Emotional resilience and containment

Part of Reflective Supervision Hub > Practice Supervisor resources

Select the quick links below to explore the key sections of this area for Emotional resilience and containment:

What is emotional resilience How can emotional resilience be developed Containing difficult emotions Providing holistic containment

Building a team culture of resilience Final reflections

Introduction

Building and sustaining resilience is an important part of practitioner wellbeing. This is because resilience acts as a buffer against the negative impact of stress and emotional demands at work.

Supervision should support practitioners to reflect on the emotional impact of practice and provide an opportunity to model and develop learnable skills of resilience. A team culture where people feel connected to colleagues promotes resilience. As practice supervisor, you play a key role in creating a supportive team culture where practitioners can share when they’re feeling less resilient and seek support without fear of judgement or blame.

Resilience should not be the sole responsibility of individual practitioners. It is the responsibility of the whole organisation. This chapter explores emotional resilience and containment. The content within this chapter has been adapted from publications developed as part of the Practice Supervisor Development Programme (PSDP) funded by the Department for Education.

-

Team as secure base model by Biggart (2019)

-

The holistic containment wheel by Fairtlough (2019)

-

Promoting emotional resilience by Grant and Kinman (2020)

-

Containing difficult emotions in supervision by Sturt (2019)

-

Promoting emotional resilience in online and hybrid spaces by Sturt (2022).

-

When we are resilient, we can respond to a challenge, setback, or stressor by drawing on a wide range of resources and capacities:

-

personal

-

psychological

-

professional.

-

If adversity is managed successfully, we gain strength from this experience and our resilience-building skills increase.

Adapted from Grant and Kinman (2020)

Working in caring roles can be stressful, so building and sustaining resilience is an important part of practitioner wellbeing.

(Sturt, 2022)

There is a growing body of research that suggests emotional resilience acts as a buffer against the negative impact of stress and emotional demands at work.

- This helps practitioners to keep going in adverse situations.

- When practitioners navigate difficult situations, job satisfaction, engagement and retention increase.

It is important to remember that personal resilience is only one element of resilience.

Resilience should not be the sole responsibility of individual practitioners. It is the responsibility of the whole organisation.

This means:

- Building a supportive culture that promotes resilience at all levels in an organisation.

- Taking action to address any organisational issues which add to pressures experienced by practitioners.

Adapted from Grant and Kinman (2020)

There are several qualities which are positively associated with emotional resilience. Click on each one to find out more.

- Self-awareness

-

- Being able to think about the impact of situations on oneself and others.

- Having a strong sense of personal identity developed through reflection.

- Confidence and self-efficacy

- Believing you have the skills and ability to achieve a goal or work through adverse experiences.

- Self-motivation.

- Emotional literacy

- Understanding one’s own and other people’s emotional reactions and how these can influence behaviour.

- Autonomy, purposefulness, and persistence

- Having a sense of purpose and an understanding of what action needs to be taken (both short- and long-term priorities).

- Able to recover from obstacles and continue working towards goals.

- Social support

- Drawing on a strong network of supportive relationships during challenging times (both personally and professionally).

- Relating well to other people and making connections.

- Adaptability, resourcefulness, and effective problem-solving skills

- Responding to challenges positively and flexibly.

- Drawing on different perspectives to generate ideas and solutions.

- Adapting to change and learning from the experience.

- Enthusiasm, optimism, and hope

- Having a positive but realistic outlook.

- Thinking that positive change will usually happen.

Lastly, whilst not a quality of resilience in itself, it is important to highlight that resilient practitioners prioritise self-care.

-

This means that they actively take steps to protect their wellbeing when they are feeling less resilient.

-

They also maintain healthy boundaries between work and personal life.

Adapted from Grant and Kinman (2020)

What does it mean?

-

Monitoring and regulating emotional reactions to practice.

-

Being aware of the impact of emotions on decision-making.

Why is this important?

-

Being able to manage emotional reactions in oneself and others is a powerful component of resilience.

-

During stressful situations, we often simply react rather than process thoughts and emotions accurately.

-

Learning to attend to our emotions and be aware of their impact is crucial for emotion regulation.

How can it be enhanced?

-

Emotional writing: making notes on our emotional experiences can be an effective way of gaining insight into how they affect us.

-

Doing this for a couple of minutes a day has benefits for mental health.

-Tip- You could encourage practitioners to do this as part of their preparation for supervision.

What does this mean?

