Adapted from Guthrie (2020) and Maglajlić (2020)

Bypassing reflection in supervision

There are a couple of points to highlight here:

- Moving straight from problem identification to providing a solution means there is no room to reflect on the issues together, discuss alternative ideas, or to explore other concerns or strengths.

- It also means that the four elements of thinking and reflecting about practice in the integrated model of supervision are bypassed.

Supervision with reflection squeezed out

Practice supervisors in both studies needed to manage risk, progress work with children and families and meet organisational requirements for recording. This function of supervision was taking priority.

- The problem is that when the management function dominates in this way, this leaves little or no room for the other functions of supervision (In-Trac, 2019).

- When this happens, reflection can be squeezed out.

Key principles of effective supervision

Wilkins (2019) highlights that during his research, he encountered many examples of practice supervisors providing helpful and reflective supervision in child and family social work. Having explored this further, he proposed seven principles that need to be in place for effective supervision:

When supervision discussions are effective, practice supervisors are working skillfully in seven key areas.

(Wilkins, 2023).

Bostock and Kinman (forthcoming) reviewed learning from several research studies of supervision. They argue that when supervision is effective practice supervisors are working skilfully in six key areas (which they call domains).

Both research studies provide a helpful framework for practice supervisors to use in supervision discussions. We have drawn the following key points that are consistent across both studies.

For supervision to be effective it needs focus on:

- the views and ideas of people who draw on care and support

- needs, risk, harm and strengths

- rights and equity-based practice

and need to provide space for:

- curiosity and exploring multiple perspectives

- emotional reflection and wellbeing

- planning for the how’s and whys of practice.

Don’t forget that you need to work collaboratively with supervisees for them to get the most out of these discussions.

We recommend talking to your supervisees if you start to use these principles in supervision, so that they understand what you are doing differently and why. It is also useful to seek feedback from them about how supervision changes as a result.

![]() The seven principles of effective supervision - Use this information to refer to during supervision discussions.

The seven principles of effective supervision - Use this information to refer to during supervision discussions.

Reflective questions

-

What do you think about these principles?

-

Do you already use any of them in supervision?

-

Are there any principles you want to start using?

Don’t forget that you need to work collaboratively with supervisees for them to get the most out of these discussions.

We recommend talking to your supervisees if you start to use these principles in supervision, so that they understand what you are doing differently and why. It is also useful to seek feedback from them about how supervision changes as a result.

Final reflections

This section has focused on how to put reflection at the heart of supervision. Before moving on to the next section take a moment to think about:

- What struck you most as you read the information in this section.

- Then ask yourself - what will you stop, start and continue doing in supervision to support reflective conversations about practice?

Bostock, L. and Grant, L. (forthcoming). Supervision Tool Assessing Reflexivity (STAR) Research in Practice.

Collins-Camargo, C., and Millar, K. (2010). The potential for a more clinical approach to child welfare supervision to promote practice and case outcomes: A qualitative study in four states. The Clinical Supervisor, 29(2), 164–187.

Department for Education (2023). Children’s social care national framework.

Earle, F., Fox, J., Webb, C., and Bowyer, S. (2017). Reflective supervision: Resource Pack. Research in Practice.

In-Trac Training and Consultancy (2019). An audit of your supervision. Research in Practice

Maglajlić, R. (2020). The role and functions of supervision. Research in Practice.

Pitt, C., Addis, S., and Wilkins, D. (2022). What is supervision? The views of child and family social workers and supervisors in England. Practice, 3(4), 307-324.

Webb, C. (2021). Using Participatory Action Research to Develop a Resource for use in Reflective Supervision in Child and Family Social Work. Unpublished thesis: University of Bristol.

Wilkins, D., Forrester, D., and Grant, L. (2017). What happens in child and family social work supervision? Child and Family Social Work, 22(2), 942–95.

Wilkins, D., and Jones, R. (2018). Simulating supervision: How do managers respond to a crisis?, European Journal of Social Work, 21(3), 454-466.

Wilkins, D. (2019). A 3D model – forms of support for social workers. Research in Practice.

Wilkins, D. (2023). Seven Principles of Effective Supervision for Child and Family Social Work. Practice, 36(3), 213–229.

Reflective supervision

Resource and tool hub for to support practice supervisors and middle leaders who are responsible for the practice of others.