Good work should be available for all, yet we are still far from that reality.

The employment inequality gap for disabled people and people with long term health conditions in the UK is particularly poor. Disabled people have an employment rate that is 28.8% percentage points lower than that of people who are not disabled, and people with five or more health conditions have an employment rate of just 23%.

But while this is a national challenge that requires a stronger impetus by central government to spur a change in attitudes and employment practices, there is much that can still be done locally. The need has long been recognised here in Camden. Only 4.4% of people with learning disabilities are in paid employment compared to the London average of 7%, and only 6% of adults in contact with secondary mental health services are employed compared to 7% in London and 9% nationally.

We know this is a complex area with few quick fixes; these are deep-rooted systemic issues in the labour market. But if we want to effectively enact change for the longer-term, we know it needs to begin with the people affected – disabled residents with experience of being locked out of work. It’s their, often unheard, stories that matter most – and it’s their ideas for change that will give us the best chance of making a lasting difference.

It’s why in 2021, the Inclusive Economy and Adult Social Care teams at Camden Council – in partnership with Camden Disability Action (CDA), a disability rights charity that works to promote the equality of disabled and d/Deaf people living or working in Camden – began a co-design project with the vision of designing a new service led by the needs and lived experience of residents.

Our approach is rooted in the social model of disability, a way of viewing the world which says people are disabled by the society they live in – that disadvantage is not a biological inevitably. We assembled a diversity of stakeholders at the council and engaged with our ecosystem of community partners to work in a multidisciplinary way. All the while ensuring that any new service builds on the development of Good Work Camden, Camden Council’s innovative approach to employment support.

The process began, as every good human-centred design methodology should, with user-led research. It’s about really listening to the people who will ultimately be impacted by a new service, to gain a holistic understanding of their experiences and aspirations. Over a number of months, CDA trained a diverse group of disabled people to become community reporters and gather stories and perspectives from other disabled residents, as well as employers and employment support providers.

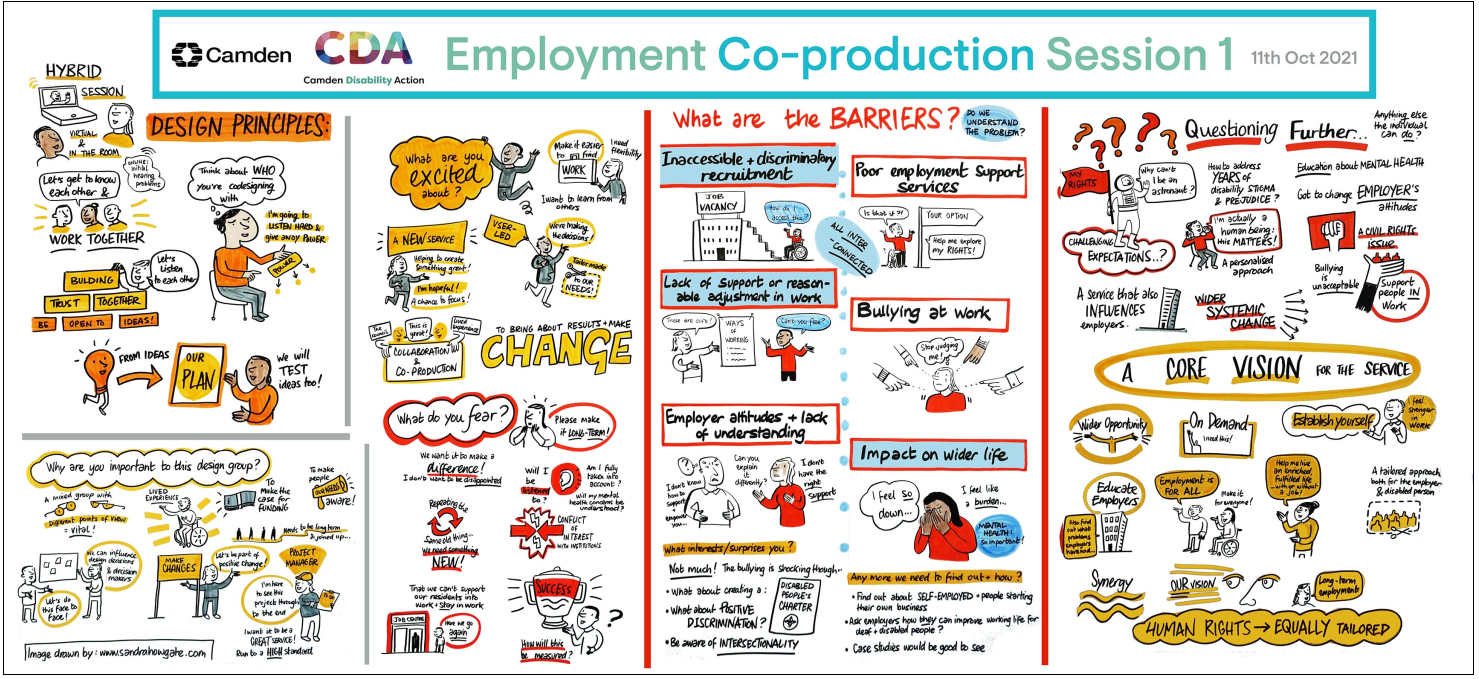

These experiences tell the often difficult, but essential, employment stories of exclusion, discrimination and even abuse. They then formed the grounding for our co-design workshops with disabled residents and council officers in autumn of this year. First, we examined the many barriers that residents currently face – from inaccessible and discriminatory recruitment, bullying at work and archaic employer attitudes, to poor quality employment support services and the impact it had on people’s wider life and mental health.

An illustration from one of the co-design workshops depicting the hopes and aspirations for the project.

These barriers then fed into a process of idea generation and scrutiny. An iterative approach that examined proposed interventions, such as creating opportunities for paid work for disabled people as employment advisors, trainers and mentors, and the need for named advisors with a strong rights-based knowledge and approach. Ideas focused on engagement with employers, to shift attitudes and encourage a variety of job vacancies and recruitment routes. Other ideas looked at engagement with schools and colleges (such as rights based training for young people), as well as the need for policy work to challenge wider barriers such as improving awareness of Access to Work.

All of these areas were then considered through the perspective of people accessing our services. We looked at how a service could be distinct from current provision, who our change partners are (such as unions, disabled employee networks and business forums) and how we will communicate with them.

In 2022, our focus will begin to shift from design to delivery. We will start to pilot and test potential service blueprints for each element of the service, ensuring disabled people are embedded in the service and that we build on existing provision. We also want to work with a small group of employers and education providers to better understand needs and issues before considering how to approach delivery.

There is much still to do, but we are hopeful. Being led by residents has given us confidence in the process and our capacity to make a difference at a local level.

Because ultimately, if good work should be an option for all, we can all play a part in making it so.