-

Practicing self-kindness and being tolerant of your own vulnerabilities and imperfections.

-

Acknowledging your strengths as well as your weaknesses.

-

Accepting that sometimes things go wrong, and this is normal.

Why is this important?

-

Self-compassion can improve coping abilities and reduce the risk of burnout.

-

It also underpins positive attitudes towards self-care and healthy coping behaviours.

How can it be enhanced?

-

Challenging yourself to think differently about a situation can encourage more positive self-talk, and challenge faulty thinking patterns and negative self-talk.

-Tip- Discuss self-compassion and practical self-care strategies with your supervisees in supervision and as a group.

What does this mean?

-

Having a wide range of coping strategies (both problem-focused and emotion-focused).

-

Selecting appropriate strategies to use in different situations.

Why is this important?

-

Resilient people are adaptable and flexible.

-

They use emotion-focused coping (which aims to change their negative feelings about stressful situations).

-

They also use problem-focused coping (which tackles the problem at source).

How can it be enhanced?

-

Optimistic thinking, trying to see an event in a positive light, can be a powerful way to transform thinking.

-

Confronting, naming, and reframing a stressful situation can also be effective.

-Tip- Ask supervisees to reflect on the following questions:

-

What skills do I have to manage this situation?

-

What has helped in the past?

-

Who can I ask who has experienced something like this before?

-Tip- Encourage practitioners to talk about their own support needs and how best to support each other in supervision and as a group.

What does this mean?

-

Reflecting on actions, decision-making and emotional reactions to practice.

-

Communicating self-reflections with others and changing approaches to practice because of this.

Why is this important?

-

Reflective ability is a key protective resource for practitioners.

-

Being able to reflect on thoughts, feelings and behaviours helps practitioners be more emotionally resilient and experience better mental health.

How can it be enhanced?

-

Keeping a reflective diary to explore emotional reactions in practice (positive and negative) can be helpful.

-Tip- Encourage practitioners to reflect on emotional responses to practice and be open to feedback about this in supervision.

-Tip- Ask supervisees to reflect on successes (no matter how small). For example:

-

When did you last feel your best self at work?

-

What skills did you demonstrate and how could you use those skills to overcome future challenges?

What does this mean?

- Setting clear boundaries between work and personal life provides opportunities to recover both mentally and physically from being at work.

Why is this important?

-

A healthy work-life balance is crucial for building resilience.

-

Knowing how to switch off from work and allowing yourself the space and time to do this protects mental and physical health and job performance.

How can it be enhanced?

-

Promote healthy use of technology. It is easy to become addicted to technology; constantly checking emails can become habitual. This can raise anxiety and stress levels.

-

Use an everyday activity at the end of the day, such as making a cup of tea, as a buffer between work and home.

-

While the kettle is boiling, and the tea is brewing, note down any ‘to do’s’ for tomorrow. You can email them to yourself if it helps. Then drink the tea, let go of the day and begin to focus on home.

-Tip- Highlight the importance of ‘switching off’ and encourage practitioners to share effective strategies in supervision and as a group.

Adapted from Grant and Kinman (2020)

![]() Professional Wellbeing Self-Assessment Tool - This tool supports practitioners to reflect on their professional wellbeing. This can be completed individually and then discussed in supervision.

Professional Wellbeing Self-Assessment Tool - This tool supports practitioners to reflect on their professional wellbeing. This can be completed individually and then discussed in supervision.

![]() What motivates your team members to keep going? This tool helps you to learn more about why practitioners stay in their jobs, what they value about their works and what motivates them to stay.

What motivates your team members to keep going? This tool helps you to learn more about why practitioners stay in their jobs, what they value about their works and what motivates them to stay.

-

What resilience qualities do your supervisees have? How can you find out more?

-

How can you support supervisees to identify areas for development and set achievable goals in relation to their wellbeing and resilience?

Adapted from Grant and Kinman (2020)

Containing difficult emotions in supervision

It is important to support practitioners to process emotional responses arising from their work because:

- Building and sustaining relationships with people who are in crisis or severe distress can be challenging.

- Close involvement with pain, loss and grief can evoke strong emotions (particularly if this echoes experiences in practitioners’ own lives (Patterson, 2020).

- Being exposed to other people’s trauma can be difficult to deal with. This is known as vicarious or secondary traumatisation.

Practitioners need space and time in supervision to get in touch with these feelings, acknowledge their impact and ensure they do not affect their work.

Supporting practitioners to identify, name and reflect on emotional responses to their work is referred to as containment.

- Being contained in supervision can help practitioners make sense of challenging feelings arising from their work.

- It is important to process these feelings rather than suppress them (Patterson, 2020).

Containment

The concept of containment was first developed by Bion (1962).

Bion argued that all of us feel uncontained some of the time. When we do, we need the help of another person (the container) to settle ourselves. When we act as a container, we are emotionally receptive and attuned to another person’s troubled, turbulent and anxious feelings or states of mind. We help the other person think more clearly about their experiences and responses to them.

You can see containment in action in this film which shows a practice supervisor responding to a supervisee who is struggling in supervision.

Where practitioners are not contained, they may become overwhelmed by the information they are receiving, and not be able to communicate effectively with people who draw on care and support.

This is illustrated in this graphic adapted from Sturt (2019).

When a person is overwhelmed, this can affect their capacity to communicate with and listen to people who draw on care and support.

Where practitioners feel contained, this helps them to:

- Receive and understand information.

- Be sensitive and receptive to another person's cues.

Sometimes, supervisees may not be aware of the strength of their feelings and responses to practice.

They may also feel ashamed or find it difficult to talk about what they are feeling.

- These discussions require skill and focus on your part.

- They also work best within a safe and trusting supervision relationship which allows your supervisee to take risks and be open with you.

This quote from Patterson (2019, p. 47) illustrates these points.

‘At its best professional supervision provides a safe space where feelings stirred up by close and sustained involvement in this kind of work can be given expression so that practitioners retain the ability to feel empathy; to see, to hear and to think clearly’.

-

How would you notice if a supervisee might be becoming overwhelmed or feeling uncontained?

-

How do you create space for supervisees to express difficult feelings in supervision?

So far, we have thought about the role of containment in helping practitioners process their emotional responses to practice. This is only part of the story. It is helpful to also think about containment more broadly using the idea of holistic containment.

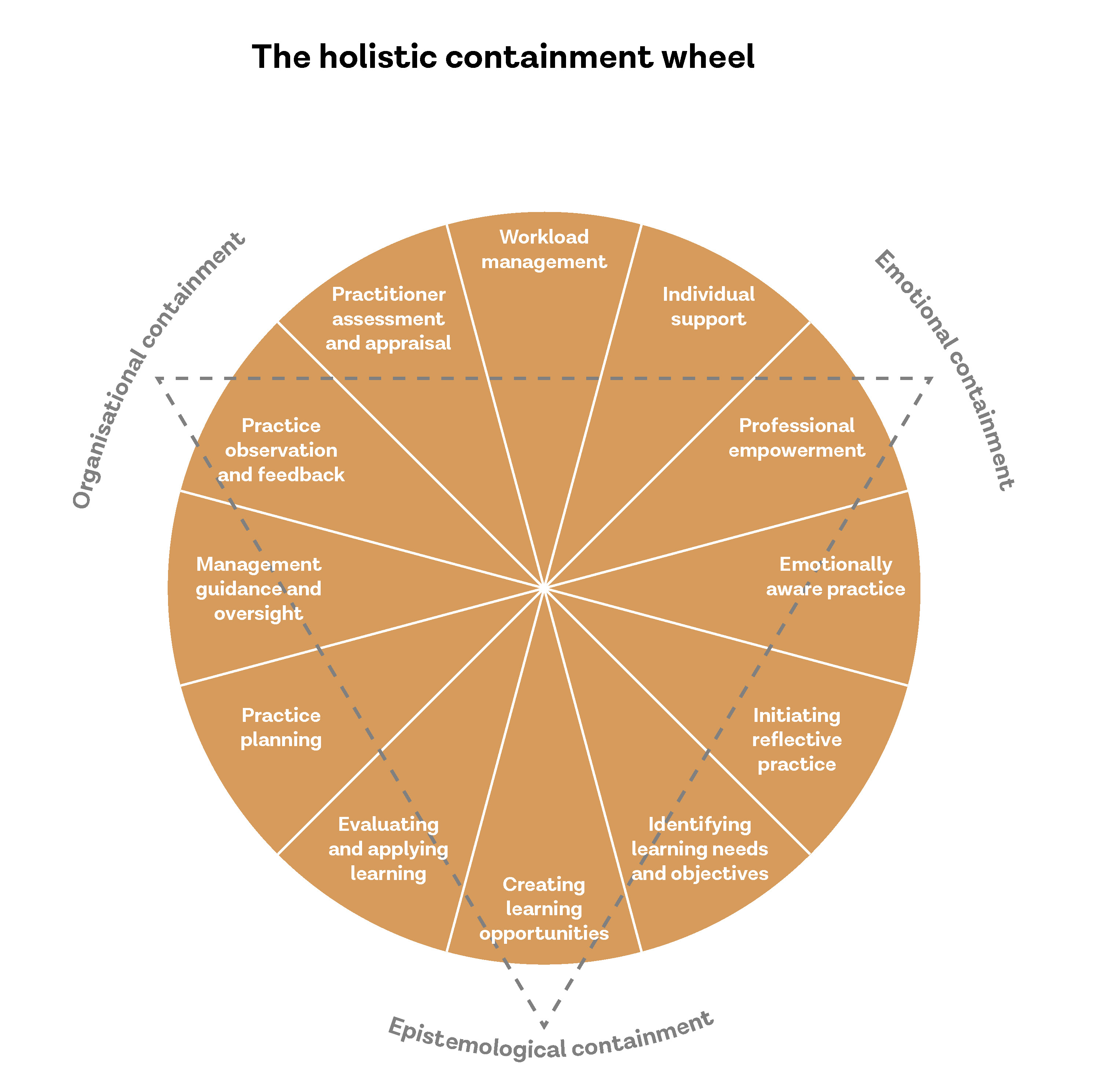

Holistic containment was developed by Ruch (2002), who argued that three kinds of containment are needed for practitioners to thrive. You can see these at the outer edge of the wheel in the diagram below.

If you look at the inside of the wheel, you can see that each kind of containment is broken down further into elements (developed by Fairtlough, 2017).

Organisational containment – support systems for employees, appraisals, practice observations, supervision processes and policies.

Emotional containment - support, supervision and a safe space provided by the practice supervisor.

Epistemological containment – support for learning, knowledge, skill development and CPD.

The holistic containment wheel

![]() Holistic containment wheel - This tool provides more detailed information and prompts you to consider how you can work effectively in all three areas to support practitioners.

Holistic containment wheel - This tool provides more detailed information and prompts you to consider how you can work effectively in all three areas to support practitioners.

Practice observations and feedback

One of the elements of the holistic containment wheel that can easily be overlooked is practice observation. There are many benefits to regularly observing supervisees in practice.

- Observations show you exactly how a practitioner communicates in practice. This allows you to consider the quality of their practice skills and provide feedback.

- Preparing for an observation with your supervisee, and reflecting on this jointly afterwards, gives you a clear picture of their strengths and areas for development. This can be a highly supportive and motivating process.

We have developed two tools to support observations of social work practitioners in children and families and adults social work settings. Most of the content will be useful to practice supervisors working in other settings also.

Each tool provides:

- A summary of research findings to inform your thinking about practice observations.

- A template (based on these findings) to guide your feedback when observing practice observing practice.

- Points to consider when preparing for observations.

Building a team culture of resilience

Positive team relationships with peers and practice supervisors also play a key role in helping practitioners to be resilient (Cook, 2024). This means that you should actively support the development of a culture of resilience within your team.

Let’s start by thinking about how people in resilient teams behave to each other. A resilient team refers to a team culture in which practitioners:

-

Openly discuss their strengths and concerns.

-

Feel empowered to share emotionally distressing experiences.

-

Have a strong sense of group identity, looking out for each other and providing support when needed.

Remember: a resilient team is more than a group of individually resilient people.

Adapted from Grant and Kinman (2020)

When building a team culture of resilience, it is important to focus on five areas:

Build trust, where everyone can:

-

Ask for help, admit to mistakes, and disagree with each other.

-

Share collective learning from mistakes and successes.

Build commitment, where everyone can:

-

Share their ideas.

-

Receive praise and praise others when things go well.

Build a culture of shared responsibilities, where everyone can:

-

Consider how problems can be shared and resolved.

-

Be autonomous and make decisions whenever they can.

Build a team that recognises individual strengths, where everyone:

-

Knows what each other’s strengths and skills are and can draw on these when needed.

Build an inclusive team that celebrates diversity, where everyone:

-

Has a voice and is valued equally.

-

Understands the impact of racism, discrimination, exclusion, and stereotyping (on both their colleagues and on people who draw on care and support).

The team as a secure base model

The team as secure base model can be used to support the development of team resilience.

The idea of the secure base comes from attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969). When we have a secure base, we have people we can turn to, when life is stressful, who are:

- available

- sensitive to our needs

- reliable.

In emotionally demanding work contexts, practice supervisors and team members often provide a work-related secure base for each other.

The team as secure base model consists of five domains:

- availability

- sensitivity

- acceptance

- cooperation,

- team membership.

A download of the Secure base model is available below.

You can explore how to support your team to become more resilient in this area by using the secure base model.

Have a look at the information and think about how you can use this to support your team to develop a secure base.

![]() Secure base model

Secure base model

This is a useful exercise and worth spending time over.

- If you don't have enough time now, you could spend a few minutes exploring one domain and come back to the rest at another point.

- You can also download this model to print or save for later.

It is also helpful to share this with your team, and discuss each of the domains and the prompt questions together to kickstart thinking about how you can become a team with a secure base.

Building a culture of resilience with online and hybrid team

It is now common for many practitioners to work remotely or in a hybrid way.

This has had a significant impact on communication within and between teams (Cook et al., 2020).

It has also made it more challenging to support employees’ mental health and wellbeing (Fernand, 2024).

This means that it is important to think about what practice supervisors need to do differently to build resilience in order to support and manage on online or hybrid team.

![]() Team as a secure base model in online and hybrid spaces - This tool provides detailed information about how you can support teams who work remotely to build culture of resilience

Team as a secure base model in online and hybrid spaces - This tool provides detailed information about how you can support teams who work remotely to build culture of resilience

Final reflections

Who contains the container?

As practice supervisor, you play a key role in creating a team culture that supports practitioners to share when they’re feeling less resilient and to seek support without fear of judgement or blame.

Adapted from Sturt (2022)

It is also important to remember that your own resilience can dip and sometimes you will need containment too. This is true for everyone regardless of their level of skill or experience.

- Supervisees need a calm, reflective space to explore their practice.

- To support your own wellbeing and maintain your resilience, you need your own reflective space.

- If you don’t have this, it makes it harder for you to be in the right state of mind to offer this to practitioners.

Unfortunately, in many social care organisations the support needs of practice supervisors can be overlooked (Patterson, 2020). Practice supervisors may then attach less importance to looking after themselves (Toasland, 2007).

So the question is: If you are a container offering emotionally containing supervision, who is containing you? Containers need containing!

-

What do you need to do to ensure you are supported to provide containment?

-

How can your line manager, peers and others in your organisation contain you as a practice supervisor?

-

What conversations would you like to have about this in your organisation?

Adapted from Sturt (2019) and Grant and Kinman (2020)

Biggart, L. (2019). Team as secure base model. Research in Practice.

Bion, W. (1962). Learning from Experience. Karnac Books.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Volume 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

Cook, L.L., Zschomler, D., Biggart, L., and Carder, S. (2020). The team as a secure base revisited: remote working and resilience among child and family social workers during COVID-19. Journal of Children’s Services, 15(4), 259-266.

Cook, L. (2024) Strengthening the workforce: Retention in social work. Research in Practice.

Fairtlough, A. (2017). Professional leadership for social work practitioners and educators. Routledge.

Fairtlough, A. (2019). The holistic containment wheel. Research in Practice.

Fernand, L. (2024). How to build a supportive hybrid work environment. Red Cross.

Grant, L., and Kinman, G. (2013). Bouncing back? Personal representations of resilience in trainee and experienced social workers. Practice, 25(5), 349-366.

Grant, L., and Kinman, G. (2020). Promoting emotional resilience. Research in Practice.

Patterson, F. (2019). Supervising the supervisors: What support do first-line supervisors need to be more effective in their supervisory role? Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 31(3), 46–57.

Patterson, F. (2020). Meeting the supervisory needs of practice supervisors. Research in Practice.

Ruch, G. (2002). From triangle to spiral: Reflective practice in social work education, practice and research. Social Work Education, 21(2),199-216.

Sturt, P. (2019). Containing difficult emotions in supervision. Research in Practice.

Sturt, P. (2022). Promoting emotional resilience in online and hybrid spaces. Research in Practice.

Toasland, J. (2007). Containing the container: An exploration of the containing role of management in a social work context. Journal of Social Work Practice, 21(2), 197-202.

Reflective supervision

Resource and tool hub for to support practice supervisors and middle leaders who are responsible for the practice of others.